I first heard about Gym Jones the way you hear about a secret trout stream or an all-night rave—through word of mouth and friends of friends. To me, gyms tend to come in two varieties, neither particularly appealing. Option A: the Fitness Supercenters, with their overcrowded cardio dens and cucumber-scented saunas. And Option B: the Iron Grottoes, run by mulleted muscleheads in Metallica T-shirts. Gym Jones, the rumor went, was something else entirely, a new type of facility devoted to a mutant strain of fitness that combined elements of powerlifting, gymnastics, endurance sports, and military-style calisthenics. Insiders insisted that this odd hybrid was building bombproof athletes of all types and ages, and that the movement had acquired a devoted following in locales stretching from Washington, D.C., to Vancouver, B.C.

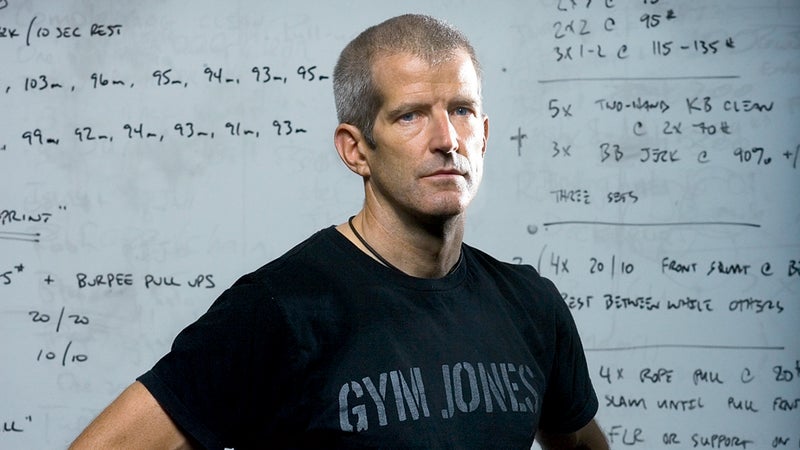

is located in Salt Lake City, where it was created by Mark Twight, a world-class alpinist who chiseled a career on walls of rock and ice so dangerous that, in some instances, he had only about a 50 percent chance of survival. Twight retired from climbing in 2001, at least from the suicidal stuff, and recommitted himself to the art and science of physical conditioning. His expertise attracted an elite cross-section of clients—mountaineers, military special ops, cage fighters—but the gym, the origins of which date back to 2003, remained a largely underground phenomenon until 2007, when Twight had trained the British actors who portrayed Spartan soldiers in the war-porn fantasy film 300. Over the course of a few months, he'd turned the doughy thesbians into a hardened phalanx of freshly waxed Chippendales models, with marbled arms and abs like giant tortoiseshells. The superbods inspired a viral buzz that catapulted traffic on the Gym Jones Web site from a million hits a month to more than 11 million.

Like its owner, the gym took on a mystical, slightly nightmarish quality: part martial-arts dojo, part smash lab, part medieval dungeon, all intended to facilitate the arduous process of mental and physical transformation. When I checked out the Web site, I was greeted by a skull and crossbones and a warning: “Gym Jones is not a cozy place. There are no televisions, no machines, no comfortable spot to sit . Effort and pain may not be avoided. Physical and psychological breakdowns occur.”

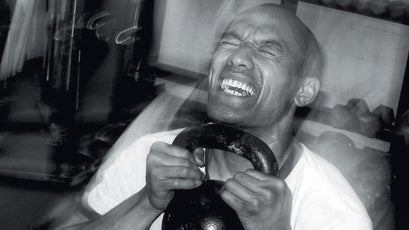

The routines were said to be so intense, so blindingly debilitating, that they brought even the hardest men to their knees, whimpering in slicks of their own sweat. “The first time I went through one of those workouts, my legs swelled up like balloons. I couldn't walk for a week,” says Rob “Maximus” MacDonald, a world-champion mixed-martial-arts fighter who now helps Twight run the gym.

OK, I thought, that which does not kill me and then I e-mailed Twight, asking if I could come out to give it a try. His response was swift and dismissive. Who the hell was I? Did I have any idea what I was getting myself into? “Many of our guys worked out for a year before they started meaningful training,” he wrote. “I'm not interested in having someone take a shallow look . A quick peek is a waste of time.”

I told him I was hoping for more than a quick peek. As a 41-year-old amateur athlete, I was acutely aware of the encroaching infirmities of middle age, but I hardly felt like my days on skis, a bike, or a soccer field were anywhere close to being over. I might be slipping, but I still felt strong and capable. With a little help, I figured, I could unleash whatever whup-ass was left.

Twight agreed to let me attend one of his two-day introductory seminars, provided I came prepared. That meant I had to “pretrain,” so he put me in touch with one of his handpicked disciples, Carolyn Parker, a 39-year-old mountain guide based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, not far from my home.

Once a week for the next two months, I drove to a grassy field where Parker, a stunning physical specimen with a fondness for climbing waterfall ice in designer leather pants, schooled me in “the Gym Jones way.” The first day, she threw a medicine ball so hard that it knocked the wind out of me. Other sessions involved dizzying combinations of dead lifts, squats, lunges, strange ballet-like kettlebell routines, and various other exercises of sadistic invention.

One day, we did something called “30-30s.” Parker giggled maniacally as she handed me two 20-pound dumbbells. She told me to raise them to my shoulders and push them above my head as many times as I could in 30 seconds. Then I had to hold the weights up, arms locked, for 30 more seconds, and repeat until I'd finished four one-minute sets without a rest. By the last set, I could manage only a few reps, my arms noodling while I emitted a snorting sound, like a warthog. At the end, I fell into the grass, soaking wet. Parker stood next to me with her hands on her hips. “I think you're ready,” she said.

And so, like some sad pilgrim seeking redemption through his own suffering, I arrived at an unmarked warehouse in Salt Lake City on a blistering June day, armed with just enough knowledge to stir a deeply nauseating realization: What I was about to experience was really, really going to hurt.

Gym Jones was conceived in a windowless room in a decommissioned bread factory in downtown Salt Lake. The name was bestowed by Twight's wife, Lisa, a martial-arts student who sometimes carries knives hidden in her boots and who told me wryly that she has “a knack for marketing.” Mostly, Twight used the space to train friends and himself. He was still climbing hard enough that he wanted a dedicated space in which to keep in shape, and mainstream facilities didn't cut it.

“We wanted to do stuff they wouldn't put up with,” he says. “Throwing medicine balls, dropping weights on the ground, working genuinely hard, and creating something with our own spirit, especially the music.”

Ah, yes, the music. Few things had fueled Twight's angst-ridden ride as a climber more than punk rock's Sturm und Drang: Sisters of Mercy, the Damned, Skinny Puppy, and a trove of others, spliced together on mix tapes that he blasted into his ears while hacking up some heinous frozen cliff. His 2001 collection of climbing essays, Kiss or Kill: Confessions of a Serial Climber, contains stories with titles cribbed from song lyrics, like “Glitter and Despair” and “House of Pain.” Twight's worldview could be so nihilistic that one friend nicknamed him Dr. Doom.

Twight made money in various ways from sponsorships, from training elite soldiers in alpine fitness and survival techniques, and from serving as a distributor for Grivel, an Italian climbing-gear company. His interest in starting his own gym evolved in part from experiences he'd had with a then-fledgling program called CrossFit, developed by Greg Glassman, now 52, a charismatic former gymnast from Santa Cruz, California, whom everyone simply called Coach.

CrossFit emphasized old-school exercises and movements like squatting, jumping, pulling, pushing, and so on. Glassman had a gym in Santa Cruz but mainly shopped his product through daily workouts posted on , the Web site he launched in 2001. He contended that CrossFit was all most athletes really needed, because it had the remarkable ability to develop strength and endurance simultaneously. It relied on weight-loaded drills combined with “natural movements” performed with grueling intensity. The circuits were christened with colorful names, like Fight Gone Bad, or after Navy SEAL CrossFitters killed in action. Glassman even created a mascot, Pukie the Clown, a Bozo-like character with a cascade of vomit flowing from his mouth.

Twight first tried CrossFit in December 2003, when Glassman invited him to Santa Cruz to attend a certification seminar. He was plenty fit he could run up 2,000 vertical feet in 45 minutes but not compared with other workshop participants. They competed against each other in Fight Gone Bad a three-lap, five-station circuit involving rowing, dead lifts, box jumps, overhead dumbbell presses, and medicine-ball throwing and Twight finished dead last. “There wasn't enough oxygen in the state of California for me,” he said.

Both humiliated and fired up, Twight flung himself into a CrossFit regimen for the next four months, then tested its effectiveness at a Utah ski-mountaineering race called the Powder Keg. He finished in a satisfying 11th place, against a tough field of experts. Convinced that Glassman's style of training was a genuine secret weapon, he became a CrossFit “affiliate” not exactly a franchisee but a booster for the CrossFit mantra.

After a couple of years, however, Twight says he began to grow disillusioned with the program. CrossFit thrived on a regimen of unstructured daily workouts, but Twight discovered that, while this bolstered his overall fitness foundation, it came at a cost in terms of sport-specific performance. Twight soon found that his power output had increased in certain arenas but his long-range endurance had faltered. He noticed the same thing surfacing among his athletes.

“In December 2006, I gave a test to guys who were training with me that I thought was indicative of their progress,” Twight says. “They underperformed to a degree that made me say, OK, everybody's benched for two weeks. I'm gonna go home and figure this out. That's when I realized that we weren't making progress because we weren't planning our training to make progress.” CrossFit, he said, conditioned people for CrossFit. “But the gym is not our sport,” he says. “Everyone here trains for something else.”

Twight recommitted himself to the concept of periodization modulating volume and intensity over the course of multi-month training cycles. “The biggest disappointment with CrossFit came from treating training as competition (stopwatch, posting comments, etc.),” he wrote to me later. “Our intensity declined, form degraded, and our attitude turned negative as shit got hard, because the training was not designed to support athletic performance outside of the gym. Now we build in recovery periods to assure proper intensity and form. We insist on progressively harder intervals (the last should be the fastest). We don't train to failure. We mimic work/rest intervals common to the sport-specific task.”

Twight still relied on CrossFit-style circuits for the foundation-building phase of his training, and when videos of his work on 300 emerged, showing the actors performing the familiar circuits, Coach blew a gasket. Not only had Twight split from the tribe; he was cashing in on his newfound knowledge. Commercially, CrossFit was doing much better than Gym Jones. (It's on track to earn more than $13 million this year. Twight, whose operations remain private, earns roughly $200,000 a year with Gym Jones.) But Coach remained bitter, angered that so much attention followed the film training, and he accused Twight of pilfering copyrighted CrossFit material for his military seminars.

“Here's proof of the authenticity of Mark Twight's program,” Glassman wrote in an e-mail. “Mark was caught stealing my work, re-copyrighting it and selling it to the Navy Gym Jones is an excellent program. I am its author/inventor/developer.”

Twight laughed when I told him this, though he acknowledges using some of the CrossFit teachings. “Is what we do derivative?” he said. “Of course it is. Everything is. C'mon, we're just picking shit up and putting it down. I won't let my personal falling-out alter my respect for what Greg's done and what he's taught me but it wasn't the end-all, be-all. My mistake when I separated was not separating fully enough. I was lazy and I fucked up. But what I do now comes from a lot of places his material, my material, and many others.”

By the time I arrived at the June seminar, Gym Jones had just moved into its fourth and, Twight hoped, last location a 6,000-square-foot garage full of black rubber floor mats, barbells, squat racks, and other torture-chamber accoutrements. As promised, the only mirror was in the bathroom, and the block walls featured just two decorations: an American flag and a sign, cribbed from Fight Club, that read in part, “Every word you read of this useless fine print is another second off your life. Don't you have other things to do? Get out of your apartment. Meet a member of the opposite sex. Stop the excessive shopping and masturbation. Quit your job. Start a fight. Prove you're alive.”

If I wasn't the weakest person there, I was pretty far down in the pecking order. The group included an Ironman triathlete from California; a couple of ski mountaineers from Boulder; a jujitsu fighter from Australia; and a New Orleans based former SWAT commander with a full sleeve of tattoos. A few rows of metal chairs had been set up in front of a whiteboard. I sat in the back near several guys who looked to be more my speed: T.J., a recent college grad who'd come at his parents' urging; John, an engineer and aspiring marathoner from Ontario; and Andy, a paunchy father of two from New York who was trying to get back in shape. Twight, who looked like Sgt. Rock with his jutting chin and shorn, graying hair, passed out three-ring binders, along with a copy of Kiss or Kill. Promptly at nine, we dove in.

The whiteboard session lasted most of the morning, and I tried to absorb it all despite a persistent sense of dread about the looming workouts. At last we retired to the mats and warmed up. Our first circuit was called Tail Pipe. It involves rowing 250 meters on a Concept2 machine as fast as you can while a partner stands in front of you, holding two 53-pound kettlebells at the top of his chest until you finish. As soon as you're done rowing, you switch places until you've done both exercises three times, without a break. I teamed up with Andy, and we grunted through the drill in just over nine minutes. The fittest guys in the class finished in about half that time.

“Why do you call it Tail Pipe?” I asked one of the coaches, still doubled over and wheezing like an asthmatic.

“Because,” he said chirpily, “it's like sucking air out of a car's tailpipe!”

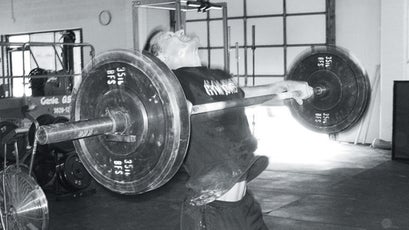

The afternoon wasn't much better. I struggled to complete the Kettlebell Complex a series of awkward lifts and swings and dropped out of Nothing But Pull-Ups altogether. Sunday followed a similar program and, much to my dismay, got even harder, since it involved dead lifts. The dead lift is a straightforward exercise that involves standing in front of a loaded barbell, squatting down, and then hoisting the weight to your thighs. The more weight you add, the more it feels as if your spine is going to splinter like a celery stalk. Lifting twice one's body weight is considered a respectable benchmark. The world record is a little over 1,000 pounds.

I got up to 315, about 85 pounds shy of my double-body-weight fantasy, before throwing in the towel. I had been trading turns with John, the marathoner, who I thought had stopped because he was worried about an old back injury. But then I noticed him walking in circles in the corner of the gym, listening to his iPod, clenching and unclenching his fists. At 45 years old and 158 pounds, John was both the oldest and smallest guy in the class, and everyone gathered around as he fought all the way up to 325 pounds, dropping the bar with a theatrical grunt, followed by a round of cheers. I asked him later what he'd been listening to.

“The Strokes,” he said. “I love music. It gets me so pumped. Before that last lift, I could feel the hairs on my neck standing up.”

The day concluded with the Jones Crawl, a two-exercise ordeal in which you're supposed to dead-lift 115 percent of your body weight ten times, then complete 25 two-footed jumps onto a 24-inch-high box three sets, as fast as you can. Even the tougher seminarians seemed nervous. As we took our places, one of them cried out, “Spartans, prepare for glory!”

I tried to do 200 pounds, but it was too heavy. I barely completed the required ten dead lifts in the first round and had to sit, huffing, before I could contemplate the box jumps. Twight allowed me to reduce the weight, but only slightly. By my second set, I could no longer speak. During my third round of box jumps, I caught my toe and wiped out, raking my shin against the box's wooden edge and removing a strip of flesh. I looked at Twight, who I assumed would let me quit, since a bright red rivulet was now running down my leg. “Bloodsport,” by New Model Army, thundered from the boom box. “Last round,” Twight said, expressionless. “Let's go.”

The whole thing lasted about eight minutes, though it felt like eight days. The only person with a slower time than mine was T.J., the college kid, but he'd lifted more weight.

That night, I staggered back to my room, haunted by a December 2005 story in The New York Times called “Getting Fit, Even If It Kills You,” which dwelled on rhabdomyolysis. “Rhabdo,” as gym rats call it, is a condition brought on when muscle tissue is so severely damaged that it releases myoglobin and other harmful substances into the blood, triggering kidney failure. Rhabdo has been linked to high-voltage electric shock, car accidents, physical torture, drug abuse and, in a few cases, high-intensity workouts.

I was OK, just whipped. Before I finally crawled into bed, I stood shivering in an ice-cold shower, because we were told it would help reduce muscle swelling.

The gut-busting circuits seemed to have served their purpose: By Monday I was so sore I could barely move, and it forced me to contemplate some deep questions: What the hell was this, and why was I doing it anyway?

To be fair, the Gym Jones seminar wasn't simply an opportunity to bathe in the geyser of testosterone that erupts when brawny men gather in a room full of heavy weights. In fact, if anything, I came away from the weekend impressed by Twight's holistic approach, his invocation of restraint, his belief that less really can be more. He encouraged honest self-assessment and rigorous attention to the bigger picture: nutrition, recovery, goal-setting. Of our 20-plus hours in the gym, at least two-thirds had been spent in front of the whiteboard. “I don't want to give a man a fish,” Twight told me afterwards. “I want to teach him to fish.”

There was a lot to learn, not much of it comforting. For starters, my diet was a mess. Beginning my day with a softball-size blueberry muffin and a triple cappuccino, as I'd done for, oh, the past 15 years, apparently didn't cut it. Training was important, but nutrition was the true foundation, because it was the engine of transformation at the molecular level. Twight pushed a Zone-like strategy of roughly equal parts carbs, protein, and fat. The rules were vaguely familiar: more protein, more fiber, more healthy fats like fish oil, and so on; way fewer processed carbohydrates, a daunting challenge when you realize just how much of the American food supply is created from corn and sugar.

“Want to lose weight fast?” Twight said. “Try not drinking alcohol for a month.” These were the facts, he insisted; whether we chose to accept them was up to us.

As fascinating (if discouraging) as I found the dietary discussion, I was even more caught up in the Gym Jones weight-lifting philosophy. Since I was sticking around for a few days, Twight took me to meet Dan John, a strength-training czar who lives in Murray, a suburb of Salt Lake. “Dan is the master of simplification,” Twight said on the drive out. “I've probably learned more from him than nearly any other individual.”

John, 51, runs the Murray Institute for Lifelong Fitness, or, as he likes to call it, MILF. The way Twight talked about it, I expected MILF to occupy some gleaming hilltop campus, but in fact it's shoehorned into John's two-car garage, between his Mazda 6 and a refrigerator full of soda, beer, and bottled water. A rusty squat rack is pushed up against one wall, and two deep furrows have been worn into the concrete floor where the barbell plates repeatedly land. MILF also has an annex, a weedy alley that parallels an irrigation canal behind the house. When John and his jocks aren't swinging kettlebells or performing squats in the garage, they can often be found out back, dragging a weighted sled up and down the dirt lane.

John spent the afternoon sharing his 25 years of accumulated knowledge about strength and performance. Weight lifting, properly deployed, will serve any athlete at any level because it develops power, he told us, and power is the one thing central to almost every sport. Most of what I knew about weight training I'd learned in high school, where I mimicked routines that had originated in competitive bodybuilding. The strategy entailed isolating muscles and working them until they failed curls, bench presses, triceps extensions, etc. and then moving on to the next muscle group. After a while, your muscles got bigger, and, naturally, everyone assumed that a bigger muscle was a stronger muscle.

But that isn't always the case. In fact, exercise physiologists discovered that muscle isolation is often counterproductive when it comes to executing more complex natural movements, where muscles are required to work in concert. Hence the value of Olympic lifting, with its expanded range of motion. Physiologists also discovered that only certain types of lifting make muscles grow larger specifically, doing eight to 15 reps in sets that end in complete exhaustion. In contrast, slightly modified approaches, like fewer reps with heavier weights, build stronger muscles without making them bigger particularly appealing to endurance athletes, for whom increased size is considered a liability.

There's legitimate science behind the high-intensity work, too, and both John and Twight believe that, done right, it produces rapid and profound results. The most convincing studies have been done by a Japanese physiologist named Izumi Tabata. In 1996, Dr. Tabata discovered that short-duration, high-intensity training enhances anaerobic capacity while simultaneously increasing aerobic endurance. This allows you to shed more fat than with moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, and it also produces a metabolic afterburn as the body works to repair itself. Circuits like those we did at Gym Jones are sometimes referred to in the weight-lifting community simply as “Tabatas.”

“Strength is the glass,” John called out as Twight and I walked down the driveway at MILF late that day. “All your other training is the liquid.”

Before I left Utah, I joined Twight for a bike ride. He was training under the guidance of Dr. Massimo Testa, a sports physician whose résumé includes work with Miguel Indurain, Lance Armstrong, and a peloton's worth of other pros. Testa was helping Twight get ready for the Tour of Park City, a 170-mile race with 9,000 feet of elevation gain. I felt slightly ridiculous when Twight showed up on his carbon-fiber rig, decked out in full race kit, since I was winging it on a rented touring bike and wearing hiking shorts, running shoes, and a T-shirt. But anything was better than following him into the dark recesses of his pain cave, even if it meant chasing him around the mountains outside Salt Lake.

Thankfully, this was a recovery day for him, and we spun along a winding canyon road at a pace I could manage. Twight likes to describe himself as a “control enthusiast,” and he told me that, as much as Gym Jones seemed poised for bigger things, he was willing to grow the business only if he could do so without compromise. He'd hired a business coach at the end of 2007 to help him sort out the process, and a few things were already in the works. He planned to increase the number of seminars, which routinely sell out despite costing $1,500 per person, from four to 12 times a year. A set of training DVDs (working title: Unfuck Your Head) was in production. He had six part-time trainers and 30 paying clients and would bring on more as demand warranted. At night, or early in the mornings, he was chipping away at a book, a comprehensive philosophy behind his training methods. And he's currently finishing a dimension of the Web site that will cater exclusively to paying members, who will be able to interact with Twight and other coaches, exchange ideas, and create the kind of virtual community that will mirror the real ones beginning to materialize all around him.

The trickiest part, he said, is communicating the essence of his project. Changing your body is just mechanics; it's changing your mind that presents the real challenge.

“If the mind is not first trained to enjoy hard work, to relish suffering, to address the unknown, then no program, no amount of training can be effective,” he told us during the seminar. “The muscle we are interested in training is inside the skull.”

Twight acknowledges that Gym Jones borrows heavily from CrossFit but also laughs it off.“Is what we do derivative? Of course it is.Everything is.”

For all the clanking iron and sweaty caterwauling, what Twight has created at Gym Jones is not a place where its denizens are guaranteed to succeed but an environment in which they're allowed to fail sometimes catastrophically. “The risk of failure, social or physical, is paramount, because failure and dissatisfaction are the parents of thought,” he said. “Success and fulfillment do not inspire or require introspection.”

We reached the top of a high pass. Twight wanted to keep going down the other side, but I told him I was too spent from the weekend. “Fair enough,” he said as we about-faced.

I wondered if the world is ready for what he has to offer, if people are prepared for such serious commitment. Clearly, at least a few are. No-frills outfits created in the spirit of Gym Jones are beginning to sprout everywhere Mountain Athlete, in Jackson, Project Deliverance, in St. Louis places devoted to helping us endure the kind of flogging that training like this entails. Twight had told me about a young climber from France who'd found out about him on the Web, flown to Salt Lake, slept in a city park, and showed up at Twight's house the next day. No e-mails. No phone calls. “I want to train at Gym Jones,” he told Twight, who was so impressed he invited him to stay for the next three months.

What Twight rails against is mediocrity not in terms of output, but effort and, for him, too much of what fitness has become in America engenders exactly that. He's matured considerably since his days as a tortured alpinist, but he hasn't relinquished his rebellious inner punk, pushing back against so much of what we're told and sold every day. Fitness for him will never be a program, because, by definition, it has to be a perpetual and ever-evolving process individually crafted and constantly reevaluated and revised. “It's easy to be hard, but it's hard to be smart,” he wrote to me, quoting an old Marine saying, but it was cold comfort, since such insight implies that the progression never gets any easier.

Worse, perhaps, was my gathering awareness that I'd bought it. Gym Jones had introduced me to the whole picture: How to create a rock-solid foundation and how to build off that to achieve my specific athletic goals. What that might be I wasn't quite sure, but I'd lost five pounds since I started training with Carolyn Parker, and despite the beating I'd taken in Salt Lake, I already felt stronger. I realized I'd drunk generously from Twight's rancid punch and, in a strange, masochistic way, looked forward to returning to the grassy field in Albuquerque, where Parker would continue doling out the punishment.

I tried to keep Twight in sight as we descended, whooshing past a few other cyclists grimacing through their long grind up the canyon. I couldn't remember the last time I'd gone so fast on a bike, and it was exhilarating and terrifying at once hunched over the handlebars, swooping around the switchbacks, hurtling toward a future in which I imagined that what we were doing and what we were capable of doing had somehow, suddenly, become the same thing.