In the early 1970s, a fledgling pro circuit called the International Track Association tried to break track and field loose from the ossified grip of amateurism. One of its innovations was the use of track-side lights that flashed around the oval at a predetermined pace, giving both athletes and spectators real-time feedback on exactly how fast the runners were moving. In theory, this should have helped smash records—after all, you just program the system for, say, a 3:56 indoor mile, then tell your big stars, Kip Keino and Jim Ryun, to follow the flashing lights. In practice, it’s not that easy. “How can I beat the lights?” Keino before a 1973 ITA meet in Los Angeles. “That’s electricity and I am only a human being.” He ended up running 4:06.

The current king of the oval, 23-year-old Ugandan Joshua Cheptegei, in contrast, takes a more optimistic view of things. Before last week’s Diamond League opener in Monaco, he announced to the world that he intended to break Kenenisa Bekele’s 16-year-old world record over 5,000 meters—a record that no one other than Bekele himself had since . A longshot? Not according to Cheptegei, whose own track best of 12:57.41 was more than 20 seconds slower than Bekele’s record. “I believe I can do extraordinary things,” , “so it is a realistic goal.”

And so it was. Cheptegei , slicing almost two seconds off Bekele’s record. In doing so, he beat the lights—specifically, the Wavelight system that World Athletics . Much like the ITA’s set-up, Wavelength sends a beam of lights flowing smoothly along the inner curb of the track at whatever pace you program into it with your phone. For Cheptegei’s race, the lights were set at world record pace. The result? His performance was perhaps the most evenly paced 5,000-meter record ever run. (A video of the race is .)

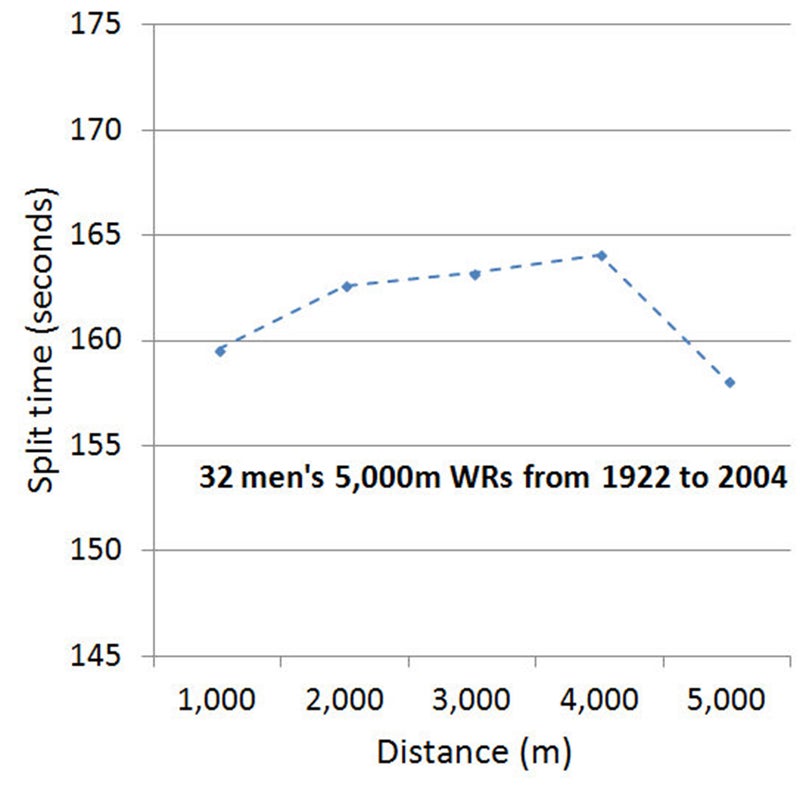

Back in 2006, South African researchers Ross Tucker, Michael Lambert, and Tim Noakes of pacing in world records for races between 800 and 10,000 meters. The key finding was that, for distances longer than 800 meters, the data showed a very distinctive pattern featuring a fast start, a steady pace (with perhaps a gradual slowdown) in the middle, then a fast finish. Here’s what the average kilometer splits looked like for 32 men’s 5,000-meter records starting in 1922 and finishing with Bekele’s 2004 record:

The near-universality of this pattern suggested that we’re somehow wired to pace ourselves like this—that even the fastest runners in the world, running at the outer limits of their capabilities, tend to hold a little bit in reserve until they’re approaching the finish line. But this approach doesn’t seem optimal. If you can sprint the last lap, or even the last kilometer, doesn’t it suggest that you could have spread your effort out more evenly and run faster?

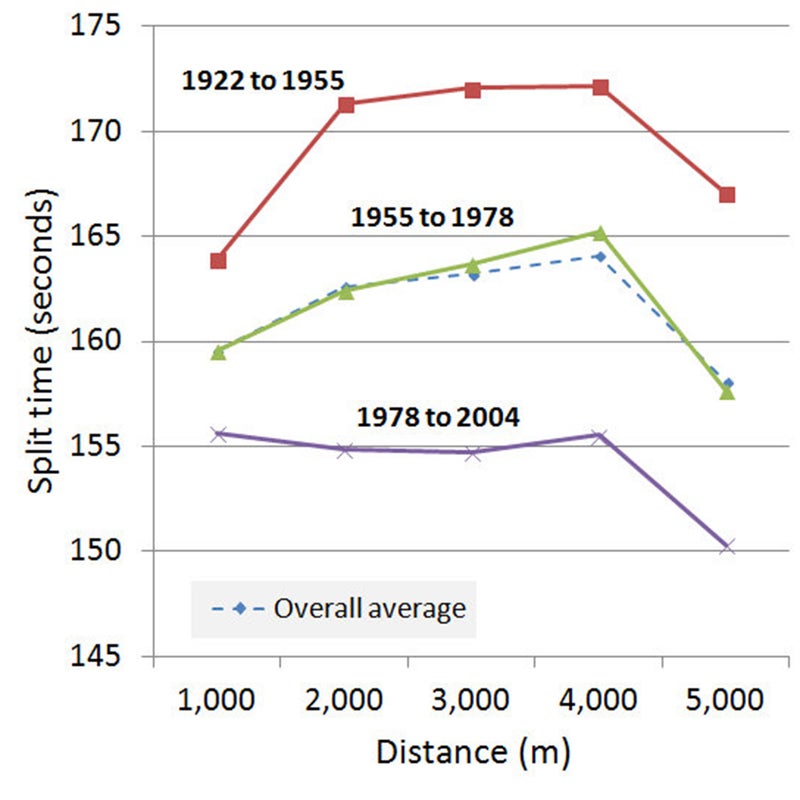

A couple of years ago, Tucker in which he presented a coda to those findings. Even though the general shape of the curve is fairly consistent, it has been evolving over the years. When he broke the data down into three epochs (pre-1955, 1955 to 1978, post-1978), a progression emerged:

The most uneven pacing came in the first epoch, with massively fast starts, dramatic slowdowns, then big re-accelerations. The middle period looks exactly like the overall average. But in the most recent records, the initial fast start has disappeared, and the middle portion of the race is remarkably even instead of drifting slower—but there’s still a big speed-up in the final kilometer. In his video, Tucker suggested that one indicator that runners are finally approaching their ultimate limits would be the disappearance of that finishing kick. If you manage to spread your energy out perfectly, then it will take everything you’ve got simply to maintain your pace to the finish line.

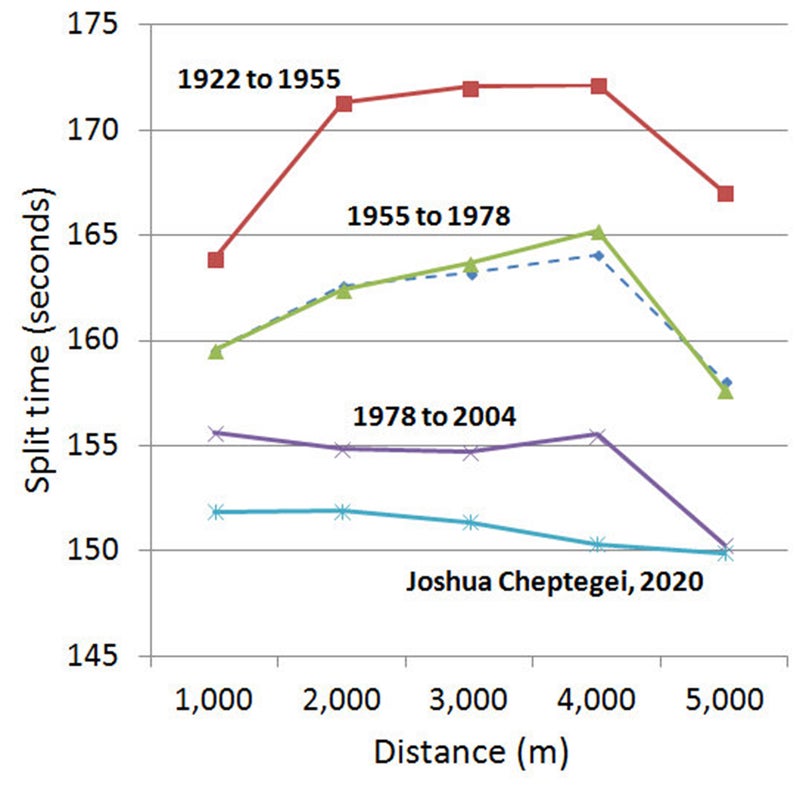

So, with no further preamble, here’s what Cheptegei’s pacing looked like:

It’s not perfectly even, but it’s pretty impressive: a steady start, followed by a very gradual acceleration over the second half of the race. His last kilometer of 2:29.90 was still the fastest of the race, but it was only marginally faster than the penultimate kilometer, which was 2:30.32. With a few laps left, I initially thought he was going to smash the record by five or six seconds, because I’m so accustomed to seeing spectacular finishing sprints from the world’s best runners. But Cheptegei didn’t have any big reserves left.

How did he manage to execute such a finely paced race? He had three pacemakers, who did an excellent job. (That’s not a given: in the men’s 1,500 at the same meet, the pacemaker completely botched it despite the lights, taking the leaders through a first lap of 52.59 and a second lap of 58.65.) Even after the last pacemaker dropped out at 2,400 meters, he still had the Wavelight system to keep him on track. And he also has the ability, seemingly rare these days, to run hard from the front without holding anything back for the finish. That approach bit him , when, as a 20-year-old running in front of a home crown in Uganda, he took a 12-second leap into the final loop before cratering. He barely made it to the finish for a painful-to-watch 30th place. But it has paid off in many races since, and it paid off here.

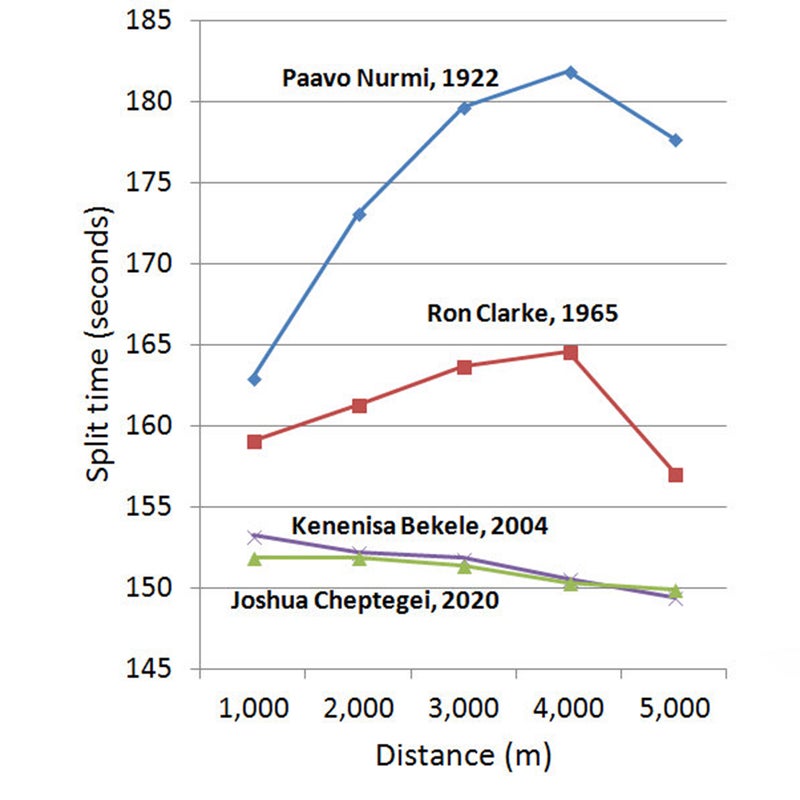

To be fair, the difference between Cheptegei’s and Bekele’s runs is subtle. Here are the splits for a few individual records, including the two most recent ones. You can see that Bekele started a little more cautiously, giving up 1.37 seconds in the first kilometer alone. He was able to speed up more in the final kilometer, but Cheptegei’s more even pacing got him the record.

It’s also worth acknowledging some of the caveats that inevitably accompany new distance-running records these days. Most notably, Cheptegei was reportedly wearing a new iteration of Nike spikes called , which feature the same ZoomX foam as the controversial Vaporfly road running shoes. We don’t know anything about its performance characteristics at this point, but it’s reasonable to guess that it may be faster than previous spikes. And there are also the usual questions about drugs, particularly in light of imposed by the pandemic. To my knowledge, there are no specific rumors or accusations regarding Cheptegei.

In online chatter and discussions with friends since Cheptegei’s race, most people seem to believe that 2004 Bekele would beat 2020 Cheptegei in a fair head-to-head match-up. I tend to agree, mostly because of the potential edge provided by the shoes. Of course, we see Bekele’s run through the lens of all the World and Olympic gold medals he went on to win. Cheptegei is still young, and we may someday look back on this race as the official start of his era of dominance. It’ll be fun to see what he can do—and if he, or anyone else, can get that pacing pattern even closer to the elusive goal of perfectly even splits.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .