�����������DzԲԴDZ���

Climber on top of the world

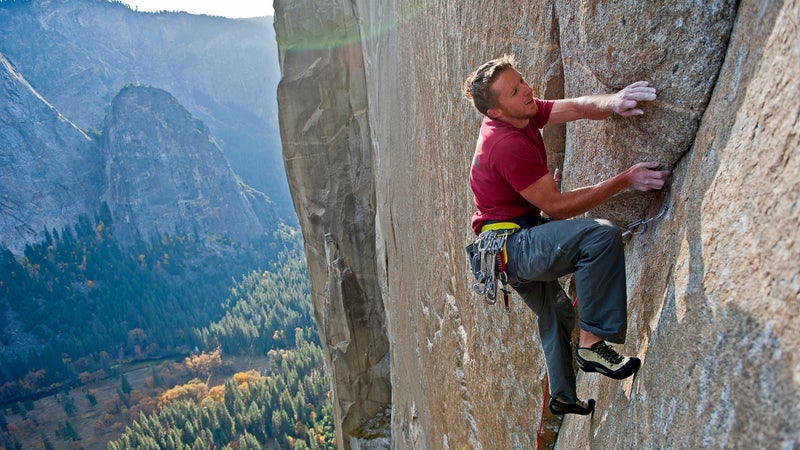

He was already the poster boy of adventure sports coming into 2018, thanks to his free-solo climbs—alone, with no ropes—of massive rock walls. Over the past half-dozen years, his calm embrace of extraordinary risk has garnered a steady flow of mainstream media coverage (, , ) and attracted big-ticket sponsors (BMW, Citibank, Squarespace) while leaving elite climbers dumbfounded. All that was before the October release of , a film that marks the end of his transformation from an unknown dirt bag living in a van to a bonafide superstar who, well, still lives in a van, at least for most of the year.

Back in June, Honnold reminded us that he does know how to use a rope when he teamed up with Tommy Caldwell, of Dawn Wall fame, to break climbing’s equivalent of the two-hour marathon barrier. Honnold and Caldwell sprinted up the storied Nose route on El Capitan in an astonishing 1:58, more than 20 minutes faster than the previous best time. When I spoke to Honnold shortly after they reached the top, he described the record as “totally adequate”—which is exactly the kind of shrugging diffidence we’ve come to expect from the guy. He’s been in the spotlight for almost a decade but rarely says anything that would help us truly understand him. “I separate me the human from me the public persona,” he says. “I’ve had success with that.”

He did, that is, until Free Solo. The 97-minute biopic chronicles his mind-bending 2017 ascent of the 3,000-foot Freerider route on El Capitan. Codirected by husband-wife team Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, whose previous project, 2015’s , was on most short lists for an Oscar documentary nomination, the film offers the first truly penetrating look at Honnold. We see him climbing like a machine, but also losing his nerve and bailing from an earlier attempt of Freerider, and expressing his feelings for his girlfriend, Sanni McCandless. Free Solo, he explains, captures him as accurately as a movie can. “It’s basically me,” he says.

Despite having his real self finally exposed, Honnold still struggles to explain how he’s navigated his wild journey. Which is why, after asking him to share some of the lessons he’s learned along the way, we had the people who know him best add some illuminating commentary. —Matt Skenazy

“The first time I tried to solo Freerider, I climbed up partway and then backed off. I was up there and it felt really scary. I didn’t want to be there. With soloing, it’s important to listen to those signals and then act on them. If I’m not having a good time, there’s no real reason to be doing it.”

“When Alex began the process of documenting his climb for Free Solo, I found it pretty disconcerting. He’d be lying to himself if he said he didn’t like the glory and attention that comes from being the world’s boldest climber, and my concern was that having a camera crew around would muddy his judgment. In the end, I made peace with the fact that this was the magnum opus of his whole weird art-slash-career.” —Cedar Wright, climbing partner

“My mom taught me how to drive. One day when I was stressed in traffic, she said, ‘If you’re ever really worried, you can just park. Just stop and get out. People will go around.’ That’s a great life lesson: you can always just stop.”

“There was this time when we were both young and I had my license but Alex didn’t, and I was letting him drive to practice. He made a right-hand turn too sharply, and the minivan went up on the curb. We were about to hit a telephone pole. Alex very calmly stopped and let the rest of the traffic go by. Mom would have been proud.” —Stasia Honnold, sister

“[Laughs] Alex never parks. And where did he come up with this? It’s probably something his mom wrote in her new memoir, so it’s fresh in his mind. Alex borrows material like this a lot. But he doesn’t follow his mom’s advice. Alex never stops.” —Josh McCoy, climbing partner

“When I’m soloing, I’m not thinking about anything. I’m physically executing a plan. It’s like asking a gymnast what they’re thinking about while they’re doing a routine.”

“Obviously, Alex can do this really well. But he doesn’t understand why others can’t.” —Tommy Caldwell, climbing partner

“There’s a quote that I like: ‘Being a professional means doing the things you love to do on the days you don’t feel like doing them.’ Sometimes you train even though you’re not motivated, because you’re like, Well, I’ll be better if I actually put in the hours.”

“Alex has a deep innate drive. He feels the need to keep achieving in climbing, or he faces depression.” —McCoy

“I’m pretty particular about always putting things in the same pockets, or the same pouches in backpacks. Everything goes in its place. My luggage is always packed the same way, and I always wear the same clothes for travel. You’ve got to keep things orderly so your ship is sailing smoothly.”

“You should see him with my phone. He constantly wants to adjust my updates, erase old voice mail, delete extra alarms. It’s like he’s in a neurotic-tendencies candy shop.” —Sanni McCandless, girlfriend

“I don’t like running, and I almost never run. But I was in Telluride, Colorado, this summer when a friend texted me to say that Robert Redford wanted to meet me and I had 20 minutes to get there. I was like, Holy shit! So I sprinted a mile or so across town. As I was running I thought, this is why you always maintain some basic fitness. It was sort of the modern-day equivalent of being chased by a lion.”

“Alex is a bit of a celebrity dork. Have you seen all those selfies with Jared Leto?” —Wright

“It’s not about controlling your fear. It’s about broadening your comfort zone. You need to systematically expose yourself to something until it’s not scary.”

“After he did 60 Minutes, Alex had to learn to speak in public, which was ten times more terrifying for him than climbing without a rope. But he’s learned to be quite charming.” —Wright

Des Linden

American woman who broke through at Boston

�����Ի���’s historic win at the 2018 Boston Marathon continued a pattern of success for American women distance runners. As the numbers below suggest, an even more exciting future is very likely on the way. —Will Cockrell

Four American women among the favorites before this year’s marathon: Linden, Shalane Flanagan, Jordan Hasay, and Molly Huddle. “It would have been really heartbreaking if we didn’t win,” says Linden. “That was just about the best squad we could have put on the line.”

Seven American women who placed in the top eight finishers at Boston. “That depth has been building for a while,” says Linden. “From the 800-meters runners on up, we’re seeing a lot of success right now.”

Thirty-three years since the last American woman, Lisa Larsen Rainsberger, won Boston. “Lisa was thrilled,” says Linden.“She’d been hoping someone would do it soon.”

Fourty-six years that women have been allowed to compete in the Boston Marathon. (Eight entered and finished the 1972 race.) “You always think about history with Boston,” says Linden. “You feel like you’re running in those amazing women’s footsteps.”

Six seconds Linden waited for Flanagan to take a bathroom break roughly halfway through the Boston course. “I knew it was important to help her get back with the lead pack” says Linden. “The more Americans we had with us, the better our odds.”

Tommy Caldwell

That other guy on El Cap

When Alex Honnold decided to grab back the climbing speed record for the infamous Nose route on Yosemite’s El Capitan this summer, he figured the best way to guarantee success was to get his good friend Tommy Caldwell to join him. This despite the fact that Caldwell had never set a speed record. “When Tommy commits to do something, it happens,” explains Honnold.

Caldwell is among the best and most dedicated big-wall climbers in history. He spent seven years almost entirely focused on completing the first free ascent—using ropes and anchors for safety only—of El Capitan’s Dawn Wall, which he completed with Kevin Jorgeson in early 2015. Their effort earned a shout-out from President Obama and is the subject of the other big climbing film released this fall, The Dawn Wall, by Sender Films.

As Honnold sees it, perceptions of Caldwell have always been half right. “His reputation as a good guy and a pillar of the community is super well-founded,” he says. But the assumption that Caldwell is just another naturally talented athlete couldn’t be further from the truth. “He never had a gift and rested on it,” Honnold says. “Everything he’s done, he was willing to make it happen. I wish I had his work ethic.” —M.S.

Bianca Valenti

Barrier-busting big-wave surfer

Despite the fact that women have long been surfing the world’s biggest waves—Betty “Banzai” Depolito was charging Waimea Bay, the legendary break off Oahu’s North Shore, in the late seventies—they’ve been given few opportunities to compete in big-wave contests. The first women’s heat didn’t take place until 2010, at Oregon’s Nelscott Reef Big Wave Classic. Last fall, after years of struggling to get support from the male-dominated surf industry, Depolito created a women-only contest at Waimea called Queen of the Bay, though it was canceled when the waves never came.

To date, no woman has ever competed in an event at Maverick’s, the monster swell south of San Francisco, even though Sarah Gerhardt broke the gender barrier there back in 1999, just weeks before the first Maverick’s event. That’s about to change, following the persistence of and the , which she cofounded with three other pro women in 2016. That same year, the California Coastal Commission required the group behind the Maverick’s contest to include women in order to secure permitting. And CEWS then stepped in to ensure that the women’s purse matched the men’s.

“The organizers had told us, ‘Women aren’t ready’ or ‘It’s unsafe,’ or they’d say, ‘Yes, you can compete,’ but then nothing would happen,” Valenti says. “When we started using policy to try to make a change, things finally shifted.”

Six women, including Valenti and Gerhardt, were invited to compete in 2016. The event was canceled that winter (due to unrelated legal issues) and again earlier this year (due to lack of swell), but the weather window reopens this winter, and ten women are on the roster to be called if suitable waves arrive. Just as important, the contest is now part of the World Surf League, which Valenti is lobbying for a lot more changes.

“We still aren’t in every event, and we’re not getting pay equality,” Valenti says. “But this is a good first step.” —Megan Michelson

Naomi Osaka

Humble champion

Frequently overlooked in the controversy surrounding Serena Williams’s dispute with an umpire at the U.S. Open tennis final was the fact that when Osaka hoisted the trophy, she became the first Japanese player to win a Grand Slam event. It won’t be her last.

Kikkan Randall

Cancer-crushing Olympian

In May, three months after Randall teamed up with Jessie Diggins to capture the first ever Olympic medal, a gold, for women cross-country skiers, in Pyeongchang—Randall’s fifth Games and her first as a mother—the 35-year-old was diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer. She’s chosen to make her battle with the disease public and candid, sharing images and videos on social media and her blog in an effort to show people what the process is really like. “Strangely, this chemo experience is kind of like my athletic career,” Randall said in a video she posted in September. “I’ve got to get enough rest, I’ve got to eat right, I’ve got to hydrate—and I’ve got to not push myself too much.” —M.M.

���Ի����������������������

Skier who dropped K2

On July 22, Polish mountaineer Andrezj Bargiel became the first person to make a full ski descent of 28,251-foot K2, the second-highest peak on earth and one of the most dangerous. At least two of the handful of skiers who have attempted previous descents perished in the process. This year, the mountain’s notoriously wicked weather was milder than usual, boosting Bargiel’s odds. His drop took roughly eight hours, including one spent waiting out poor visibility at 26,000 feet. Bargiel, who had already skied down three of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks, was both elated and relieved when he finally made it to base camp. “To be honest, I’m glad that I won’t be coming here again,” he said. Drone video footage of his run went viral almost instantly, but few who saw it realized the long history behind the big moment. —W.C.

1970

Japanese climber Yuichiro Miura carves a few turns on Everest’s South Col. They are believed to be the first ski tracks made above 8,000 meters.

1982

Swiss extreme skier Sylvain Saudan makes it down Gasherbrum, likely completing the first full ski descent of an 8,000-meter mountain.

2000

Slovenian Davo Karnicar makes the first complete ski descent of Everest.

2001

Italian Hans Kammerlander starts skiing from K2’s summit, but after reportedly witnessing a climber fall to his death, he completes his descent in boots.

2009

Weather forces American Dave Watson to begin his planned K2 ski descent shy of the summit.

������������������Dz������

Centurion marathoner

World War II pilot-instructor Orville Rogers lived what many would consider an entire lifetime by age 50, when he discovered running. Now 100 years old, he continues to pound the pavement—and smash age-group records along the way. We asked him how we could follow his lead. —W.C.

“I only started running competitively about 11 years ago. I looked up the world records and I thought, Hey, maybe I can do that. And I did. I set new times in the 400 and 800 meters and slaughtered the mile record. I think I broke it by two minutes.”

“I follow all the scientific reports on exercise and longevity. I eat a good breakfast with lots of multicolored fruits. I like to get seven or eight hours of sleep a night, and I nap every afternoon, whether I want to or not. But I do eat a lean steak once a week, and I have an affinity for fried okra.”

“When I turned 100 at the end of last year, I entered five races and broke five records. There’s nobody in my age group anymore. If I’m still alive in five years, I’ll be in a new bracket!”

“I had to learn a lot on my own. My dad deserted my mother, my sister, and me when I was six. If I had taken a little bit of a different course in life, I could’ve gotten into drinking and drugs.”

“Exercise isn’t everything. I’ve had two bypass surgeries.”

“Above all else, I think my health and longevity have been because of my belief in God. It’s well established that believers live longer.”

“The records are great and all, but I run because I always feel better afterward.”