In 1969, University of Michigan psychologist Robert Zajonc published showing that cockroaches were able to sprint more quickly if other cockroaches were watching from the sidelines, but did worse at a maze-learning task when they had an audience. It was an intriguing cross-species demonstration of the nuanced way our performance responds to the presence of others, echoing similar results for simple versus complex tasks in humans. It was also a reminder that the effects of run deeper than simply getting psyched up or overthinking things, neither of which cockroaches are prone to doing.

I recently found myself reading about Zajonc’s cockroaches thanks to , published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research and led by , of Edge Hill University in Britain, on the role of spotters in bench press performance. Numerous studies over the years have shown that working out with a personal trainer leads to greater gains in strength, but the reasons have never been clear. Is it that trainers give better advice, or set tougher goals, or yell motivational slogans at you? Or is their mere presence an ergogenic aid?

In the new study, Sparks and his colleagues asked 12 volunteers, all with at least a year of weight-training experience, to perform three sets of bench presses at 60 percent of their one-rep max, all to failure and with two minutes of rest between each set. They did this test twice, on two separate days, once with two spotters on either side of the bar and once with no spotters visible. (The spotters were actually still there but were hidden behind a screen so the volunteers couldn’t see them while lifting.)

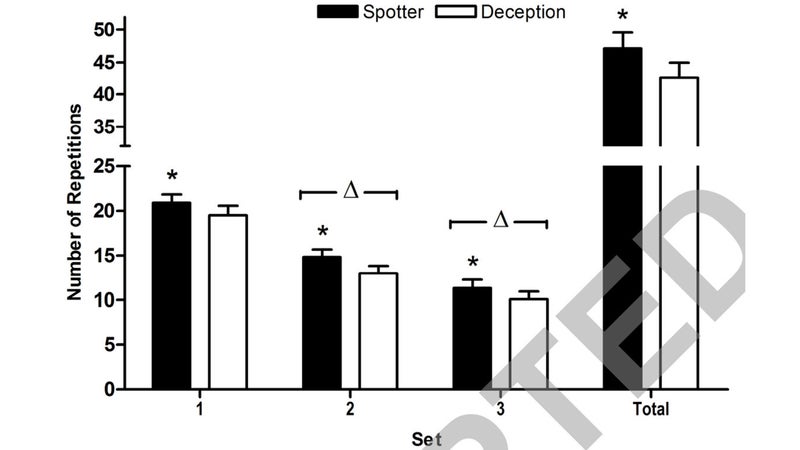

As expected, the volunteers managed to squeeze out more reps when they knew the spotters were watching than when they didn’t know, lifting a total of 11.2 percent more weight. Here’s how the performance in each set looked:

What’s interesting is how the volunteers perceived their efforts. After each set, they were asked to rate how hard it was, both overall and for their arms and chest. They consistently said they were working harder when no spotters were there, even though they were actually completing fewer reps. On the Borg scale of perceived exertion, which runs from 6 to 20, they rated the first set as 10.8 with spotters and 11.7 without; the second set was 13.0 and 14.0.

The volunteers were also asked about their self-efficacy, which is a measure of your belief in your ability to succeed at a given task. Specifically, after the first and second set, they were asked: “How confident (on a scale of 1 to 10) are you that you will match the previous number of repetitions?” With a spotter, the average answer was 6.4 after the first set and 6.3 after the second set. Without a spotter, even though the number of repetitions to be matched was lower, the averages were 4.4 and 4.9.

As the researchers point out, there has been plenty of research on the performance-boosting effects of competitors in endurance performance and of large crowds on weight-lifting performance. But the mere presence of an additional two silent strangers seems like a very subtle change in conditions given the large difference in outcome. If it was simply a case of wanting to impress onlookers, you’d expect their reported effort would be higher, not lower (though I suppose it’s also possible that the lower effort ratings in themselves are an unconscious attempt to impress: #nbd).

But as Zajonc’s cockroaches suggest, I think something more fundamental is going on here. One of my favorite studies in this vein is by cognitive and evolutionary anthropologist Emma Cohen with Oxford University rowers, which found that doing a rowing machine workout alone in a room boosted pain tolerance, presumably due to a surge of brain chemicals such as endorphins—but doing the exact same workout in a room with teammates produced a far greater increase in pain tolerance. by Cohen has found that warming up with a teammate produces better performance in a running test—and the effect is even greater when the warm-up exercises are performed in sync (a finding, Cohen suggests, that may be deeply rooted in our evolutionary need for group cooperation).

In other words, we’re wired to respond to the presence of other people. They can help you dig deeper, or, conversely, they can help make a given level of exertion feel easier. That’s something many of us discover intuitively from training with a group, and it’s why I’m willing to commute these days to meet up with friends for my hard workouts. And as Sparks’ study reminds us, those other people don’t have to yell at us, offer technical guidance, or even say anything at all. All they have to do is show up.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available! For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .