There are two parallel agendas in a new paper from the science team at Supersapiens, the company promoting continuous glucose monitors for endurance athletes. The obvious one is to unravel some of the mysteries surrounding rebound hypoglycemia, a plunge in blood sugar that afflicts some people when they eat too close to a workout. The underlying one is to show that sticking CGMs, which were initially developed as medical devices for managing diabetes, on thousands of perfectly healthy athletes yields some useful insights that we wouldn’t be able to obtain otherwise. Both goals are interesting—at least to me, given that I’ve experienced occasional bouts of rebound hypoglycemia for as long as I can remember.

The initial pitch from Supersapiens was that a CGM could function as a “real-time fuel gauge” to track levels of glucose (i.e. sugar) in the bloodstream. I dug into the details of this claim in this 2021 article, but the key point is that glucose levels are way more complicated than the gas dial in your car. Exercise burns glucose, but triggers the liver to dump more into circulation. Eating carbs raises glucose levels, but triggers insulin that moves glucose back out of the bloodstream and into muscle and fat cells for storage. There are a whole bunch of signals and countersignals attempting to keep roughly a teaspoon of glucose in circulation at all times.

Sometimes those signals get crossed. If you eat a bowl of oatmeal in the morning, . In response, you’ll secrete insulin to get the levels back to normal. But the insulin spike doesn’t take effect immediately; it won’t peak for 45 to 60 minutes. Meanwhile, if you head out for a run, your muscles will start burning through glucose as much as 100 times faster than they do at rest. If you time it badly, the insulin will kick in just as your muscles start demanding more glucose, and the two effects together will cause your levels to overshoot and produce a blood-sugar low. That rebound hypoglycemia (or reactive hypoglycemia, as it’s also known) can make you feel dizzy, light-headed, and weak.

The typical advice for dealing with rebound hypoglycemia is to avoid eating between about 30 and 90 minutes before exercise, and particularly to avoid high-carb and high-glycemic-index foods. Supersapiens makes the app used with Abbott’s Libre Sense Glucose Sport Biosensor, so it has access to a big database of anonymized data collected by its users. This is a pretty rare trove, because scientists in the pre-CGM era didn’t spend a lot of time measuring glucose levels in people without diabetes. When I spoke to some of Supersapiens’ scientists back in 2021, they were struggling to define what sorts of glucose readings should be considered red flags, because no one was entirely sure what was normal for endurance athletes. The new study, by a team led by Andrea Zignoli of Supersapiens and the University of Trento in Italy, is basically a proof of principle showing that this massive database has some worthwhile lessons to teach us.

The study itself is fairly straightforward. They analyzed almost 49,000 events from 6,700 users in which someone ate something and then exercised. The key variables were how long before exercise they ate, and whether their glucose levels dipped below 70 mg/dL during the first 30 minutes of exercise. This is an arbitrary threshold for rebound hypoglycemia, and in fact there doesn’t seem to be a consistent threshold that produces negative symptoms in different people. Scientists aren’t even sure whether it’s the absolute level of glucose that matters, or the rate at which it’s dropping, or some other combination. But 70 mg/dL is a reasonable benchmark that indicates that your blood sugar levels dropped significantly more than you’d expect.

The first question they considered is how prevalent rebound hypoglycemia is. This is a tricky one to quantify, because almost everyone gets low blood sugar during workouts occasionally (even if they don’t experience symptoms), and no one gets it every time they work out. If you experience it in more than 20 percent of your workouts, it’s probably fair to say that you’re susceptible to it. About 15 percent of the Supersapiens users met this threshold.

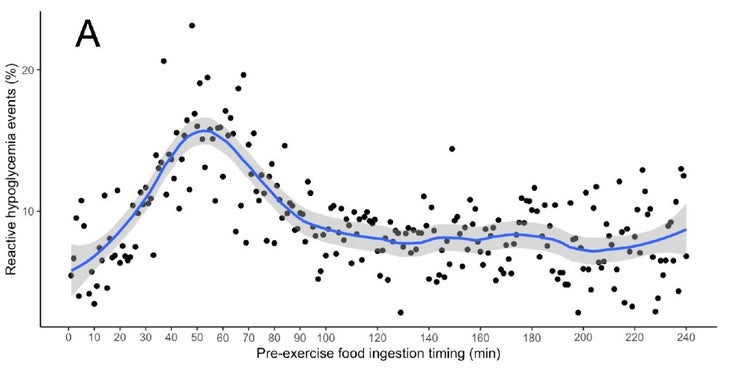

As for meal timing, here’s a graph that shows what proportion of workouts produced a blood-sugar low (on the vertical axis), as a function of time since the last meal (on the horizontal axis):

There’s a pretty obvious bump there, peaking at about 50 minutes before the workout. That’s when you’re most likely to give yourself rebound hypoglycemia, and the risk is higher for the entire period between about 30 and 90 minutes prior.

So there it is! Big data from a whole bunch of CGM users shows us what we already kind of knew. To be fair, they do some further data-crunching. By their calculations, around 86 percent of people aren’t susceptible to rebound hypoglycemia at all. Eight percent are susceptible, but can minimize their risk by adjusting the timing of their pre-workout meal. And the last six percent are susceptible, but meal timing doesn’t seem to make a difference for them. That’s a useful, if depressing, new insight for those who happen to fall into the last group.

As for the bigger picture—the idea that we’ll learn useful things by having endurance athletes wear CGMs—it’s far from a slam dunk, but I think this is a good start. There’s a long, long list of sports science gadgets that can plausibly claim that they might give us useful information. But very few of them follow through with the hard slogging required to validate those claims. Confirming that there’s a pre-workout meal-timing window for rebound hypoglycemia doesn’t really move the needle, and to get deeper insights Supersapiens is going to have to convince a subset of its users to keep really accurate meal and workout records. It won’t be easy, but I’m already curious to see what they’ll come up with next.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .