By the time Ben Boyer hit 40, he was falling apart. A former college athlete, he spent decades pushing his body in the weight room and felt those years of abuse in his knees. “I was hobbling around,” says Boyer, who lives near Jacksonville, Florida. “On a pain scale of one to ten, I was at four to six every day.”

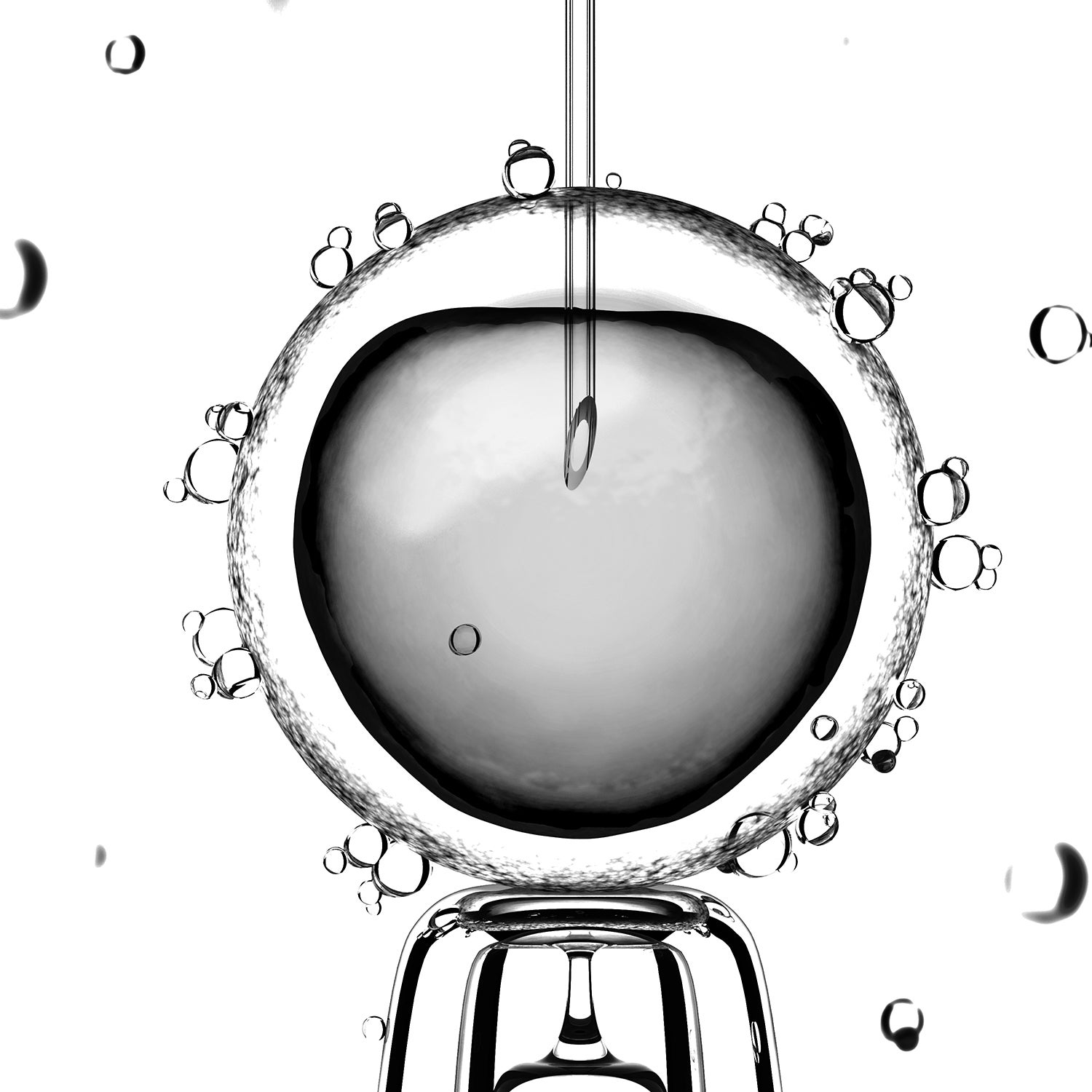

Boyer had already undergone knee surgery to repair tendon and cartilage damage, and he wasn’t interested in repeating the procedure, nor the lengthy recovery time that followed. He also didn’t want to spend the rest of his life on pain medicine. So he turned to stem-cell therapy, in which cells were taken from bone marrow in his pelvis and injected into his knees in hopes of relieving his arthritic aches.

“Two days after the procedure, I didn’t have any pain,” Boyer says. “I thought it might just be the fluid they injected into my joints, but the pain never came back.” That was three years ago. “It’s been life changing,” he says.

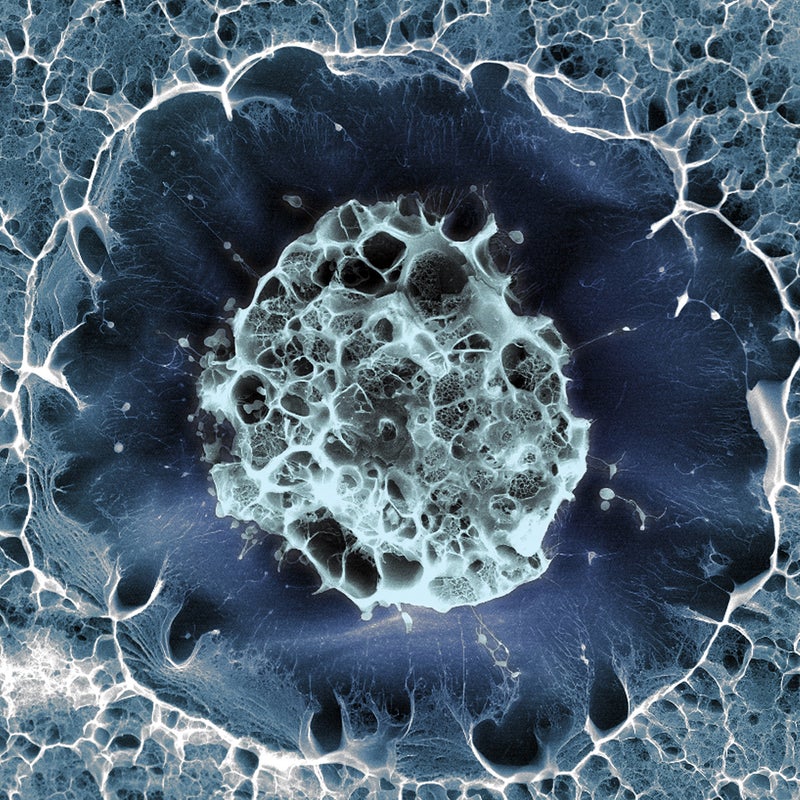

Stem cells are the body’s building blocks, found in blood, fat, and bone marrow. They have the ability to generate new cell types that can be used to repair or replace damaged tissue, which has long excited researchers interested in their medical potential. For years, professional athletes have been seeking out stem-cell injections for injuries, but only recently have they been visiting U.S. clinics in large numbers. Previously, it was easier to visit clinics overseas, where regulations can be less rigid. In South Korea, for instance, the process for green-lighting new therapies is more streamlined—or lax, say critics—and has led to the approval of certain procedures, including those involving the manipulation of stem cells after harvesting, without extensive clinical trials or peer review.

In the U.S., when stem cells are manipulated, or when their original function changes after being injected into a patient, they must be classified as drugs. That means rigorous trials and a lengthy FDA approval process are required before the treatments are legally available. Still, as interest in stem-cell therapy has grown among weekend warriors and baby boomers, hundreds of clinics have opened. Many are following FDA guidelines. Others, however, defy the rules and promote untested therapies. The FDA recently issued warnings to facilities in Florida and California for allegedly offering illegal stem-cell treatments. In a statement issued in August, the agency promised to crack down on “unscrupulous” clinics making “hollow claims” and marketing “unsafe science.” But considering the sheer number of facilities now providing stem-cell therapies of one kind or another, regulatory enforcement is likely to be challenging.

Leigh Turner, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota’s , estimates that at least half of the nation’s existing stem-cell clinics could be offering untested therapies. “Some of these clinics are making outrageous marketing claims,” he says, noting that there are plenty of case studies to support the enthusiasm in the burgeoning stem-cell field but not enough hard data from clinical trials. Physicians promising to, say, cure macular degeneration or repair a torn tendon or relieve arthritis are taking an ethical leap. “It’s like the Wild West right now,” says Shane Shapiro, a program director at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville.

That’s not to say that all stem-cell therapies are suspect. Over the past decade, countless clinical trials have shown that stem-cell injections can reduce scarring and regrow muscle tissue in heart-attack patients. Stem-cell products designed to treat cardiac failure have already been approved in South Korea, and advanced trials are under way in the U.S. and Europe.

In 2014, Shapiro conducted the first orthopedic stem-cell trial of its kind to meet FDA standards. Boyer, the former college athlete, was among 25 patients with degenerative pain in both knees to be given a stem-cell injection in one and a saline solution in the other. The results, last January, are both promising and puzzling. Not only did the knee that received the stem cells improve for each patient, but so did the knee that received the saline. Just like Boyer, many of the participants are still pain-free.

“A lot of patients are getting better from this, and we’re excited, but we don’t yet know why,” Shapiro says. “We have to design better studies and replicate them. We can’t just be applying the medicine without knowing if it actually works.”

That kind of caution is often hard for patients to understand. It’s no surprise, then, that many aging athletes are seeking treatments despite the lack of sufficient evidence to support their effectiveness. Turner’s advice: find a clinic that’s working with the FDA on a clinical trial; such trials are often free and are monitored for safety. “Complications do arise from untested therapies,” he says, “but the more likely scenario is that a patient will spend $10,000 hoping for a miracle and the procedure won’t help at all.”

In other words, stem cells might be the future of orthopedic medicine, but right now? Caveat emptor. “There’s real potential in this medicine. We’re just not there yet,” says Scott Rodeo, an attending orthopedic surgeon at the in New York City. “The marketing is ahead of the science.”