Close your eyes and imagine this scene. You’re entering the weight room. You sit down on a bench and collect your thoughts, recalling how many sets and reps you plan to do, with how much weight and how much rest. Now you head over to the Smith machine, unrack the bar, and prepare to do a back squat: down for two seconds until the legs are bent at 90 degrees, then thrusting upward as forcefully and fast as possible. Repeat as desired—and boom, you just got stronger while reading this paragraph.

The power of mental imagery is well-known to the point of cliché, and scientists have been studying it . It’s mostly viewed as a way of getting in the right headspace, or else as a showing that imaginary exercise can get your heart pumping. But when the pandemic sent professional athletes into lockdown last year, some of them were willing to try seemingly outlandish tactics to avoid losing their fitness. A , led by Antonio Dello Iacono of the University of the West of Scotland, tells the surprising story of how the Glasgow Rocks, the then-top-ranked team in the British Basketball League, stayed in shape last spring.

When the pandemic hit Scotland, team workouts stopped and players had to work out alone at home. The training staff decided to allocate 30 players from the senior and under-19 squads, all of whom had been healthy and playing prior to the pandemic, to three groups of ten. For six weeks, one group imagined doing a strength-focused workout routine three times a week; another group imagined doing a power-focused workout routine; and a third group didn’t do any mental imagery training.

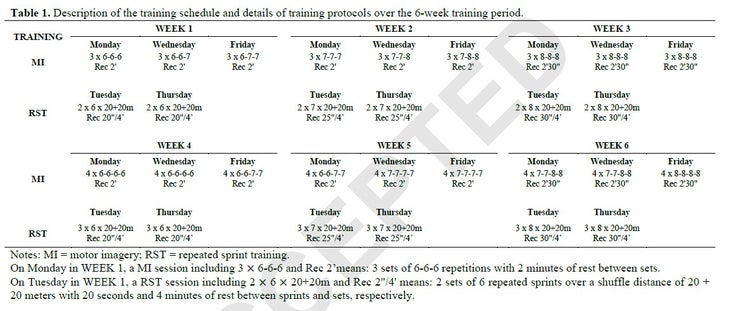

The big differences between this study and most previous mental imagery studies were that they used high-level athletes, and that the workouts mimicked exactly what you’d do in the weight room. On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, they imagined sets of back squats and bench presses, starting with three sets of six reps and progressing to four sets of eight reps. The strength group imagined lifting at 85 percent of one-rep max; the power group lifted at a slightly lighter “optimum power load” that had been individually determined for each athlete in testing prior to the pandemic, ranging from 55 to 65 percent of one-rep max. (Power is a combination of the weight you’re lifting and how quickly you lift it, so there’s a sweet spot that maximizes that combination.) On Tuesday and Thursdays, everyone including the control group did some short sprints.

After the six-week training period was finished, the athletes returned to the lab for more testing. The control group, languishing in their apartments binge-watching Outlander, got three percent weaker in the back squat and four percent weaker in the bench press. The strength group, in contrast, gained nine percent in their back squat one-rep max and seven percent in the bench press. The power group also gained strength, though slightly less: five percent in the back squat and two percent in the bench press.

Conversely, the power group did slightly better in vertical jump, a measure of lower-body power: they gained 0.7 centimeters, compared to 0.2 in the strength group. The control group lost 1.9 centimeters. A similar trend was observed for seated medicine ball throw, a measure of upper-body power. In other words, it’s not just that mental imagery works. Its specific effects seem to depend on exactly what you imagine yourself doing. In this case, the only difference between the training imagined by the two groups was how heavy the weights were!

Normally you’d like to hook up the athletes to a bunch of electrodes, or even put them in a brain scanner, in order to figure out exactly how and why they got stronger. In this case, pandemic restrictions precluded this type of analysis. Based on previous studies, the researchers surmise that imagining a series of movements as realistically as possible recruited the same parts of the brain and activated the same signaling pathways in the spine as the real action would have. Doing it repeatedly rewired the neural circuitry, enabling the subjects to use more muscle fibers for a given movement, or drive them more intensely.

This is a result that you might reasonably hope to never, ever have to use. But even in the absence of future pandemic lockdowns, there might be situations where it’s useful. In fact, one of the reasons the Glasgow Rocks were receptive to the idea was that they were already using mental imagery training to practice their shooting. It also seems like a helpful approach to when you can’t yet do real training. And Dello Iacono is looking into the idea of using it for something called , which is the idea that warming up with certain types of exercises might enhance performance. If you could just imagine those warm-up exercises, you might be able to get the neuromuscular benefits without accumulating any fatigue.

Dello Iacono isn’t getting too carried away just yet, though. The pandemic-driven circumstances of this study were pretty unusual, he points out, and it’s impossible to rule out a placebo response among the athletes who got to do some training rather than none at all, even if it was imaginary training. And even if it works, it’s not a free lunch. Doing four mental sets of eight back squats at 85 percent max is time-consuming and hard—but at least it’s one workout where you can be absolutely sure that all the discomfort really is in your head.

The Imaginary Workout Regimen

Here’s the six-week mental training protocol used in the study, which included three days a week of mental imagery workouts and two days a week of real-life sprints.

The strength workouts consisted of two exercises: back squat and bench press. For each exercise, participants imagined a weight calculated from either 85 percent of their one-rep max for that exercise, or a slightly lighter weight of around 60 percent of one-rep max. The former optimized strength, while the latter optimized explosive power.

Here’s a simplified version of the instructions they were given:

- Imagine yourself entering the weight room where the resistance training sessions routinely take place. Imagine yourself sitting on a bench and taking a few moments to recall the training plan for the day’s session: the order of exercises, number of sets and repetitions to complete, as well as the rest interval between consecutive sets.

- Imagine yourself performing the motor sequence: grabbing and unracking the bar, executing the lifts as forcefully and fast as possible, racking back the bar. Do this with your eyes closed by imagining the different movements, as if you had a camera on your head, and perceiving the body sensations. You see and perceive what you would if you actually performed this particular task.

- Complete each repetition with the downward phase lasting about two seconds, and then moving the bar up as forcefully and as fast as possible throughout the upward phase. Don’t move your body.

And here’s a table showing how many sets and reps to do for each workout during the six-week period. The motor imagery (MI) training takes place on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays; the sprint training (RST) takes place on Tuesdays and Thursdays:

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .