“So maybe you two can tell me,” I shouted over the holiday din. “How can you survive a scalping?”

The Hardest Way West

In this exclusive excerpt from the new book, Astoria, the legendary Overland Party attempts to establish America's first commercial colony on the wild and unclaimed Northwest coast—provided, of course, they survive the journey.��

“Whoa!” someone said. “Now that’s a real conversation stopper!”

My two subjects were standing in a circle of people holding drinks and chatting, presumably about holidays plans or the good work in river restoration, in the middle of a party tent festooned with cheery Christmas lights.

The two of them, doctors Doug Webber M.D. and Gary Muskett M.D., both avid outdoorsmen themselves, have seen all sorts of cases involving wilderness injuries in decades of experience in the emergency room of St. Patrick’s Hospital in our mountain town of Missoula, Montana.

“You’re exactly the two guys I need to talk to!” I had called out when I had spotted them across the tent.

Amid the holiday cheer, they briefly consulted with each other about scalping.

“Under the right conditions,” came back the answer, “you probably could survive a scalping. The issue is how to constrict the blood loss. If it were really cold outside, that would help constrict the arteries. Also, if the cut were jagged and torn rather than clean and sharp, the arteries constrict faster.”

Their answer matched what clues I’d picked up from historical accounts.

“That makes perfect sense,” I replied. “The duller the knife—like a stone knife—the better your chances of survival. And if a partial incision was made around your skull, and then the rest of the scalp torn off in a single jerk—that was the usual technique—that would increase your chances of survival even further!”

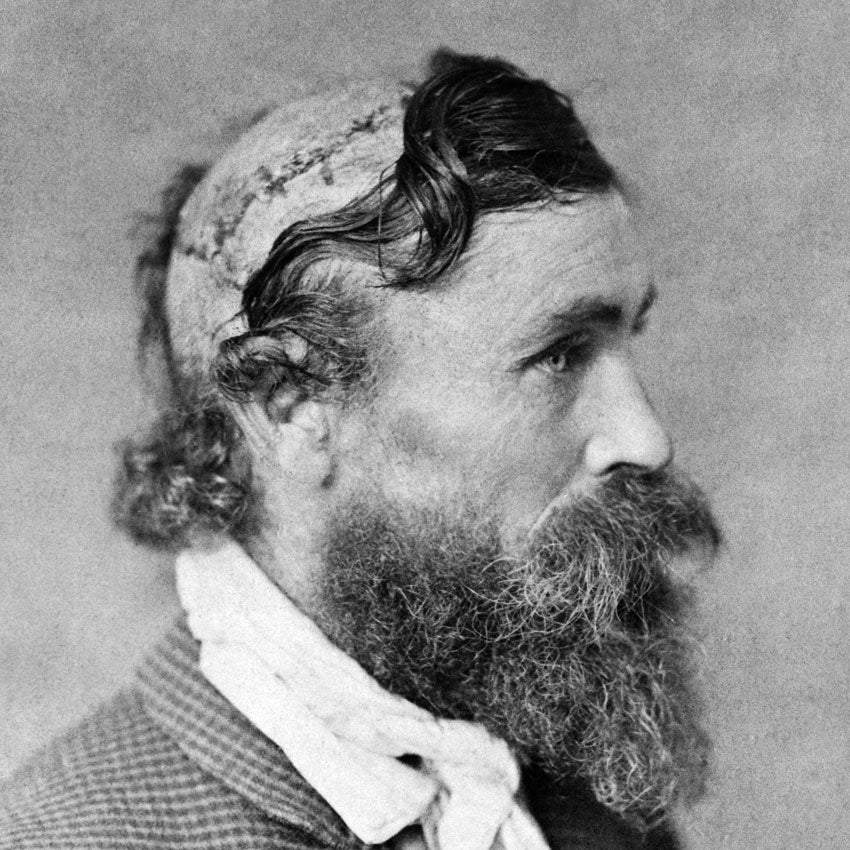

I’d been writing about a pivotal, if little known, figure in the exploration of the American West in my book, , Edward Robinson, who happened to have been a scalping survivor. The shocking image of the scarred and ridged flesh atop his hairless pate may have, in some way, changed the course of America’s Western empire.

“You probably could survive a scalping. The issue is how to constrict the blood loss. If it were really cold outside, that would help constrict the arteries.”

In 1810, as I recount in Astoria, fur merchant John Jacob Astor, with the enthusiastic backing of Thomas Jefferson, sent two huge expeditions from New York City to the Pacific Coast. Their mission was to found America’s first colony on the West Coast and a trans-Pacific, global trade empire. One expedition sailed around Cape Horn by sea. The other, led by a young New Jersey businessman named Wilson Price Hunt, traveled overland, following the recent Lewis and Clark route up the Missouri River. ��

One problem was that Hunt, a nice, serious-minded, consensus-seeking sort, had no previous wilderness experience. Another was that the farther they rowed their riverboats up the Missouri, the worse the stories they heard about the ferocity of the Blackfeet Indians at the river’s headwaters.

One day in May, as Hunt’s 60-person party breakfasted on the riverbank, two canoes drifted down carrying three white men.�� The three had survived a major massacre by the Blackfeet with a party trying to establish a fur post at the Missouri headwaters. One of the trappers, the 66-year-old Kentuckian Robinson, wore a scarf around his head. Under it were the scars of a scalping.

He had this advice for the wilderness neophyte Wilson Price Hunt: Avoid the Blackfeet at all costs.

The Blackfeet were implacable and still furious that Meriwether Lewis’s party had killed two of their young men, left a Jefferson Peace Medal hanging around one’s neck, and fled.

Robinson and company said they knew a better way to the Pacific than the Lewis and Clark route, one that left the Missouri, skirted to the south around Blackfeet territory, across several mountain ranges, to a headwaters branch of the Columbia. Here the voyageurs could build canoes and easily paddle to the Pacific to start Mr. Astor’s trans-global empire. In fact, the three trappers wanted a piece of the action, too.

Hunt spent an anxious night agonizing over the decision about route. Surely, in his tossing, the puckered ridges of Robinson’s hairless pate played with his imagination. (Robinson had actually received the scalping some years earlier in Ohio Valley Indian wars.) Finally, Wilson Price Hunt chose. He would take the party away from the Missouri and the known Lewis and Clark route into a thousand miles or more of uncharted terrain.

Hunt’s choice, informed by Edward Robinson’s scalped head, would prove a fateful decision for the American West and the geopolitical shape of the North American continent.

Peter Stark is a full-time freelance writer of non-fiction books and articles specializing in adventure and exploration history. His most recent book,��, tells the harrowing tale of the quest to settle a Jamestown-like colony on the Pacific Coast and will be published in March 2014 by Ecco/HarperCollins.