Earlier this year, I wrote an article arguing that there’s insufficient evidence to justify broad statements about how to adjust your training around your menstrual cycle. A big part of the problem, according to a major review of the existing research, was that much of it relied on self-reporting to determine what menstrual phase its subjects were in, which is notoriously unreliable. How can you claim that if you’re not sure when the luteal phase starts?

The conclusion of that review was, as you might guess, that more and better research is needed. So here’s a start: new data from the Female Endurance Athlete Project, a Norwegian initiative to fill some of the gaps in knowledge about female-specific aspects of exercise and athletic performance. A team led by Virginia De Martin Topranin of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology assessed recovery status in 41 female endurance athletes as a function of their objectively monitored menstrual cycle. The results, , suggest there are indeed statistically significant differences in recovery at different times in the cycle—but that these differences, at least on a group level, are “negligible to small.”

The athletes in the study ranged in classification from “trained,” averaging about 7.5 hours of training per week, to “elite/international,” averaging about 11.5 hours. They all had regular menstrual cycles and weren’t using hormonal contraceptives. They tracked their periods using a digital ovulation urine test. And they took daily measurements of resting heart rate, perceived sleep quality, physical readiness to train, and mental readiness to train, the latter three on a scale of 1 to 10.

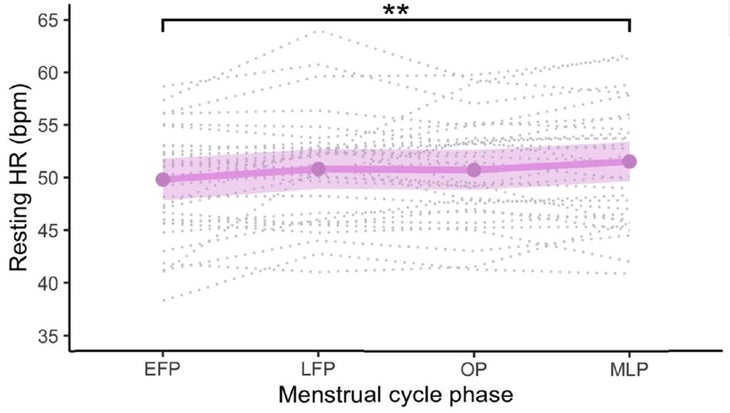

Here’s what the resting heart rate data looked like at four key points in the cycle (early follicular phase, late follicular phase, ovulatory phase, and mid-luteal phase):

The two asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference between the early follicular (49.6 beats per minute) and mid-luteal (51.3 beats per minute) phases. That’s a difference of 1.7 beats per minute, or 3.4 percent. For context, the typical day-to-day variation in submaximal heart rate is about 6.5 percent. Topranin and her colleagues conclude that this difference is real—and indeed, it does agree with previous findings in non-athletes of increased resting heart rate in the mid-luteal phase—but with a marginal effect size and “limited practical relevance.”

There are similar statistically-significant-but-tiny findings for sleep quality (slightly lower in mid-luteal phase compared to late follicular phase) and physical readiness to train (slightly lower in ovulatory and mid-luteal phases compared to early follicular phase). There are plausible explanations for these findings. For example, high progesterone levels in the luteal phase might be associated with elevated body temperature, which could interfere with sleep. In other words, these effects, small though they are, may well be real. The harder question is whether they matter.

On average, a difference of less than 2 beats per minute isn’t likely to move the needle. Same for, say, a difference of around 0.3 out of 10 in perceived sleep quality. But those average results probably mask some larger individual variations. Some people might see no effects at all, while others might see their resting heart rates jump by 4 beats per minute.

To be clear, that’s not necessarily the case. As I discussed in this article, it’s not easy to tell the difference between consistent responders or non-responders and random fluctuations in any training study. Do the same people have unusually strong (or weak) responses with every menstrual cycle? Or is the variation from cycle to cycle bigger than the variation from person to person? This particular study, which only followed subjects for between one and four menstrual cycles, can’t answer that question.

Still, it seems likely that some people will experience consistently larger effects than others. For these people, adjusting training based on menstrual cycle might be more reasonable. But even then, it doesn’t trump all the other factors that determine how well you’re recovering. Menstrual cycle, the researchers point out, “should rather be regarded as one of many possible stressors.” Your recovery might be a little bit slower during the luteal phase of your cycle, but the best way to handle it is to pay careful attention to your training load, other life stressors, and how you’re feeling. That’s good advice that applies to all of us, all the time.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book.