If endurance athletes tend to have a streak of what sports scientist calls “benign masochism,” then the whole foam roller thing makes a lot of sense. It’s right up there with ice baths in terms of (a) unpleasantness and (b) fanatical devotion from athletes. I have multiple family members who’ve shown up to my house for weekend visits with a foam roller in their carry-on bags. It’s apparently more important than a change of underwear.

For the uninitiated, foam rollers are large cylinders made of fairly stiff foam. I first started to hear about them about 20 years ago as a treatment for iliotibial band syndrome: you lie down sideways with your whole bodyweight pressing down on the roller, then cantilever yourself back and forth to move the roller along the length of your upper leg. The goal is—well, I was never entirely clear on the exact goal. But my first one came with a modeled by Michael Stember, the Stanford Olympic miler (and now ), so I knew it was legit.

It’s only over the last four or five years that studies exploring the use of foam rollers have started to appear regularly, and most of those studies have been too small to draw firm conclusions from. So in the journal Frontiers in Physiology, from a research team at Ruhr University in Germany, is overdue: it’s a meta-analysis of 21 different studies on foam rollers and the closely related self-massage devices. Fourteen of the studies used rollers as part of a warm-up and tested their effects on things like sprint and jump performance and flexibility; the other seven used rollers post-exercise to investigate their effects on recovery.

So what exactly is the roller supposed to do? It’s basically a form of self-massage, the authors of the review explain. And that means… a lot of things. “[T]he potential effects of [foam rolling] have been attributed to mechanical, neurological, physiological, and psychophysiological parameters,” they write. In other words, it could be reducing tissue adhesions, or activating mechanoreceptors, or increasing blood flow, or triggering endorphins, or a long list of other potential mechanisms that are floated, without any particular supporting evidence, in the reviewed articles. The last item on the list is “and/or placebo effect.” We’ll come back to that, but the bottom line is that people foam roll because it feels good (or feels bad in a good way), not because we have any compelling physiological evidence that it should do something.

When you’ve got a bunch of studies that each test slightly different things in slightly different ways, it’s hard to sum them all up succinctly. The general trend was mildly positive results: a 0.7 percent improvement in sprint performance and 4.0 percent improvement in flexibility after pre-workout rolling, for example; and similar benefits in maintaining sprint and strength performance after post-workout rolling. On the surface, that seems like good news. But it’s worth taking a closer look.

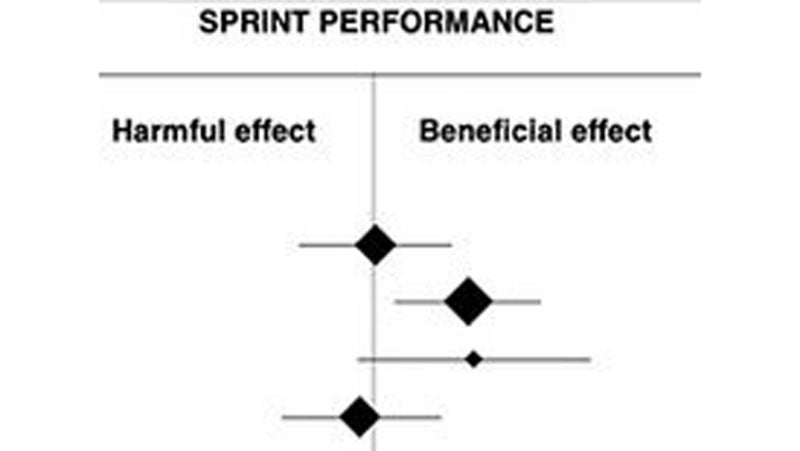

Take, for example, the apparent improvement in sprint performance, which has one of the largest effect sizes of any outcome measure. While the overall meta-analysis involves 21 studies, only four of them measured sprint performance after pre-rolling. Here’s what those four studies look like in a “forest plot,” in which each study is represented by a single diamond. Those to the right of the center line indicate that foam rolling made the subjects faster on average, while those to the left made them slower; the size of the diamond is proportional to the number of subjects in the study.

Of the four studies, two of them found essentially no effect, while one very small study found a positive effect that’s not significantly different from zero. So the conclusion that foam rolling boosts sprint performance is almost entirely based on a single study that disagrees with two others.

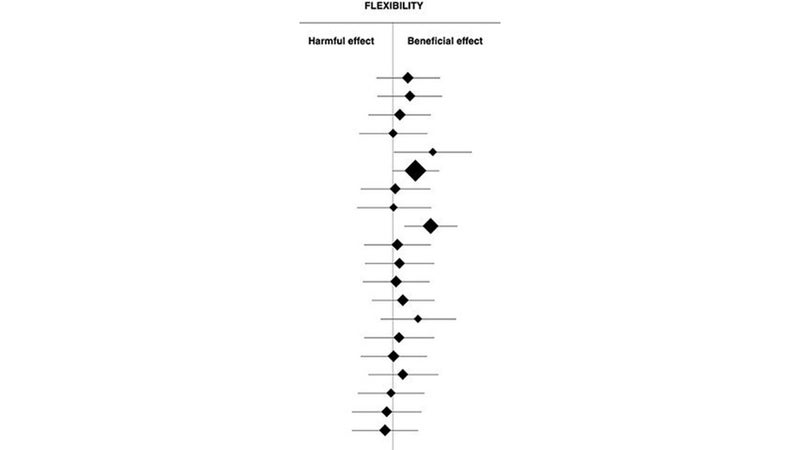

Some of the other findings are a little more robust. For example, here’s the forest plot for flexibility after pre-rolling:

In this case, there are a bunch of studies which tend, on average, to have mildly positive but not statistically significant results. Aggregate the data, and you have a nice clear 4.0 percent improvement in flexibility that is statistically significant. That’s the whole point of meta-analyses: combining a bunch of small studies into one big pseudo-study. There’s still a fly in the ointment, though, which is that it’s pretty much impossible to run a blinded study of foam rollers. Everyone knows if they’ve been rolled, and that may set expectations for performance—and some outcomes, like flexibility, may be particularly susceptible to placebo effects.

The authors of the meta-analysis deal with this uncertainty by hedging their bets. “Overall,” they write in the abstract, “[…] the effects of foam rolling on performance and recovery are rather minor and partly negligible.” But in the next sentence, they say that “evidence seems to justify the widespread use of foam rolling as a warm-up activity.” In the discussion, they note that for elite sprinters, an improvement of 0.3 percent could be significant—so even “minor and partly negligible” boosts may be worth pursuing.

My own conclusion after wading through the meta-analysis is basically a big shrug. If someone showed me this data and told me it was based on an exciting new pill, I’d tell them not to waste their money on the pill. It’s not convincing enough to win new believers. But neither is it damning enough to conclude that athletes definitely shouldn’t use foam rollers. The roller fans I know tend to use it as part of a stretching routine, but they’re not necessarily looking for an increase in maximum range of motion. Instead, it helps them feel loose within their normal range of motion—a subjective benefit that’s much harder to study and quantify. For now, I think that’s pretty much the best we can do: foam rollers apparently worked for Michael Stember, and they might work for you, but science doesn’t have much to say one way or the other about them.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the .