At the Frankfurt Marathon last October, a 59-year-old Irishman named Tommy Hughes threw down a stunning 2:27:52. The time was a single-age world record—and when Hughes’s 34-year-old son Eoin crossed the line a few minutes later, in 2:31:30, earned them a spot in the Guinness World Records book for fastest father-son duo.

Their performances also got them into the Journal of Applied Physiology, which last month published the results of a series of physiological tests on them by a research team led by Romuald Lepers of the University of Bourgogne Franche-Comté in France, working with colleagues at the University of Toulon and Liverpool John Moores University in Britain. The data yields some insights into what makes the elder Hughes unique, and perhaps offers a note of optimism for the rest of us.

The Lab Data

The classic physiological model of marathon performance involves three parameters: VO2 max, which is basically the size of your engine; running economy, which is the efficiency of your engine; and lactate threshold, which determines what fraction of your VO2 max you can sustain over the course of 26.2 miles.

The two Hugheses are remarkably similar in VO2 max: Tommy recorded a 65.4 ml/kg/min, while Eoin came in at 66.9. Tommy’s is the more remarkable result: a typical value for a sedentary 59-year-old would be somewhere around 30. They also both have very good but not out-of-this-world running economy at marathon pace: Tommy’s was 209.6 ml/kg/km and Eoin’s 199.6. In this case, a lower number is better, meaning you’re burning less energy to maintain a given pace. Those values are typical for good marathon runners, though some have values as low as 185.

The most interesting detail is the sustainable fraction of VO2 max. Tommy’s average marathon pace required him to be working at 91 percent of his VO2 max, while Eoin was at 85 percent. Back in 1991, when Mayo Clinic physiologist Michael Joyner was trying to calculate the , he estimated that marathon pace is typically between 75 and 85 percent of VO2 max, though he noted anecdotal reports of elite runners who were able to sustain 90 percent for a marathon.

As it happens, that very point was the subject of debate recently when researchers at the University of Delaware , Gene Dykes, who ran 2:54:23 at age 70 in late 2018. Dykes’s VO2 max of 46.9 ml/kg/min suggested that he had run his entire marathon at about 95 percent of VO2 max, a seemingly preposterous conclusion that elicited in the New England Journal of Medicine.

With Hughes now also registering a value of greater than 90 percent, it may be worth considering whether one of the superpowers that distinguishes great masters marathoners is the ability to run entire marathons very close to their VO2 max. Alternatively, Lepers points out, we may simply be underestimating the true VO2 max of older runners because they have trouble reaching their absolute limits in treadmill tests to exhaustion. In support of that idea, Tommy’s lactate levels when he stepped off the treadmill at the end of the VO2 max test only reached 5.7 mmol/L, while Eoin got up to 11.5 mmol/L. Since lactate is a marker of distress from high-intensity exercise, that suggests there may be some factor—certainly not mental toughness, given his race results—that forces Tommy off the treadmill earlier than his son.

The Preparation

I omitted an important detail about Tommy Hughes: he’s not just some guy. Back in 1992, he ran a 2:13:59 marathon and represented Ireland at the Barcelona Olympics. After that high point, he took a 16-year break from running, beginning again at age 48.

These days, he reportedly trains much the same as he did in his heyday. Lepers and his colleagues used Garmin watches to track the training of both father and son for two months leading up to the Frankfurt Marathon. According to that data, Tommy averaged 112 miles per week during those months, mostly steady running with local road races as speed work. Eoin averaged 87 miles per week.

The paper also reports some other charming details. For example: “Father and son had very similar basic dietary habits. They eat porridge oats with fresh or dried fruits for breakfast, a [whole-wheat] sandwich for lunch, and potatoes or rice or pasta with vegetables and mostly chicken for dinner. The father also drinks a small glass of organic beetroot juice every day. In the last few days before the marathon, they ate plenty of pasta.”

Both men wore the Nike Vaporfly Next% in Frankfurt.

The Trajectory of Decline

Tommy’s training and racing history leaves us with a tricky dilemma. Is his amazing speed as a 59-year-old mainly a result of the fact that he’s hugely talented, as indicated by his earlier Olympic-level achievements? Clearly his training also plays a role—but is it more noteworthy that he trains extraordinarily hard now, or that he didn’t train at all between the ages of 32 and 48, potentially “saving his legs”?

It’s impossible to draw any firm conclusions from Hughes’s story alone. But his data fits into a larger picture that’s discussed in in Sports Medicine, from an international team of researchers (including both Lepers and Joyner) led by Pedro Valenzuela of the University of Alcalá in Spain. This paper explores the role of lifelong endurance exercise as a countermeasure against age-related decline in VO2 max, which they note is a strong predictor of both how long you live and how functional you’ll be in your later years.

One of the questions they consider is how much age-related decline in VO2 max is inevitable. The conventional view is that as you get older the decline gets steeper, with a “break point” sometime after you turn 70. But if you look at people like Hughes, who continue to train hard as they age, the picture is different.

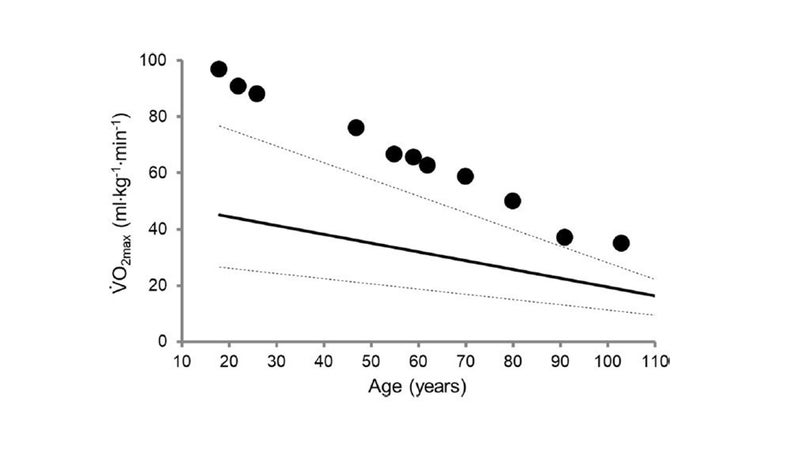

In the graph below, the solid line shows average VO2 max values for different ages according to American College of Sports Medicine reference values. The dotted lines show the 5th and 95th percentiles. (The ACSM reference values only go up to the 65 to 75 age category, so the lines beyond that are just extrapolations.) The black dots show examples of elite athletes of different ages, ranging from Oskar Svendsen’s 96.7 ml/kg/min at age 18 to at age 103. Hughes’s 65.4 at age 59 is one of the dots.

The good news: while the data is sparse, the masters athlete dots make a pretty straight-looking line. There’s no evidence that VO2 max values fall off a cliff beyond some break point. That doesn’t mean this sort of gradual linear decline comes easily. Tommy Hughes, after all, is training pretty much as hard as he did when he went to the Olympics. But it suggests that the steepest declines probably happen when you start exercising less, not simply as a result of hitting a particular age. As Valenzuela and his colleagues note, more longitudinal studies are needed, following the same people over many years, to see whether regular training can keep declines on a linear trajectory. Let’s hope Hughes provides us with some data like this: he turned 60 in January, and is aiming to rewrite the record books in his new age category.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book .