The big thing in sports nutrition in the 1990s was the “window of opportunity.” Down some carbs immediately after a workout, , and you’ll replenish your fuel stores 75 percent more quickly than if you down the same carbs two hours later. There’s certainly some truth to that, but has shown that the differences in refueling equal out within about eight hours. Slavish devotion to refueling during the magic window, it turns out, really only matters if you’re training hard twice (or more) per day.

But new research offers a fresh perspective on the question of nutrient timing for athletes. A pair of studies by researchers in Denmark and Norway dig into the concept of “within-day energy deficiency” and its implications for endurance athletes. The idea is that even if you’re getting enough calories to meet your needs each day, you might still be suffering some negative health effects if you spend too many hours in a caloric deficit.

The most recent study, in the International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, followed 31 male cyclists, triathletes, and runners. Their resting metabolic rate was measured and then compared to their predicted metabolic rate based on their body size and composition. Those whose measured rate was more than 10 percent lower than the predicted rate were classified as having a “suppressed metabolic rate,” a likely indicator that their bodies are not getting enough calories to support their training plus essential bodily functions. Of the 31 subjects, 20 had suppressed metabolic rates.

To understand what factors might contribute to this problem, the researchers tracked calorie intake and expenditure on an hour-by-hour basis for four consecutive days. The key point: There were no overall differences in calorie balance between those with normal and suppressed metabolisms—so the problem wasn’t necessarily that those with suppressed metabolisms weren’t eating enough.

Instead, the differences showed up in the hourly breakdown. The athletes with suppressed metabolism tended to spend more hours each day in significant caloric deficit (more than 400 calories) and had larger peak caloric deficits. The problem, in other words, was when they chose to eat.

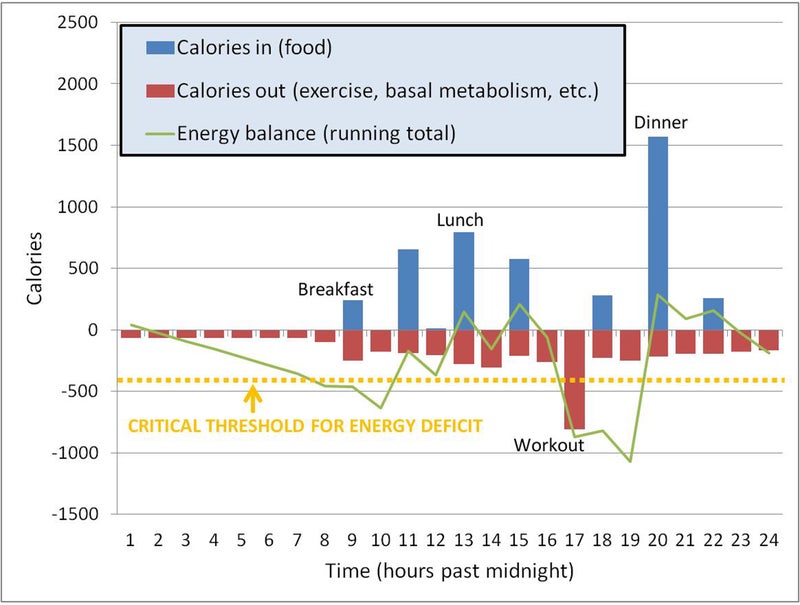

Here’s a graph based on sample data from the paper, showing a typical pattern. The red bars show calories burned from factors like resting metabolism, exercise, digestion, and so on. The blue bars show calories consumed. The green line shows the cumulative balance between those two factors:

During the night, the athlete drifts into mild energy deficit. This isn’t a problem initially. But he doesn’t take in many calories early in the day, and as he gets up and starts moving around, he drifts over the dotted line into a zone where his body is having to prioritize where to use limited fuel. And when he works out at 5 p.m., he pushes himself deep into a deficit that he doesn’t dig out of until a massive dinner at 8 p.m.

Does this matter? In the study, there was a significant correlation between the largest single-hour calorie deficits and hormonal disturbances like lower testosterone and higher cortisol. This is a problem, because it may hinder your ability to recover from workouts and avoid overtraining. In a similar study of female endurance athletes by some of the same researchers, hourly energy deficits were also associated with hormonal disturbances (lower estradiol, higher cortisol) and menstrual dysfunction, even when total calorie balance was similar.

One obvious solution is to go back to the “window” concept and focus on cramming in calories immediately after workouts. That would address some of the issues in the graph above, and these findings certainly add weight to the idea that it’s important to get calories on board reasonably soon after a long or hard workout.

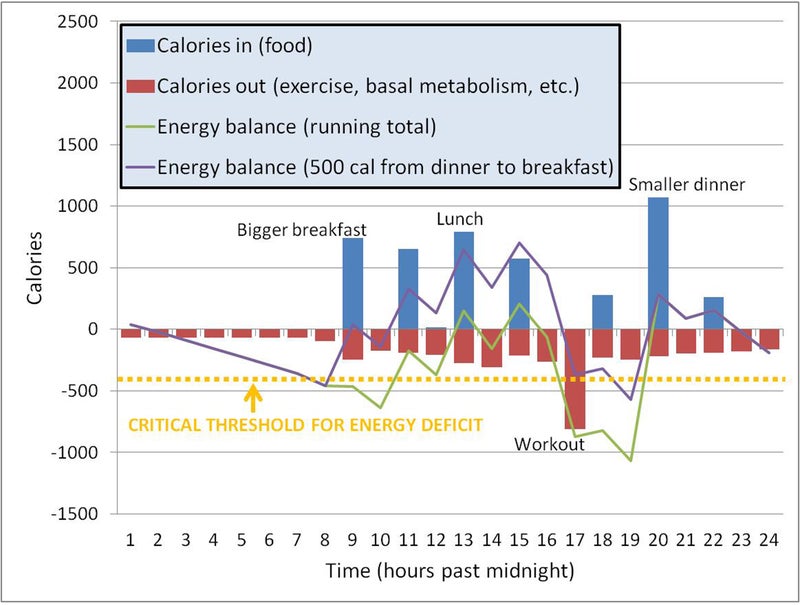

But focusing only on post-workout nutrition is too narrow a view, I think. Look at the overall pattern of calorie intake during the day: It’s heavily skewed toward dinner, when the day’s calorie burning is all done. I’ve replotted the same data with one small change: moving 500 calories from dinner to breakfast. Dinner is still the largest meal of the day and breakfast is still the smallest, but it’s not quite as skewed. And look at how the energy-balance curve changes as a result:

As it happens, that’s very similar to . Your ability to repair and build muscle depends on protein, and the more you get, the better—but only up to a point. Most of us get plenty of protein each day, but we tend to stack it at dinner (a typical North American pattern is 10 to 15 grams at breakfast and lunch, then 90 grams at dinner). As a result, you end up with less-than-optimal muscle synthesis earlier in the day and more protein than you can use in the evening.

The general message, then—both for protein and for calories in general—is to distribute your food intake throughout the day, paying particular attention to the time around workouts where you’re burning a lot of calories. It’s not that you should never incur a caloric deficit; in fact, draining your muscles’ fuel stores may well be one of the signals that tell your body to adapt and get fitter. Just think of your body as a rental car: It’s fine to empty the tank, but if you leave it empty, it’ll cost you much more in the long term.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available! For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .