Peak performance happens as a result of trying really hard, and then not trying at all. It’s a paradox. I’ve never met someone who has described a breakthrough performance as effortful or straining or tight. It’s the opposite: when people are at their best—whether it’s on the playing field, in the workplace, or in the artist’s studio—they report feeling loose, relaxed, and at ease. They aren’t thinking and they certainly aren’t trying. They are effortlessly flowing, one action leading to the next, completely immersed in what they are doing, in the zone.

In the 1970s, a psychologist named coined this state of optimal performance as flow. Flow is most likely to occur when as little as possible gets between an actor and his or her act. That’s why a is feeling as if you’re at one with what you’re doing. The less that gets in the way—doubt, worry, planning, wearable devices—the better.

Unfortunately, you can’t just pick up an activity and decide to get into flow. Even something as simple as running requires a learning period during which you’ve got to put forth effort and try. You’ve got to make things happen before you can let them happen.

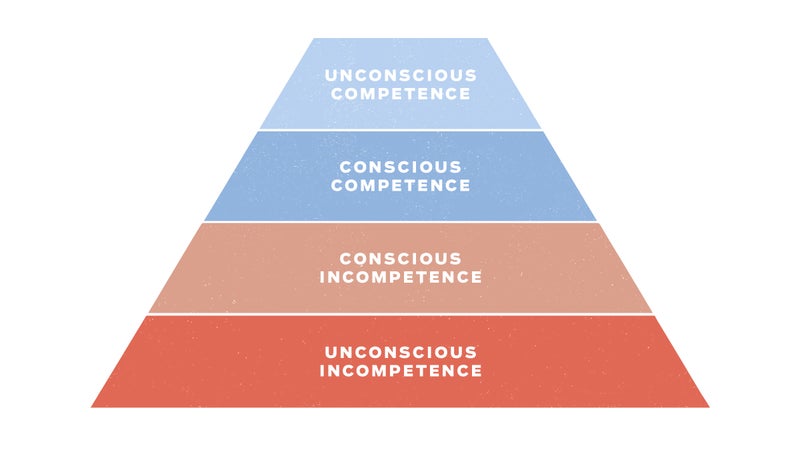

A model of human development called the four phases of competence captures this progression quite well. Developed in the 1970s by an employee of the , this model suggests that individuals advance from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence, to conscious competence, to unconscious competence. The endgame may be a total release from trying—flow—but you’ve got to work your way there.

Unconscious incompetence is what most of us experience when we are brand-new to something. We don’t know what we’re doing, and we don’t know that we don’t know what we’re doing. At this stage, the focus should be on humility and learning the basics. We’ve got to get our bearings before we can get moving.

Conscious incompetence is when you’re making mistakes but you’re aware that you’re making mistakes. During this phase, thinking, analyzing, and trying is the very stuff that allows you to move forward.

From there you progress to conscious competence: you’re doing whatever it is you are doing correctly, but not without effort. You rely upon your thinking mind and moment-by-moment feedback. During this phase, wearable devices and data are extremely useful. They provide confirmation that you’re on the right track, and they alert you when you’re not so that you can course correct. You’re trying superhard and finally getting it right! This is a great feeling. This is also the juncture, however, where most people get stuck.

That’s because in order to progress to the peak phase of development, to unconscious competence—to flow—you’ve got to release from thinking and trying and just settle in. This requires shedding all the trying that got you so far. Here is where you ditch the GPS watch and heart-rate monitor and all the pressure you put on yourself to succeed. All the stuff that helped you along the way—both physical and psychological—now becomes baggage, the barrier between you and the direct experience of whatever you’re doing, the barrier between being good and being great.

shows that individuals who enter flow states have progressed through the four phases of competence. What’s interesting to me is that in this current moment there is so much technology marketed to help people achieve peak performance, and yet it’s this very technology, and all the thinking and trying that comes with it, that often gets in the way! The solution would be easy if this technology served no purpose—you’d just do away with it. But generally speaking, the technology does serve a purpose. It’s instrumental in helping people move from unconscious incompetence to conscious competence. It works great. Until it doesn’t.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to know when you’re ready to release your grip on trying and settle into flow. But one of the best cues is when you’ve been performing well—but not great—for a few months and, at the same time, you’re getting tired of trying, when what was once exciting and expansive starts to feel tedious and constricting. This is a sign that the time is right to release. And it is only then, when you let go of the very thing that has got you so far, that you open up to your best performance.

Brad Stulberg () is a performance coach and writes ���ܳٲ������’s Do It Better column. He is the author of the bestselling book and .