The endurance athleteÔÇÖs equivalent of ÔÇťthe dog ate my homeworkÔÇŁ is ÔÇťI think my iron levels are low.ÔÇŁ WeÔÇÖve all been there, after a bad race or a streak of crummy workouts, searching for an objective and an easily fixed explanation for our troubles. Sometimes itÔÇÖs true, sometimes itÔÇÖs notÔÇöthe only way to know for sure, as I wrote last year, is to get your hemoglobin, ferritin, and perhaps transferrin saturation tested.

LetÔÇÖs say you really do have low iron. The next step is to fix it, which is another complex topic. You can eat liver, take pills, get injections, and so on. But your absorption will depend on when you take it, what else youÔÇÖre eating, and even whether youÔÇÖve just done a hard workout. That complexity makes it an area of ongoing research, which is why itÔÇÖs worth taking a look at three recent studies on iron supplementation for athletes, all from the laboratory of Peter Peeling of the University of Western Australia and the Western Australian Institute of Sport.

Patch It

The biggest problem with oral iron supplements is that theyÔÇÖre associated with gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, cramps, and constipation. One way of avoiding all that is to bypass┬áthe gut by using injections (more on that below), but a relatively recent alternative is to absorb┬áiron from a patch on the skin. ThereÔÇÖs an iron patch advertised by , but according to Peeling and his colleagues, there hasnÔÇÖt been any independent testing to ascertain┬áwhether it really works.

So, in in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, they recruited 29 trained runners (nine men and 20 women) with suboptimal iron levels. Fourteen of them wore the iron patch on one shoulder for eight hours per night for eight weeks; the other 15 took an iron pill upon waking every morning. The outcome of interest was ferritin, a measure of iron storage.

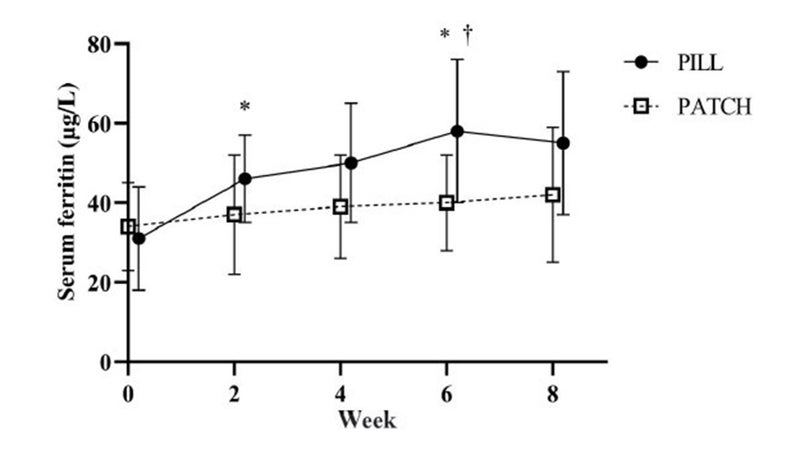

Unfortunately, the results were pretty clear. The iron pill, with a dose of 325 milligrams of ferrous sulphate (equivalent to 105 milligrams of elemental iron), which has been shown to be effective in previous studies, increased ferritin stores by about 60 percent. The patch, which was supposed to provide 45 milligrams of iron every night, didnÔÇÖt move the needle. HereÔÇÖs what the ferritin data looked like:

ItÔÇÖs worth noting that six of the 15 subjects in the pill group reported ongoing GI problems during the study, and one couldnÔÇÖt even finish the study. For that reason, the researchers still like the idea of an iron patch, and they describe some research identifying the challenges and working toward solutions. But the bottom line is that, in its current commercial formulation, it doesnÔÇÖt seem to get through the skin.

Skip a Day

If youÔÇÖre stuck with iron pills, you might wonder whether you really have to take them every day. In fact, thereÔÇÖs a possible rationale for skipping every second day, because your ability to absorb iron is suppressed for about 24 hours following a high dose. So, in to the patch one, the same researchers had a third group of 16 runners take the same 325-milligram dose of ferrous sulphate every second day┬áand compared their results to the pill-every-day group from the patch study.

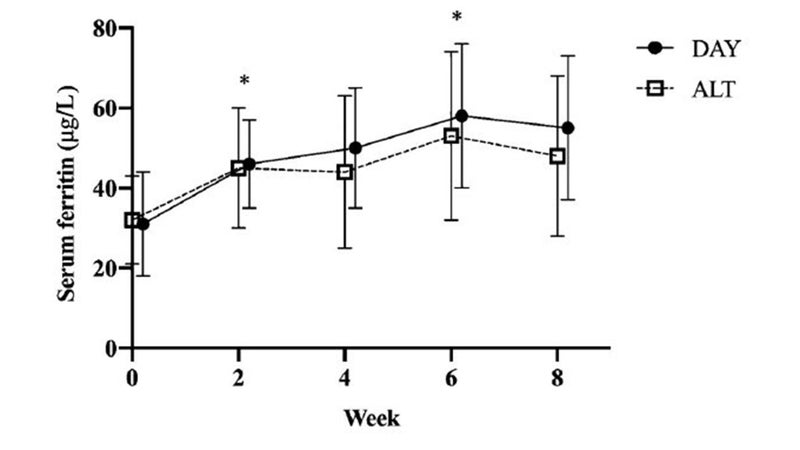

In this case, the results in the two groups were nearly identical, even though the alternate-day group only took half as much iron. Both groups increased their ferritin levels by about 60 percent:

And if saving money on your iron supplements isnÔÇÖt incentive enough, the alternate-day group only had one report of GI symptoms. That makes it more likely that athletes will stick with their supplementation plan in the real world.

Get a Shot

In the third study, , Peeling and his colleagues examine the nuclear option. For athletes with iron problems, you typically start by trying to fix it with dietary changes, then you progress to oral supplements. But in particularly serious or recalcitrant cases, you can directly inject iron either intravenously or into the muscle.

The new study is a retrospective analysis of 16 athletes from the Western Australian Institute of Sport, who received a total of 22 intravenous injections of 1,000 milligrams of iron (in the form of ferric carboxymaltose) in recent years. What the researchers were interested in was how well the injections worked and how long their effects lasted. Since the athletes at the sports institute received regular blood testing, the researchers were able to track the effects for as long as two and a half years after the injection.

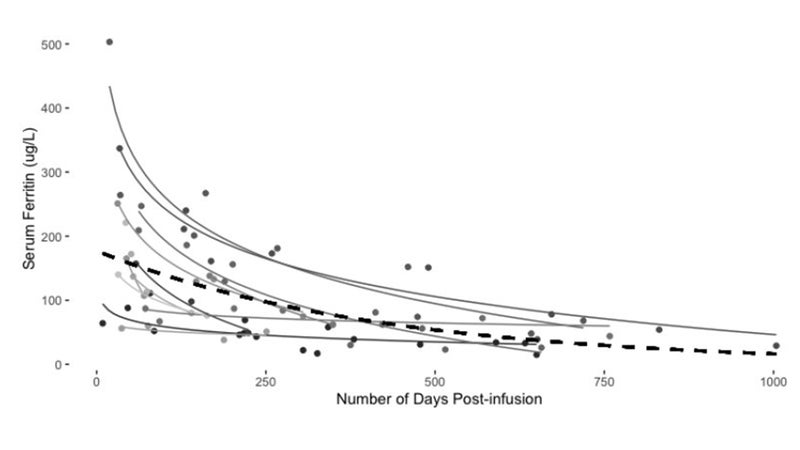

The basic finding is that your mileage may vary. Ferritin levels rose sharply in some athletes and modestly in others, and they dropped quickly in some and slowly in others. Those who received more than one injection seemed to have similar results each time, which suggests that individual differences, rather than mere random variation, explain the divergent results.

HereÔÇÖs what the overall data looked like, showing the decay of ferritin levels for up to 1,000 days following the initial injection. Each thin line represents a different athlete:

The main advice that Peeling and his colleagues extracted from this data is that athletes who receive an intravenous iron injection should get their iron levels tested one month after the injection to see how much their iron stores increased, and then they should get tested again six months after the injection to see how fast their levels are decaying. That time frame should be sufficient to catch even the poorest responders before they slip back into serious deficiency.

In practice, very, very few of us will ever get an iron injection, and those who do will (hopefully) get┬áit under the close supervision of an experienced sports-medicine physician. Until patches prove themselves, the rest of us will have to make do with oral supplementsÔÇöif we need anything at all, that is. Sometimes, much as we hate to admit it, a bad race is simply a bad race.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .