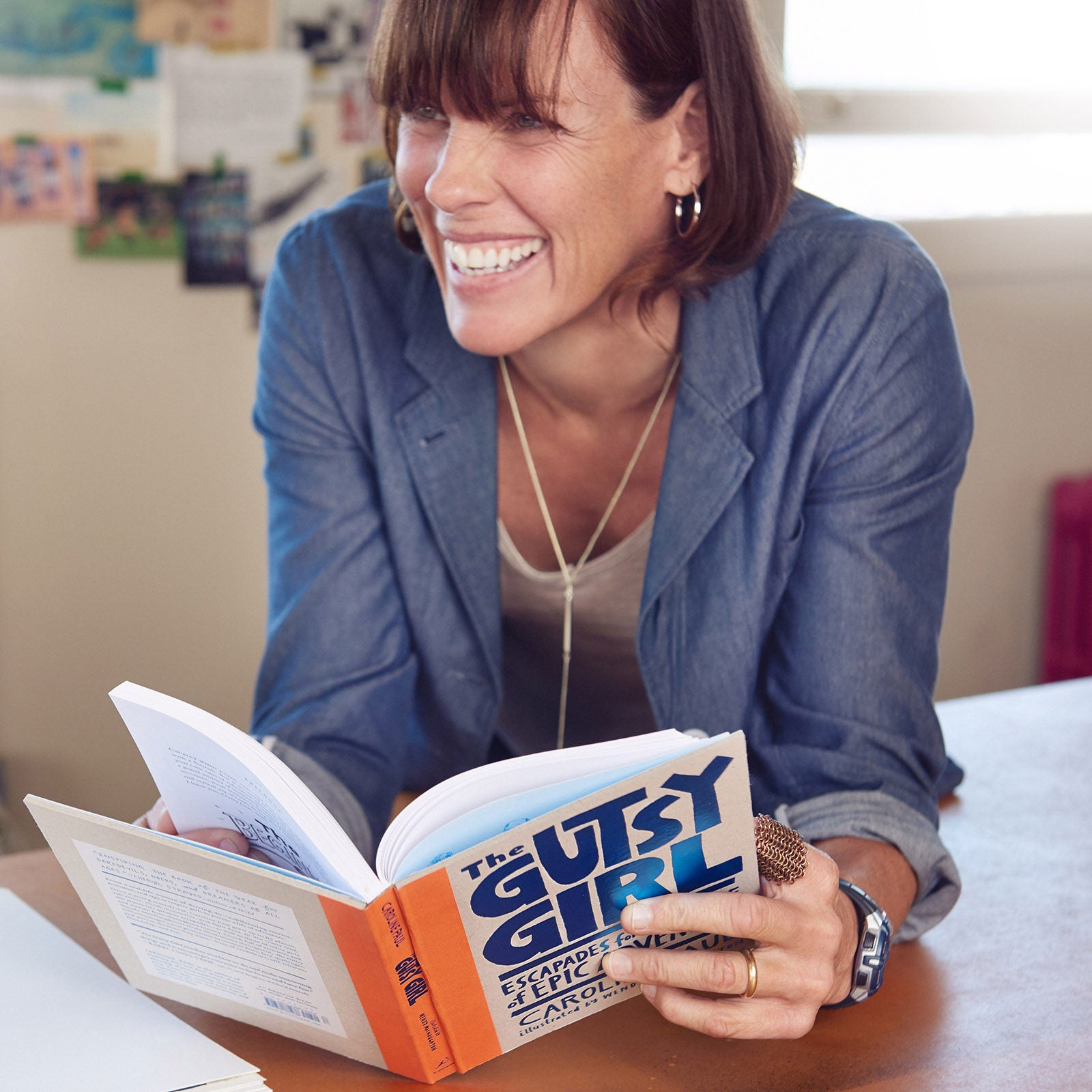

is the author of four books, including the New York Times best seller . Once a young scaredy-cat, she decided that fear got in the way of the life she wanted–one of excitement, confidence, and self-reliance. She has since rafted big rivers, climbed tall mountains (including Alaska’s Denali), and flown ultralight aircraft (making one intense emergency landing). In the late 1980’s, she became one of the first female members of the San Francisco fire department.

In an extended interview for , Paul spoke about her experiences as a firefighter and tactics for minimizing and overcoming various types of fear. Below is an excerpt of their conversation, edited by ���ϳԹ���.

When did you begin to think about becoming a firefighter? And how did you get the job?

When I graduated from Stanford, I wanted to be a documentary filmmaker or journalist. I was volunteering at KPFA, a sort of radical public radio station in Berkeley. They throw you right into doing stories and at the time, in the 80s, there were reports about racism and sexism at the San Francisco Fire Department. I thought, I'll take the test to become a firefighter and do an undercover story. I went through the process and of course, racism and sexism doesn't show up in the ways we expect. You can't just encapsulate them in a two-day test. So I had no story, but I passed every part of the test, which surprised me. All of a sudden, they said, “You're in.”

What makes a good firefighter?

That's a great question. The firefighters I respected often were not the strongest ones. They were fit, but they were smaller and had a lot of street smarts. You need to understand your physical limitations because everybody has them—even the strongest guy. I remember one time being on a smokey stairwell waiting for the firefighter up top to gain entry to the building. He was a big guy and whaling on the door with an axe, but it just wasn't giving way. I said, “Take my pry bar.” He's like, “No!” And he kept whaling at that door. It took so long for that door to come open because he thought, as a big guy, he could do it. Someone else would have just stuck the bar in there, given it a hit on the head, and the door would've popped open. Women and smaller guys, we know our limitations and we're going to compensate.

When you think of being terrified, what moments from your life come to mind?

When I was a firefighter, I was in a building with three others crawling down a hallway. We had a hose line and were looking for the seat of the fire, which can be awesome. It's super smoky hot and kind of quiet in this weird way. And then all of a sudden a huge explosion pushed us all out of the hallway into a garage. Later, we realized later there had been a flashover—when it gets so hot that even the particles in the air ignite—close enough by to blow us all over.

I was discombobulated and my friend Frank goes, “Where is Victor?” Victor was my crewmate and I look around there were just three of us instead of four. I remember thinking, I have to go back into that hallway? The fear was paralyzing. Frank, who is a really great firefighter, catapulted himself towards that door to find Victor. For me, it was only a millisecond, but I was scared. I recognized that fear, and it scared me more than the fire itself. When you're paralyzed as a firefighter and your friend is missing, that's the worst. Of course, I was right on Frank’s heels, but that feeling of overwhelming fear was really sobering.

I learned that you can be scared but still take action if it's necessary. My friend was fine. He had been blown out, but had taken shelter on the other side. It was a moment I'll never forget.

You've written about your ability to put fear behind your other emotions. In one story, you described doing this while climbing the Golden Gate Bridge—which, by the way, is illegal. How did you learn to place courage, desire, or enthusiasm in front of fear?

Fear is important—it’s there to keep us safe. But I do feel like some people give it too much priority. It's just one of the many things that we use to assess a situation.

When we climbed the bridge, it was five us deciding we wanted to do it in the middle of the night—please don't do that. But we did. Talk about fear. You're walking on a cable where you have to put one foot in front of the other and you get higher and higher until you're basically as high as a 70-story building holding onto these two thin wires. It's just a walk, technically. Nothing's going to happen unless an earthquake or catastrophic gust of wind happens. You're going to be fine as long as you keep your mental state intact. Don't panic. It's just a walk.

In those situations, I look at all the emotions I'm feeling, which are anticipation, exhilaration, focus, confidence, fun, and fear. And then I take fear and say, “Well, how much priority am I going to give this? I really want to do this.” I put it where it belongs. It's like bricklaying or making a stone wall. You fit the pieces together.

To someone who hasn't practiced this, can you suggest an exercise? The next time they’re feeling fear, what would you advise them to do?

I actually want them to partition each emotion as if it's a little separate block and then put the blocks in a line. Once you assess your own skill and the situation, often things change. I hear people say, “I'm so scared of picking up an insect.” Really? What is really so scary about an insect? Is it going to eat you? No.

As long as you stop and really look, I think people's lives will change radically. Women especially are very, very quick to say they’re scared. That's something I really want to change.

You wrote an op-ed in 2016 titled, In one passage, you said that books on female empowerment reach women far too late in their lives. Can you elaborate on that and also explain what caused you to write the op-ed?

I wrote The Gutsy Girl as a sort of antidote for what I see happening now and maybe has happened for a long time, which that we acculturate our girls to be fearful. I was really curious about how that started after I wrote the book, so I looked at some studies. It turns out that parents—both moms and dads—caution their daughters way more than their sons, basically telling them, “Watch out. That's dangerous. You're going to get hurt.” They discourage them from trying something.

With boys, there is active encouragement, despite the possibilities that they could get hurt, as well as guiding the boy to do it, often on his own. When a daughter decides to do something that might have some risk involved, after cautioning her, the parents are much more likely to assist her doing it. What is this telling girls? They're fragile and they need our help. So of course, by the time we're women and in the workplace or relationships, that's going to be a predominant paradigm for us: fear.

What would you say to women thinking, My god. She's totally right. I was raised in a bubble and I don't want to have this default anymore. I want to condition myself to be able to contend with fear and put it in line?

I would say it's time to adopt a paradigm of bravery instead of a paradigm of fear.