There is no magic workout. I used to get frustrated with my training partners when they’d start stressing about whether we should take 90 seconds or two minutes between repetitions, or argue about whether we should be running 1,200-meter reps instead of 1,000 meters. Those minor details aren’t crucial.

But that doesn’t mean that all interval workouts are equal, as in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research reminds us. Researchers at Berry College in Georgia put eight volunteers (half of them men, half women) through four different workouts and measured the physiological and perceptual responses. The results offer a useful snapshot of what different types of intervals involve, and—perhaps unintentionally—highlight a crucial divergence between the raw numbers and what you feel during and after a workout.

The four workouts were as follows, all performed on an exercise bike and preceded by a warm-up:

- 4 x 30 seconds hard (all-out), with 4:00 recovery (very easy cycling at 50 watts)

- 12 x 60 seconds hard (100% of power at VO2max) with 60 seconds recovery (50%)

- 4 x 4:00 hard (90%) with 3:00 recovery (60%)

- 45:00 steady (90% of power at lactate threshold)

The intensities for the middle two workouts were set based on the max power achieved during a previous VO2max test.

The researchers collected a bunch of data on how the subjects responded to the workouts, so I’ll just point out a few highlights. One of the goals of the experiment was to determine what physiological changes occurred during the 30 minutes after the workout ended. The general conclusion was that people recovered at pretty much the same rate for all workouts, with no differences in how long metabolism stayed elevated. In other words, there’s no magic afterburn that melts appreciable amounts of fat away in the hours after a high-intensity interval workout. Sorry.

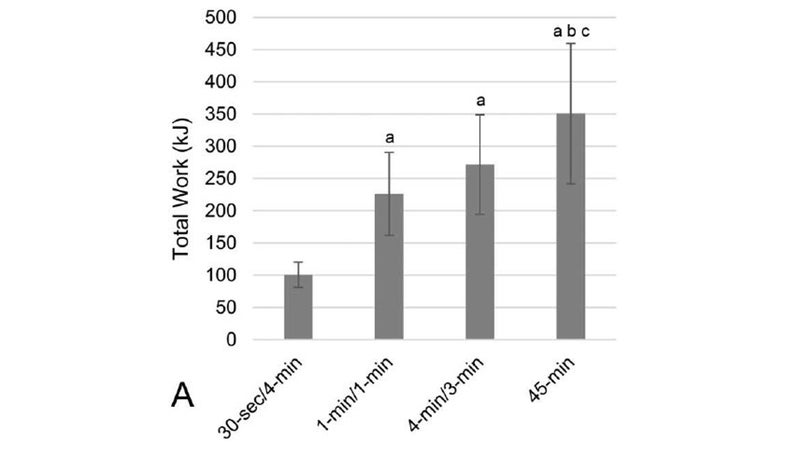

The most objective way of measuring the demands of the workout itself is to look at the total work completed, which is measured in kilojoules. In theory, a short training session can require the same amount of work as a long one if it’s at a high enough intensity. But for these four sessions, the amount of work was clearly greater in the longer reps or continuous effort:

This isn’t really surprising. The 30-second reps took a total of 14 minutes, including recovery time; the one-minute reps took a total of 23 minutes; the four-minute reps took a total of 25 minutes; and the 45-minute continuous ride took a total of… well, you get the point. This is why high-intensity interval training studies have generated such excitement over the last decade or so: shorter workouts involving much less total work seem to, in some cases, generate similar fitness gains as longer ones.

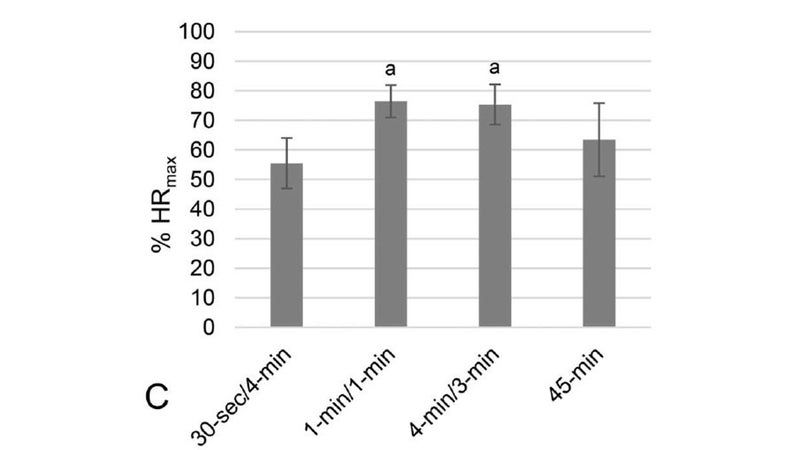

If you’re looking to improve your aerobic fitness, the picture might be slightly different. Here’s what the overall average heart rates were, as a percentage of max, for each workout:

In this case, the long recovery period between 30-second sprints means that the average heart rate for the workout is quite low. The pattern is similar if you look at the fraction of VO2max sustained during the workout. The hardest aerobic challenges, instead, seem to be the longer intervals, which fits with that concluded that the most effective interval durations to raise VO2max were in the three- to five-minute range. The really interesting question, to me, is how hard each of these workouts is. That’s not very realistic, as this study illustrates: total work is mostly just a function of the overall duration of the workout. For example, the total work in the 30-second sprints was 100 kilojoules, while the 45-minute steady sessions required 350 kilojoules. To equalize the total work, you’d either have to increase the number of sprints from 4 to 14, or shorten the 45-minute ride to just under 13 minutes. Neither option gives you a realistic comparison of how people actually do these sorts of workouts.

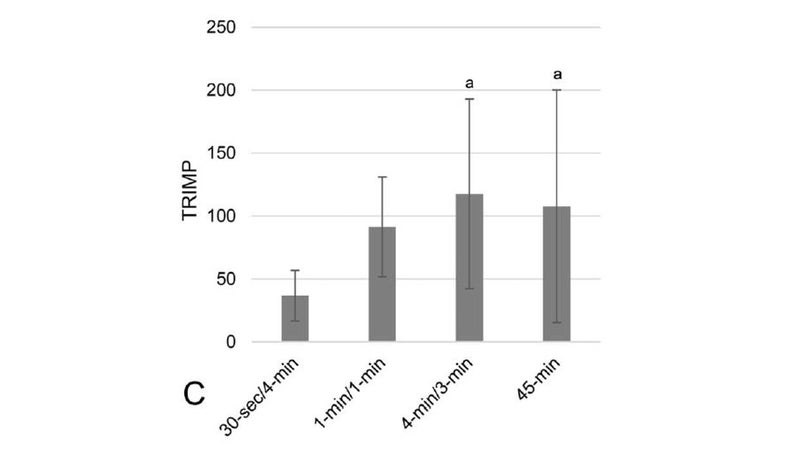

In the new study, the researchers looked at a couple of other options for measuring how hard the session is. One is a measure called “,” which is a fairly intricate calculation that involves taking average heart rate for each 5-second period during the workout, multiplying it by a weighting factor derived from the individual’s heart rate-lactate curve, and then summing all the five-second contributions. This approach aims to give you an overall estimate of how hard you pushed your body, by combining intensity and duration. Here’s what that looks like for each workout:

By this measure, the sprints are easy compared to the longer intervals and the steady run.

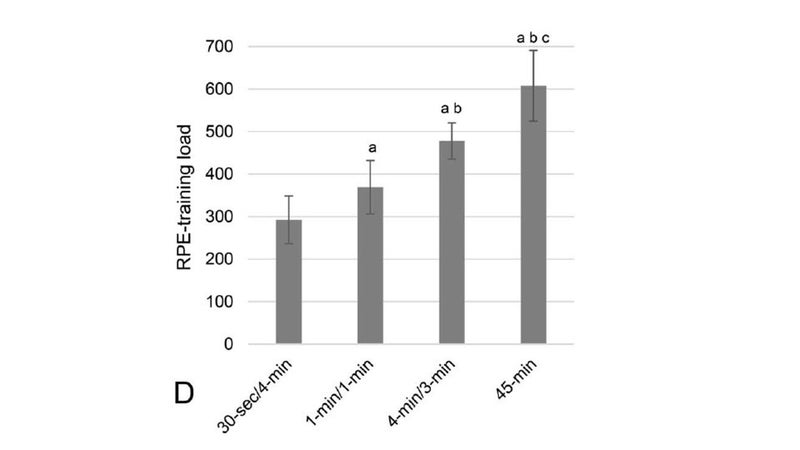

Another option is “RPE-training load,” which is simpler: you take the athlete’s subjective estimate of how hard the overall session was (their rating of perceived exertion, or RPE, on a scale of 6 to 20, assessed 30 minutes after the session finishes), and multiply it by the total duration of the session. Here’s how that looks:

Once again, the total duration of the workout dominates, and the sprints appear to be the easiest.

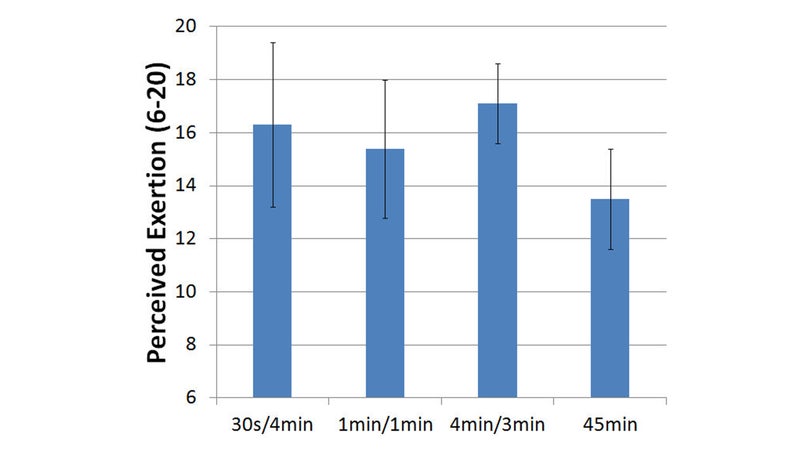

There’s one graph that didn’t make it into the paper, though: the simple RPE rating for the overall session. How hard did the subjects find each workout? Here’s my own graph of the RPE data from the paper:

Now we’re looking at a completely different picture! The 45-minute steady session, even though 90 percent of lactate threshold is not exactly lollygagging, is by far the easiest session overall. The three interval workouts are all pretty similar—and hard. So the total amount of work performed in the session is a terrible predictor of how hard it is.

If you’re a hardcore athlete, this may be irrelevant to you. You’ll do whatever workout you think will improve your performance the most, no matter how hard it feels. If that’s the case, there are different advantages for each of the three interval workouts described here (for more on choosing the details of interval workouts based on your goals, check out this article from a few months ago).

But if your focus is health, and you’re trying to find a workout routine that you’ll be able to stick with in the long term, then you need to think carefully about what barriers you’re trying to overcome. Is it, as many high-intensity interval advocates argue, a lack of time that makes you miss workouts? If so, nothing rivals the time-efficiency of short sprint workouts like the 30-second reps. Or is the real barrier, as , the fact that your workout feels unpleasant? If that’s the case, the plain old 45-minute steady session looks like a better option, since it’s rated as the easiest (and thus presumably the most pleasant) option.

Personally (as always!) I’m in favor of a mix of all of the above—but I would never suggest that all-out sprint workouts are easy just because they’re short and, objectively speaking, don’t involve much total work. The reason they’re so effective is that they’re very, very hard.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .