Athletes have a very complicated relationship with pain. For endurance athletes in particular, pain is an absolutely non-negotiable element of their competitive experience. You fear it, but you also embrace it. And then you try to understand it.

But pain isn’t like heart rate or lactate levels—things you can measure and meaningfully compare from one session to the next. Every painful experience is different, and the factors that contribute to those differences seem to be endless. in the Journal of Sports Sciences, from researchers in Iraq, Australia, and Britain, adds a new one to the list: viewing images of athletes in pain right before a cycling test led to higher pain ratings and worse performance than viewing images of athletes enjoying themselves.

That finding is reminiscent of a result I wrote about last year, in which subjects who were told that exercise increases pain perception experienced greater pain, while those told that exercise decreases pain perception experienced less pain. In that case, the researchers were studying pain perception after exercise rather than during it, trying to understand a phenomenon called exercise-induced hypoalgesia (which just means that you experience less pain after exercise).

This phenomenon has been studied for more than 40 years: one of the first attempts to unravel it was published in 1979 under the title “,” in which an Australian researcher named Garry Egger did a series of 15 runs over six months after being injected with either an opioid blocker called naloxone or a placebo. Running did indeed increase his pain threshold, but naloxone didn’t seem to make any difference, suggesting that endorphins—the body’s own opioids—weren’t responsible for the effect. (Subsequent research has been plentiful but not very conclusive, and it’s that both opioid and other mechanisms are responsible.)

But the very nature of pain—the fact that seeing an image of pain or being told that something will be painful can alter the pain you feel—makes it extremely tricky to study. If you put someone through a painful experiment twice, their experience the first time will inevitably color their perceptions the second time. As a result, according to the authors of another new study, the only results you can really trust are from randomized trials in which the effects of exercise on pain are compared to the results of the same sequence of tests with no exercise—a standard that excludes much of the existing research.

The new study, by Michael Wewege and Matthew Jones of the University of New South Wales, is a meta-analysis that sets out to determine whether exercise-induced hypoalgesia is a real thing, and if so, what sorts of exercise induce it, and in whom. While there have been several previous meta-analyses on this topic, this one was restricted to randomized controlled trials, which meant that just 13 studies from the initial pool of 350 were included.

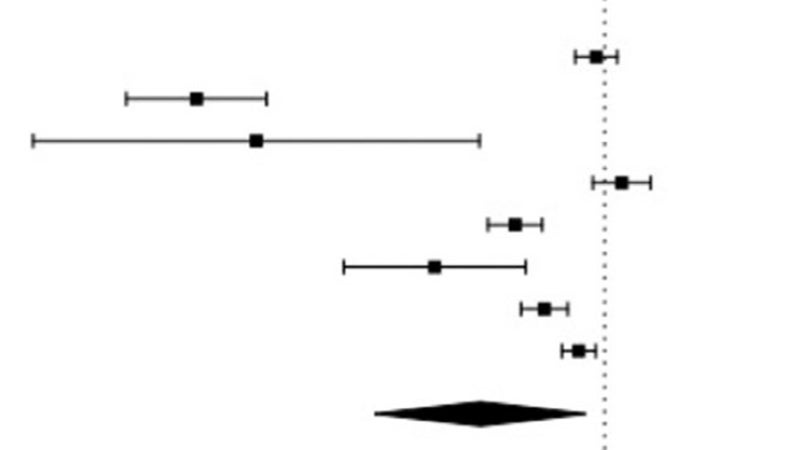

The good news is that, in healthy subjects, aerobic exercise did indeed seem to cause a large increase in pain threshold. Here’s a forest plot, in which dots to the left of the line indicate that an individual study saw increased pain tolerance after aerobic exercise, while dots to the right indicate that pain tolerance worsened.

The big diamond at the bottom is the overall combination of the data from those studies. It’s interesting to look at a few of the individual studies. The first dot at the top, for example, saw basically no change from a six-minute walk. The second and third dots, with the most positive results, involved 30 minutes of cycling and 40 minutes of treadmill running, respectively. The dosage probably matters, but there’s not enough data to draw definitive conclusions.

After that, things get a little tricker. Dynamic resistance exercise (standard weight-room stuff, for the most part) seems to have a small positive effect, but that’s based on just two studies. Isometric exercises (i.e. pushing or pulling without moving, or holding a static position), based on three studies, have no clear effect.

There are also three studies that look at subjects with chronic pain. This is where researchers are really hoping to see effects, because it’s very challenging to find ways of managing ongoing pain, especially now that the downsides of long-term opioid use are better understood. In this case, the subjects had knee osteoarthritis, plantar fasciitis, or tennis elbow, and neither dynamic nor isometric exercises seemed to help. There were no studies—or at least none that met the criteria for this analysis—that tried aerobic exercise for patients with chronic pain.

The main takeaway, for me, is how little we really know for sure about the relationship between exercise and pain perception. It seems likely that the feeling of dulled pain that follows a good run is real (and thus that you shouldn’t conclude that your minor injury has really been healed just because it feels okay when you finish). Exactly why this happens, what’s required to trigger it, and who can benefit from it remains unclear. But if you’ve got a race or a big workout coming up, based on the study with pain imagery, I’d suggest not thinking about it too much.

Hat tip to Chris Yates for additional research. For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .