MAYBE YOU’RE PRETTY FAST on a bike—speedy enough to entertain hopes of winning a district championship with the help of a training regimen borrowed from Lance & Co. You’ve got a heart-rate monitor, and you spent last winter grinding through long, slow, base-training rides, thinking that this would prepare your cardiovascular system for intense summer efforts. But as you plowed through freezing rain, did you ever second-guess your methods?

Programmed to hammer: debug your mind and your muscles will follow.

Programmed to hammer: debug your mind and your muscles will follow. Illustration by Aaron Meshon

Illustration by Aaron Meshon Illustration by Aaron Meshon

Illustration by Aaron Meshon

You should have. There’s another way to reach peak shape. It’s called neuromuscular training, and it can have you ready for a century ride or a triathlon in as little as six weeks. Cutting-edge fitness research has uncovered a network connection between your brain, your muscles, and your athletic performance, and the findings are a boon to time-strapped endurance athletes pushing for personal bests.

“Strength is speed-specific,” says Owen Anderson, running coach, exercise physiologist, and editor of Running Research News, a newsletter that covers the sport’s most recent theories. “If you’re training slowly, you’ll be strong at those slow speeds, but not at the higher speeds you need to compete. If you want to be a faster athlete, it’s crazy to practice being a slow one.” The 56-year-old Anderson is a leading member of a tiny but growing faction of coaches and world-class athletes focused on exploiting the unconscious link between your brain and your muscles. The former tells the latter what to do: Program the right pace, and, according to the neuromuscular fitness philosophy, you’ll run, bike, or swim as quickly as you’ve conditioned yourself to go.

For neuromuscular training, two things matter: one, that you work out at the level at which you plan to compete, and two, that you teach your brain to anticipate—and work through—the burning in your muscles that accompanies intense effort. The payoff is much less time spent achieving a competitive level of fitness. How much time will you save? Try months.

Case in point: Mark Carroll, a 31-year-old Irish middle-distance running champion who finished sixth in last year’s New York City Marathon, his first 26.2-mile event. He credits his performance to an 11-week regimen of targeted race-pace training, which he picked up from Anderson’s July 2001 article in the British newsletter Peak Performance. For the marathon, Carroll focused on 20-mile runs every other week, with shorter runs in between, all completed at, or seconds off, his eventual race pace of five-minute miles.

“Most runners train really long and slow,” Carroll says of the six-month training schedules maintained by some elite marathoners, “but it’s junk.”

“Think about your goals,” advises Anderson. “If you’re training for a 25-mile time trial on a bike, train at that distance, train that intensity, so that your neuromuscular system will know exactly what to expect.”

It’s an idea already embraced by many Olympic-level athletes, according to Jon Schriner, medical director of the Michigan Center for Athletic Medicine. “It just hasn’t trickled down to everyone else yet,” he says.

Before you go from 5K runner to marathoner lickety-split, you’ll have to address the second tenet of neuromuscular training: teaching your mind to push through pain, because—we won’t lie to you—there’s a lot of it. Your goal is to channel the toughness of an athlete like Lance Armstrong, who’s legendary for tolerating quad-searing efforts more stoically than any cyclist in the world.

“When your brain registers fatigue as a sensation, you typically make a subconscious decision to slow down,” says Tim Noakes, a professor of sports science at the University of Cape Town, in South Africa, who’s researching the relationship between the brain and athletic performance. “Our studies show that your muscles aren’t as tired as you think.”

IN ONE STUDY, Noakes, 54, put athletes on stationary bicycles in a climate-controlled room to test the brain’s response to temperature. If the room was hot, within five minutes cyclists dropped to a pace slower than they could maintain if the room was cold, even though their muscles hadn’t registered any change in temperature. It wasn’t muscle fatigue, dehydration, or any other physiological factor slowing them down. It was their brains thinking they couldn’t pedal fast because of the heat. In other words, if you train your brain to allow your body to go faster, farther, or both, it will.

Not surprisingly, neuromuscular training as a shortcut to race-ready fitness faces a skeptical audience of pro athletes and coaches who thrive on a base-training regimen. Cycling coach Rick Crawford, 44, instructs his riders, including Tour de France contender Levi Leipheimer, to spend up to three months each winter riding as many as 30 hours per week, while maintaining sweat-free heart rates that fall below 70 percent of their capacity.

“It’s absolutely essential,” says Crawford, who, like other base-training advocates, believes low-intensity miles are essential to increase the delivery of blood to your muscles. And the more oxygen-rich blood your body delivers to a muscle, the harder it can work.

Crawford doesn’t think neuromuscular training is wrong; he just doesn’t think it’s right for pros or serious amateurs who compete every week for six to nine months a year, instead of once or twice. “I could use neuromuscular training to bring my athletes to form in six weeks,” he says, “but what am I doing to ’em the rest of the year? They’re toast.”

Crawford’s concern is legitimate. Intense neuromuscular training at race distances can’t be sustained for weeks at a time. It needs to be completed in six- to eight-week cycles that start with low mileage and build up to specific competitions (see “,” next page). Otherwise you risk overtaxing your body.

Neuromuscular training takes time and practice—your body still needs several weeks to develop the strength and endurance to last—but for the off-and-on competitor, it’s a valid method for becoming race-fit faster. “Training time is so precious,” says Owen Anderson. “Knowing that, why would you waste it on workouts that aren’t going to make you more competitive?”

Race-Ready in 41 Days Trainer Owen Anderson designed the following program for runners attending his neuromuscular camps, but it’s valid for cyclists, swimmers, and other endurance athletes. Anderson’s plan assumes that you’re already devoting four to six hours a week to cardiovascular exercise. (If not, spend six weeks building up your fitness level before you jump into this high-intensity training.) Make sure to start each day’s workout with a ten-minute warm-up at a conversational pace, followed by a sport-specific neuromuscular exercise (see “,” next page). End each session with a ten-minute cooldown.

Jump-Starters Before you strike out at race pace for a run or ride, you need to spark the brain-brawn connection. After a ten-minute warm-up, complete the following exercises, courtesy of physiologist Owen Anderson.

For Cyclists

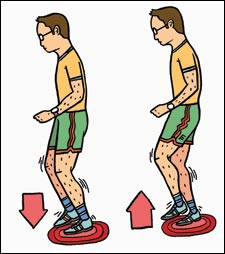

Bicycle Leg Swings: With a wall to your right, at arm’s length, stand on your left leg and place your right hand on the wall to maintain balance. (1) Kick your right leg forward, so that your thigh is at waist level and your leg is fully extended. (2) Swing your leg backward and extend it behind you. (3) Now bend your right knee, snapping your heel toward your butt while bringing your right leg forward in the same motion, then kick out to full extension once again (fig. 1). Complete the sequence 45 times in 30 seconds with each leg. Repeat.

For Runners

Standing Acceleration: Jog in place for 15 seconds, then dramat-ically increase your cadence, pumping your legs as fast as you can for 20 seconds. Try to minimize foot contact with the ground and work on maintaining an upright posture. Complete three sets.