The number 10 story on this list has little to do with sports science. In 2012, Paul Ryan told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt that he ran a 2:50 or so marathon. He was off by about an hour. The moderator of an online running forum pitched a simple question to the masses looking to find proof of Ryan’s race time. That got the ball rolling in the mind of at least one journalist. When it comes to sports marketing and achievement, a healthy dose of skepticism is warranted. Claims from athletes about doping, claims from companies about their products, and even small claims from politicians about seemingly unimportant athletic achievements can now be questioned by anyone in a public way. This year, that questioning came from a scientist worried that overzealous marketing was causing unnecessary deaths during sporting events, a non-profit non-governmental agency carrying on the investigation of an athlete that was dropped by the federal government, and a woman who started a class action lawsuit against a growing shoe company. They all had one thing in common: a quest for the truth.

10. Paul Ryan’s Marathon Snafu

09. Ted Ligety and Lindsey Vonn Battle the FIS

08. Caster Semenya’s Race

07. A Ski Season Burned at Both Ends

06. A Bible on Overhydration

05. A Barefoot Suit

04. Micah True’s Death and the Too Much Running Debate

03. Sarah Burke’s Death

02. Oscar Pistorius Has His Olympic Moment

01. Lance Armstrong’s Fall

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Paul Ryan’s Marathon Snafu

The Republican vice presidential nominee shaves more than an hour off his race time in an interview

Read and Watch More

1.

2.

On August 22, Republican vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan told conservative radio host that he ran a marathon, “under three, high twos. I had a 2 hour and 50-something.” Hewitt expressed amazement. Ryan said, “I was fast when I was younger, yeah.”

On a LetsRun.com , Bill Walker started a discussion about Ryan: “Does anyone know the marathon and the year?”

Scott Douglas, a journalist for Runner’s World, started . He found out that Ryan had run the 1990 Grandma’s Marathon in Duluth, Minnesota, with a time of 4 hours and 1 minute. That is a pace of more than nine minutes a mile, instead of say, a pace of less than seven minutes a mile. The story ended up plastered on the front page of a number of websites and Ryan admitted his error. “If I were to do any rounding, it would certainly be to four hours, not three,” said Ryan.

Nick Thompson of the New Yorker whether Ryan lied about his time or simply made a mistake. More stories began appearing calling the politician’s statements into question. Did Paul Ryan really have body fat? Did Paul Ryan 40 of Colorado’s 14ers? How did Paul Ryan lie?

Psychological studies have shown that people tend to lie to satisfy their own self-interests. That seems obvious. A new study published this year in showed that people playing a dice game and offered a reward for good results were more likely to lie about their rolls when presented with less time to report. Ryan was doing an interview, but he certainly wasn’t under tight time restrictions or high pressure to respond to questions on a conservative radio show. Why would anyone running for public office lie about a sporting event in which records are kept, especially in an age when everything is scrutinized relentlessly online? I don’t have a good answer for that.

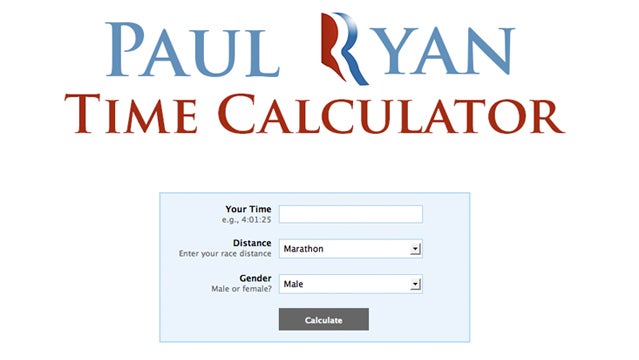

During the speculation and commentary, an was created, just in case anyone wanted to answer the most creative question posed in response to the politician’s snafu. How fast would you exaggerate your marathon time using Paul Ryan’s math?

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Ted Ligety and Lindsey Vonn Battle the FIS

American skiers take on skiing’s ruling body over rules about ski length and gender restrictions

Read and Watch More

In July 2011, the International Ski Federation decided to require longer, straighter skis to improve safety, beginning with the 2012-2013 season. They wanted to reduce risk after finding out that from 2006 to 2010 nearly a third of skiers suffered an injury. They teamed up with the University of Salzburg and interviewed 63 experts before coming out with the decision to increase ski length. The change wasn’t a result of peer-reviewed studies, but rather a set of recommendations from ski experts. The skis required for giant slalom, one of three alpine disciplines, had the biggest change. One of the athletes in that discipline, American skier Ted Ligety, complained the loudest. “It would be like going from a sports car to driving a semi truck,” Ligety told ���ܳٲ������’s Mike Webster in 2011. “It’s just such a huge difference.

Ligety that the FIS was a tyranny and said the change would tip the scales in favor of larger skiers. He also that the change would reduce injuries. He . In late December 2011, David Dodge, the former chief research and development engineer at Rossignol USA, the scientific basis for the switch and said that the new rules might lead to unstable leg geometry and a higher probability of ACL injury.

Queue the 2012 season. Ligety on the longer skis, in one race by more than two seconds. Other athletes wanted Ligety’s skis checked. The FIS assured them the American’s gear met standards. As for the injuries? The FIS has not responded to a request for injury numbers so far this year.

has been skiing on men’s planks for . She has also with men. Last winter, Vonn captured her fourth overall World Cup women’s title in five years. This winter, she decided to take what she said was the next logical jump to raise the stakes, requesting that the FIS let her race against the men at Lake Louise. The FIS refused her request. “The Council respected Lindsey Vonn’s proposal to participate in men’s World Cup races and confirmed that one gender is not entitled to participate in races of the other and exceptions will not be made to the FIS Rules,” they said in a written statement. “In terms of her request to participate in the men’s downhill in Lake Louise, she is welcome to submit a request to the Organising Committee and jury to be a forerunner.”

In other words, Vonn could ski the course before the men, but could not compete against them directly. In December, the 28-year-old said she wasn’t satisfied, and hinted she might try a different approach to achieve her goal. “So right now I’m looking into options,” she told . “My father is an attorney, so I’m just seeing if there’s any options, legally, that I can take.”

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Caster Semenya’s Race

How should officials and the media handle questions about sex in sports?

Read and Watch More

1.

Before South African runner Caster Semenya ran the 800m women’s final in the 2012 London Olympics, David Epstein of Sports Illustrated that she would face judgment whether she won or lost. “If Semenya wins the gold, she is likely to be accused of having an unfair advantage,” wrote Epstein. “If she runs poorly, she is likely to be accused of sandbagging the race so as not to be accused of having an unfair advantage.”

He was right. Semenya took silver, and explained that she didn’t win because of a tactical error—going too late into her kick. Questions online as to whether she threw the race. No definite answers were to be had.

Semenya burst onto the scene as a running phenom in 2009. Her strong finishes combined with a strong jawline, defined torso, and deep voice led many to question her sex, sometimes cruelly. Those questions played out publicly as she was subjected to a variety of private tests. She was from a small town in South Africa, but her condition gained worldwide attention, and news organizations followed her story closely. On September 11, 2009, a in Australia’s Daily Telegraph said that she had no womb or ovaries and did have internal testis, but those results were not confirmed by the organization that ordered the tests or Semenya. The results, if true, would mean that Semenya is intersex—a category for people whose physical development and sexual organs differ from the accepted understanding of male or female. There is no ultimate determination, in sport or in life.

The handling of Semenya’s case by officials and the media was unfortunate, and, at times, probably inexcusable. She was still a teenager and many of those people in charge of her may have not had her best interests in mind. Private details went public as officials were trying to figure out how to handle the situation and she was dealing with the news. Ariel Levy of the New Yorker detailed all of this beautifully in a November 2009 profile of Semenya. Anyone who wants to comment or express a public opinion about Semenya’s sex and race results would be wise to read that story first.

As for Semenya, she moved on from questions about her finish by saying she would concentrate on Rio. “I see a pretty good future for me,” she . “The most important thing is to train, I just have to focus on my career and forget about the past.”

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: A Ski Season Burned at Both Ends

A massive report puts an economic estimate on the effects of climate change on snow sports

Read and Watch More

1.

2.

Last winter was the fourth warmest since records were first kept in 1896 and the third lowest for snow cover extent since that was first measured using satellites in 1966. As a result of the lack of snow, half of the nation’s ski areas opened late and almost half of them closed early. The news going forward doesn’t get better, at least according to a put together by Protect Our Winters and the Natural Resources Defense Council. They predict that warmer winters, reduced snowfall, and shorter snow seasons will spell economic disaster for the winter sports industry. To demonstrate how climate change might affect the snow sports industry moving forward, their report showed how lower snowfall years and rising average temperatures have affected the $12.2 billion U.S. winter tourism industry.

They listed four key economic findings:

1. “The downhill ski resort industry is estimated to have lost $1.07 billion in aggregated revenue between low and high snow fall years over the last decade (November 1999 – April 2010).”

2. “The resulting employment impact is a loss of between 13,000 to 27,000 jobs (6 to 13 percent employment change), with the 6 percent jobs difference corresponding to over 15 million fewer skier visits.”

3. “The largest changes in the estimated number of skier visits between high and low snowfall years (over one million) occurred in: Colorado (-7.7 percent), Washington (-28 percent), Wisconsin (-36 percent), California (-4.7 percent), Utah (-14 percent), and Oregon (-31 percent). The resulting difference in economic value added to the state economy ranged from -$117 million to -$38 million.”

4. “In the Eastern region of the U.S. the states with the largest estimated changes in skier visits between low and high snowfall years were: Vermont (-9.5 percent), Pennsylvania (-12 percent), New Hampshire (-17 percent), and New York (-10 percent). The resulting difference in economic value added to the state economy ranged from -$51 million to -$40 million.”

Over the past decade, the ski industry has responded to changes in temperature and snowfall with technologies to improve artificial snowmaking. That adaptation may not last as the climate continues to warm, according to the report. Protect Our Winters and the Natural Resources Defense Council that ski resorts should more than ponder that reality. “Hopefully it will change the dialogue,” Chris Steinkamp, founder and executive director of Protect Our Winters, told ���ϳԹ���’s Mary Catherine O’Connor in December. “The National Ski Area Association has done great work at the resort level, but they’re not doing any lobbying for the climate.”

A Bible on Overhydration

South African sports scientist Tim Noakes says the scientific guidelines behind hydration are a sham

Read and Watch More

On May 1, 2012, Dr. Tim Noakes released a 429-page doorstop of a book summarizing three decades of study on overhydration in sports. He had already published more than 50 papers on the subject, but wanted to document everything he’d learned in one place for a very simple reason. “The science of hydration is utterly bogus,” he said in a 2012 TEDx Talk. “There is no science to it. It was dreamed up by marketers to sell product.”

Noakes began looking into the issue of overhydration in 1981. A man had just pulled his wife out of South Africa’s Comrades marathon because she didn’t recognize him. She eventually went into a coma. The woman had fluid in her lungs, a low sodium concentration in her blood, and swelling in her brain. Noakes didn’t know it at the time, but she had the first case he had seen of exercise-associated hyponatremic encephalopathy. That’s a clunky way to say she drank way too much water while exercising.

Over the next three decades, Noakes would pile up more evidence on the condition. Since 1981, he’s documented roughly 1,600 cases, 12 of them deaths, from hyponatremia in the medical literature. In the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, the conventional wisdom was to drink more during exercise. Noakes had promoted such an agenda himself at one time. But by the late ’80s, Noakes had evidence that said otherwise. Even in the mid-’90s, the American College of Sports Medicine said to drink as much as 40 ounces per hour. Noakes raised a red flag. In the past decade, they have changed their guidelines. The American College of Sports Medicine’s 2007 guidelines do not recommend drinking as much, but Noakes still isn’t entirely in agreement with the new rules. “Drink to thirst regardless of how much weight you lose,” he told ���ϳԹ��� in a June 2012 interview. “The ACSM guideline that one should not lose more than two percent body weight is contrary to the published evidence and the findings in elite athletes that drinking ‘ahead of thirst’ impairs exercise performance.”

Noakes does not make this list for his book alone. On September 13, South Africa’s National Research Foundation awarded him their Lifetime Achievement Award. He has committed himself to questioning conventional wisdom about nutrition and fitness by conducting longterm studies that rely on huge amounts of evidence. He tackles big questions. Do muscles regulate exercise performance or is it something else? Is it possible to swim in Arctic or Antarctic waters for a long period of time without dying? Are low fat diet diets really healthy for you? He says he’ll be studying that last question for probably the next two decades. “What I’ve learned in life is that 50 percent of what we learn is wrong,” he said in the 2012 TEDx Talk. “The problem is we don’t know which 50 percent it is, and our job as educated people is to find out which 50 percent is which.”

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: A Barefoot Suit

A woman files a class action lawsuit against Vibram

Read and Watch More

1.

2. The Vibram lawsuit

3.

On March 21, a woman filed a class action lawsuit against Vibram for deceptive advertising regarding the company’s FiveFingers line of barefoot running shoes, saying the companies claims about health benefits were not supported by well-designed scientific studies. Peter Vigneron wrote a thoughtful post for ���ϳԹ��� about the lawsuit when it was first filed, and you should read it. “Unfortunately, the non-theoretical evidence that running barefoot, or running with ‘good form,’ confers unique benefits over regular shoes is mixed and incomplete,” he said. “No controlled studies have tackled that question and found in favor of barefoot running.”

The lawsuit is , and not without precedent. On September 28, 2011, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reached a settlement with Reebok in which the company agreed to pay $25 million in customer refunds for deceptive claims that their EasyTone and RunTone shoes would provide more tone and strength to leg and buttocks muscles than regular shoes. Reebok’s claims were a bit more specific than what Vibram has stated. For example, Reebok claimed that walking in EasyTone footwear had been proven to lead to 28 percent more strength and tone in the buttock muscles, 11 percent more strength and tone in the hamstring muscles, and 11 percent more strength and tone in the calf muscles than regular walking shoes. They didn’t back that up.

Upon announcing the decision against Reebok, the FTC issued a strong statement to companies. “The FTC wants national advertisers to understand that they must exercise some responsibility and ensure that their claims for fitness gear are supported by sound science,” David Vladeck, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection.

How much did that statement change things? In July 2012, Nicholas Bakalar in The New York Times about a study published in BMJ Open in which authors looked at claims made in health and fitness advertisements in magazines and on websites. Of the dozens of fitness products whose claims they examined, not one was supported by scientific research. Geez, whatever happened to the days when companies who didn’t have scientific evidence built their advertising around inspiring general statements and big personalities? Oh, . And . And….

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Micah True’s Death and the Too Much Running Debate

New studies question whether prolonged exercise over a long period of time is bad for your heart

Read and Watch More

1. Running scared

2.

3.

On Tuesday, March 27, ultrarunner Micah True set off for a 12-mile run through New Mexico’s Gila National Forest and didn’t return. Four days later, a search party of his friends found him dead, bruised, and lying on his back with his legs in a stream. Roughly five weeks later, on May 7, the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator that said True died of idiopathic cardiomyopathy—heart disease with an unknown cause.

More , True had dilated cardiomyopathy. The wall of his heart was enlarged and stretched thin, which would have made it increasingly ineffective at pumping blood throughout his body. As Tom Meersman explained in a for Runner’s World: “What autopsy reports can’t tell us definitively is what killed True. It’s reasonable to imagine a situation in which a runner with dilated cardiomyopathy and mild dehydration, who is out on a run, has their cardiac output decrease to the point of medical emergency. Was this the (im)perfect storm that killed Caballo Blanco? We will never know for sure.”

Still, at least one cardiologist suggested that the cause of True’s death could have been the result of chronic excessive endurance exercise, according to a recent ���ϳԹ��� article by Erin Beresini. That cardiologist was James O’Keefe, the director of the Preventive Cardiology Fellowship Program at Missouri’s Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute. He and fellow cardiologist Chip Lavie have published several exercise reports in the past two years suggesting that people who run for longer distances for prolonged periods of time have more adverse health effects and a higher mortality than those who run for shorter periods of time. The scientists have also said that extreme runners have fewer adverse health effects and a lower mortality than the population as a whole. As Beresini reports, what those scientists have suggested is still being called into question by their peers.

Amby Burfoot of Runner’s World conducted with both cardiologists about what they’ve found. The takeaway from that interview came from O’Keefe, who said: “The latest data from our studies and others strongly suggests that the ideal dose of daily vigorous exercise is about 30 to 60 minutes. Heck, you can get the majority of improvements in cardiovascular risk and longevity with a mere 20 to 30 minutes of walking per day. If you do more than 60 minutes of strenuous exercise daily, you start to lose some of the health benefits seen with lesser amounts of physical activity.”

That’s not to say what the scientists have shown is definite. In , Alex Hutchinson, who writes Runner’s World‘s Sweat Science blog, to issues with the scientists’ methods. Burfoot summed up his thoughts on the studies and what they show quite effectively in a separate . “Many aspects of exercise and running also follow a U-curve,” he wrote. “This is why many people believe the moderate approach is the smartest path to follow. Of course, you’ll never qualify for the Boston Marathon that way. We all have to make our choices.”

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Sarah Burke’s Death

In the immediate aftermath of the skier’s fatal injury, questions are raised online about helmet, risk, and health insurance

Read and Watch More

1. Parting shot: Sarah Burke

2. Will Obamacare mean relief for uninsured athletes?

On January 19, 29-year-old freestyle skier Sarah Burke died after hitting her head and tearing her vertebral artery while training in a Park City, Utah, superpipe. Burke’s legacy will be many inspiring things to many people, including that her lobbying was one of the women’s halfpipe skiing was added to the lineup for the 2014 Olympics.

Burke’s injury occurred on January 10 in an age of rapidfire online news and commentary. Almost immediately, two conversations arose. The revolved around head injuries in skiing and pushing the limits. People wanted to know whether Burke was wearing a helmet and how much she was pushing herself beyond her abilities. As ���ϳԹ���’s Grayson Schaffer reported, Burke was skiing her normal routine, suffered what some sites reported as an unremarkable fall, and was wearing a helmet.

That Burke was wearing a helmet was not a surprise, and indicative of a trend in skiing and snowboarding in the United States. Helmet usage has gone up from 25 percent of riders in 2002/2003 to 57 percent in 2009 /2010 to 67 percent last winter. A November study published in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Surgery Care said that wearing helmets clearly reduced the risk of head injuries during skiing and snowboarding and did not increase the risk of neck injury, cervical spine injury, or risk compensation behavior. Roughly 10 million Americans ski or snowboard in the United States every year, with 600,000 injuries reported annually and up to 20 percent of those occurring to the head. Twenty-two percent of those injuries lead to loss of consciousness, concussion, or worse, which is why many parks now require helmets in pipe activities—but there is no across-the-board requirement that skiers or snowboarders wear helmets at resorts. The study’s authors making them mandatory. And the lead author, of Johns Hopkins University School, wearing helmets could help reduce hospitalization, death, and prevent an increase in health care spending.

The second conversation began after Burke’s agent, Michael Spencer, started a fundraising page online to help Burke’s family pay roughly $200,000 in . Her fans came through, giving more than $270,000 in less than a week. People wanted to know why Burke’s treatment wasn’t covered by health insurance. Gordy Megroz reported the answer in his November story, “Will Obamacare Mean Relief for Uninsured ���ϳԹ��� Athletes?” Burke was training for an unsanctioned event in the United States, where her Canadian Health insurance and the Canada Freestyle Ski Association’s plan did not cover her. One fan asked Monster Energy why the company didn’t foot the bill. Athletes chimed in on the difficulty they faced in obtaining insurance. “Securing reliable insurance is the hardest part of our job,” tweeted skier Cody Townsend.

When changes to the nation’s healthcare plan go into effect, it won’t make getting health insurance easier or more affordable for adventure athletes. To help those looking, some athletes have . Sports clubs have offered up health and life insurance packages, as the does for its members. Other services, like , help individuals find specific coverage. If you know of any other resources for health insurance, feel free to share them in the comments section below.

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Oscar Pistorius Has His Olympic Moment

South African sprinter becomes the first double amputee to run in the Olympics

Read and Watch More

The raw athletic performances of the 2012 Olympics are easy to list. Jamaican Usain Bolt dominated the 100m and 200m for the second Olympics in a row, easily reclaiming the crown of world’s fastest man. Manteo Mitchell running his leg of the 4×400 with a broken femur, helping the United States relay team to gold. Swimmer Michael Phelps touched the wall six times to win medals, four of them gold, as he racked up the most medals for any one Olympian in history, with 22.

South African sprinter Oscar Pistorius only had to line up to . No other Olympian had to fight a longer, more contentious legal and scientific battle just to compete. In order to step onto the track for the 400-meter sprint in London, the double amputee had to wage a marathon of a public fight.

The science behind his battle has been well documented—at issue was whether carbon fibers blades gave Pistorius a competitive advantage. In 2007, the International Association of Athletics Federations banned him from competition after Peter Brüggemann, a professor of biomechanics at the German Sports University in Cologne, said Pistorius’ blades allowed him to use 25 percent less energy than able-bodied athletes. Pistorius appealed the decision with the Court for the Arbitration of Sport. A group of six scientists including conducted more tests.* Two testified to the CAS that Pistorius’ performance fell within the range of an able-bodied athlete. The arbitration panel overturned the IAAF decision and the door opened for Pistorius to compete in the Olympics—if he could qualify. Two scientists from the group later declared that Pistorius had an advantage, but it didn’t change anything. Pistorius qualified.

The debate didn’t stop, nor will it. The debate actually picked up after the Olympics, when Pistorius competed in the Paralympics. In the 200m finals, Brazilian Alan Oliveira flew by the South African in the straightaway to take the gold. Pistorius cried foul, saying the length of his competitor’s blades gave him an unfair advantage. He later apologized, but the comment relit the debate over prosthetics. All of that is getting ahead of the moment.

On August 4, before the preliminary heat in the men’s 400m, the crowd roared for Pistorius. He quietly put his carbon fiber blades into the starting blocks, and people waited for the gun, prepared to watch a man without both of his legs do something he had fought for years to be able—never mind allowed—to do: run against the world’s best athletes on the world’s biggest stage.

*This article originally state that nine scientists conducted tests. That was wrong. It has been changed to say that six scientists conducted tests.

The Top Sports Science Stories of 2012: Lance Armstrong’s Fall

USADA charges the cyclist with doping

Read and Watch More

Lance Armstrong didn’t just dope, he was the ringleader of the grandest doping scheme in the recent history of team sports. That’s what the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) said in October when they released a roughly 200-page report that detailed the violations committed by Armstrong as he pedaled his way to seven Tour de France victories after fighting off cancer. The report painted Armstrong as a bully. The cyclist didn’t respond. He kept a promise he made in an August 23 statement in which he said he would not fight doping charges brought against him by USADA. He kept quiet.

In late October, the International Cycling Union agreed with USADA’s findings and officially stripped Armstrong of all his victories from August 1, 1998 forward—including seven Tour de France wins—and banned him from the sport. All of Armstrong’s sponsors dropped him. He resigned as the chairman and of Livestrong, a foundation he built to help others in their fight against cancer.

Armstrong certainly wasn’t alone in his doping. The USADA report said that 20 of the 21 podium finishers in the Tour de France during the seven years that Armstrong won had been directly tied to likely doping through admissions, sanctions, public investigations, or by exceeding the UCI hematocrit threshold. The report showed what the book by Tyler Hamilton and Daniel Coyle already had: that the science of doping was more advanced than the testing used to catch dopers, and when it wasn’t, the athletes used childish tricks and a culture of silence to avoid getting caught. The thing is, , many of the other riders took to the and for lying and cheating. Armstrong didn’t fight the charges, didn’t take to the press, and didn’t apologize. Through the end of the year, he remained quiet, only posting the random tweet. One of those tweets included a photo of him resting on his back on a dark couch in a room with his framed yellow jerseys in the background—a strange and quiet position for someone who had charged so hard, so long, so publicly.