Ed Burke’s Got a Rocket in His Pita Pocket

Sick of protein shakes and energy biscuits? Meet the exercise physiologist who has revolutionized sports nutrition with a radical new diet for athletes—real food.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

I am slumped against the counter in Ed Burke's kitchen, just back from a 30-mile bike ride, reeling from low blood sugar and watching with a mix of horror and shattered expectations as the 51-year-old nutrition expert loads his plate with a fried chicken burger on a plain white bun.

Edmund R. Burke, you must understand, is a fitness guru and dietary Jedi Master who has helped bicycle racers at all levels maximize their athletic potential. Just days ago, I began my pilgrimage at his octagonal house in Colorado Springs, my own personal Mecca, hungry for athletic rapture, for the guidance that would transform me from a 39-year-old cyclist who has never won a race into a middle-aged Lance Armstrong. I'd read Burke's many books and columns on bike racing and training and nutrition, marveled at his work with American cycling heroes like Armstrong, Greg LeMond, Marty Nothstein, and Rebecca Twigg. I'd even used the products he has helped develop or written about, like the CamelBak and the Polar Heart Rate Monitor. Most recently, however, I'd become obsessed with Burke's latest innovation, a four-step nutritional approach to recovering from strenuous training or competition that is not only changing the way endurance athletes eat but is igniting the next big performance breakthrough.

In fact, ever since I read Burke's 1999 book , my tendency toward training by the numbers has blossomed into a full-scale mania. My pantry now bulges with canisters of predigested whey powder and glucose polymers, with antioxidants and creatine and glutamine and extract of grape seed. My racing bike has become a rolling display case of performance gels and drinks and bars. And after even the easiest of training rides, I won't shower until I've consumed the correct amounts of carbohydrates and protein that, according to Burke, will replenish my fuel stores, repair my damaged muscles, and let me train harder all over again the next day.

And yet, after spending the last few days with Burke, I'm having doubts about my nutritional messiah. In a deli at the University of Colorado's Colorado Springs campus, where Burke is director of the exercise physiology program, I caught the slender athlete-turned-researcher dousing his coffee with a small waterfall of half-and-half. I saw him ogle a plate of chocolate éclairs and then joke that such foods weren't fatal. As if. And now, at a time when Dr. Recovery ought to be drinking something technical and precise, like a whey shake or one of the dozens of premixed “recovery” products spawned by his very own work, Burke sits down to a meal straight out of a junk-food fantasy: a leftover chicken burger. Not only does he seem to lack the kind of rigid self-discipline I've always associated with a high-performance diet, but the man eats everyday food, without measuring portions, without counting calories, and without a side dish of pharmaceutical supplements.

Burke meets my incredulous stare. “Hey, it's got carbs and protein,” he says, shrugging his skinny shoulders. Then he offers the first lesson in my long journey toward nutritional excellence. “Recovery,” he says, “has nothing to do with being a Food Nazi.”

In the loud world of sports nutrition, with its multimillion-dollar endorsement deals and outrageous claims of performance enhancement, Burke and his laid-back dietary pragmatism would be easy to miss altogether. Yet over the last decade, his work on muscle recovery-that is, on the foods and fluids your body needs after hard exercise-has emerged as the revelatory missing link in sports nutrition. Although eating before and during extended exercise has long been conventional wisdom, Burke was among the first to package and popularize the idea that what you consume after a workout-specifically during the 30- to 60-minute “glycogen window” when muscles are most greedy for infusions of energy from food-can replenish the fuel you've burned up, repair the microtears in your muscle tissue, and flush out the stress hormones that break down muscle protein during exercise. Recovery, we have come to understand, is when your muscles and cardiovascular system evolve, compensating for exercise's extra demands. And without proper recovery, there can be no athletic progress. Indeed, recovery nutrition has proven so effective that Burke's band of disciples now includes fat-tire legend Gary Fisher, six-time Ironman winner Dave Scott, nine-time New York Marathon champ Grete Waitz, many U.S. Olympic swimmers, and the entire Colorado Avalanche hockey team. “The old theory was that recovery was just something that happened after you trained hard, and there was really nothing you could do to speed up the process,” says former Olympic cyclist Chris Carmichael, Lance Armstrong's coach. “Burke changed all that.”

Happily, Burke isn't just interested in ministering to the pros. For although he knows precisely what nutrients professional athletes need to come back stronger the next day, Burke has a broader mission. Simply put, he believes that anyone who exercises-amateur triathletes, mountain bikers, snowboarders, rock rats, hell, even a cubicle-bound desk jockey who staggers his way up Mount Hood once every couple of years-can benefit, substantially, from a course in recovery nutrition. “You'd be amazed,” says Burke, “how many people finish their workout, head back to the office, have some Doritos and a Coke, then wonder why they feel so burned-out.”

It's enough to make a scientist weep-and to do everything he can to spread his nutrition gospel to the unconverted. Accordingly, Burke's liturgy is presented like an athlete's user manual in Optimal Muscle Recovery, dividing recovery into four easy- to-grasp steps that Burke has branded as R4 (restoring fluids, replenishing fuel, reducing muscle stress, and rebuilding muscle protein). And just to make sure we don't screw it up, he's gone a step further by helping design a prepackaged drink mix-Endurox R4, made by a company called PacificHealth Laboratories Inc.-based on his recovery program.

No surprise, the modest success of Endurox R4 has sparked a stampede of imitators for whom “recovery” is a million-dollar mantra. Everyone's got-or soon will launch-a recovery product, from boutique offerings like Hammer Nutrition's Hammer Pro (with 100 percent glutamine enhanced whey protein) and Smartfuel's Biofix (“the ultimate recovery drink”) to the big boys' products like Champion Nutrition's Revenge Pro and Gatorade's forthcoming Energy Drink. And while most companies make their own claims about their products, hoping to distinguish themselves from the competition, many have not only glommed on to Burke's basic premise, but are intent on committing the marketing dollars to launch a full-scale recovery-nutrition movement. Alas, in yet another variation on a classic business phenomenon, the mild-mannered doctor is now, like a bonking cyclist ahead of the peloton, in danger of being overtaken and left behind by his idea.

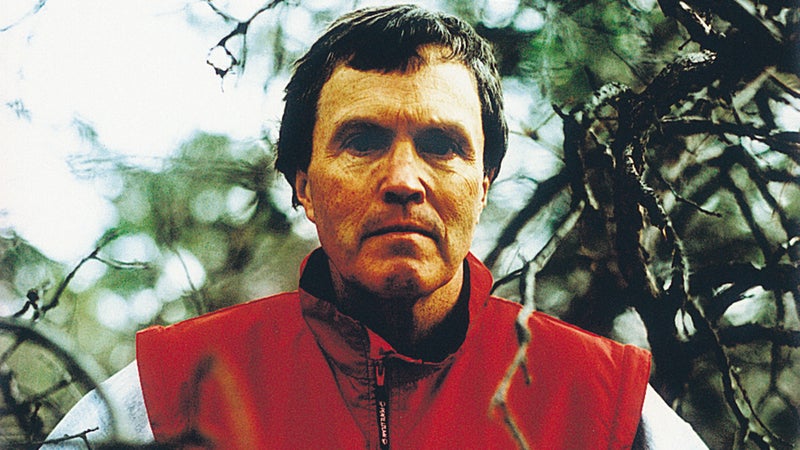

I met burke for the first time a few days earlier, in his cramped office on campus. He is the quintessential man in motion, a true hater of wasted time, and plunged immediately into my schedule for the next few days—a battery of physical tests, dietary analysis, and, finally, a crash course in recovery nutrition. As I jotted times and places, I tried to size up the man who would be showing me how to eat my way to athletic perfection. Eyeing Burke, I began to understand why he isn¹t exactly ready for prime time. Rangy and fit-looking, with gray-flecked brown hair and a squarish face, wearing plain glasses, a work shirt, and jeans, Burke comes across more like your high-school shop teacher than the Jack La Lanne of sports nutrition. He talks too fast, with a high-pitched voice and New York accent, and seems unable to sit still. And, somewhat surprisingly, he has almost no patience for the mechanics of self-promotion. When a magazine photographer and his assistant finally showed up lugging several hundred pounds of equipment, Burke seemed mildly annoyed by the modest amount of trouble even though their sole purpose was to make Burke look smart and savvy. “What kind of story is this, anyway?” he fussed. “Why don¹t you just snap some pictures and get on with it?”

If Burke is ill at ease as the next sports nutrition celeb, it¹s hardly surprising, given the backdoor way he¹s gotten here. He grew up in the Bronx, not as a curious boy chemist, but as a hell-raiser and C student whose main interest was football and whose vision of himself in the future, when he stopped to consider it, was as a PE teacher. In 1967 Burke enrolled at Ball State University, then an Indiana teachers' college, largely because he could play football there. But after a shoulder injury in his sophomore year, he hung up his pads and joined a fraternity that happened to field a team for a local marathon bike race modeled after Indiana University's classic, the Little 500. Burke signed up and soon found himself racing bikes seriously, eventually doing well enough to imagine a spot on the Olympic cycling team—at least until his coach sat him down for a chat. “I asked him what I should do next,” recalls Burke, citing his coach¹s quip about Burke¹s genetic shortcomings. “And he said, 'Take two weeks off, then quit.'”

But Burke, though not quite gifted enough to enter the ranks of the elite, wasn't through with sports. Returning to Ball State in 1973 to earn his master's degree in exercise physiology, he lucked into a class taught by Dave Costill, the veritable dean of American exercise physiologists. Costill, director of the school's Human Performance Lab, was not only turning Ball State into a breeding ground for sports scientists, but popularizing sports science itself by translating his research into books and magazines for lay readers and consulting with sports-drink companies (among them the makers of Gatorade, one of the first products designed to replace the carbohydrates and minerals lost in exercise). Enthralled, Burke switched his focus to exercise science with an emphasis on cycling, a sport that few other researchers were bothering with. That year Burke wrote his first column, on fluid replacement, for the now-defunct Bike World magazine.

In 1976, looking for a new challenge, Burke had an audacious idea: He would offer his services to the national cycling team. To his surprise, he was accepted, and accompanied the team to the Montreal Olympics. After that, Burke spent summers with the team, helping the coaches with VO2 max testing and turning research into practical advice for the athletes, including a young Chris Carmichael. “Ed knew his stuff, but it wasn't just in a theoretical way,” Carmichael recalls. “He always gave real advice and recommendations, as opposed to just some jumbled reference to research. Most sports scientists just quote the research, about what it indicates, etc., but they won't stick their necks out and say, 'This is how to use the information.' Ed would.”

Over the next decade, Burke leveraged his knowledge of exercise research, his racing experience, and his rapport with athletes into jobs that kept him at the center of his field. In 1980 he was promoted to staff physiologist for the U.S. Olympic Cycling Team, which included a young Greg LeMond. Anxious to learn the business of sports science, he also began developing his entrepreneurial side. He wrote his first book, a training manual called Inside the Cyclist. He helped develop a carbo-loading drink called Exceed while working on his Ph.D. (also at Ball State). He consulted with Polar, one of the first manufacturers of heart-rate monitors, and then wrote , which sold 29,000 copies—a best-seller in the modest canon of sports-training literature. He penned magazine articles about hydration and was hired as a consultant by the inventor of the CamelBak. (“This guy called me up,” says Burke, “told me he was riding around Texas with an IV bag full of water strapped to his back, and asked if I thought this could be a real product.”) It would not be until the 1990s, however, when Burke's star—in the guise of recovery nutrition—would begin to approach its zenith.

As recently as 1992, recovery was a small, unexciting topic having to do mainly with rest, massage, and stretching. Most athletes understood, at least vaguely, that exercise robbed them of fluids and fuel. But there was little consensus on a dietary response, and the available products were limited to either sugary cocktails or “protein shakes for muscleheads,” as Burke says.

Working with U.S. cycling team members who were complaining of overtraining and fatigue, Burke suspected that his weary athletes were suffering from something called chronic glycogen depletion. When you eat a starchy food like a banana or chug a sports drink, the carbohydrates get converted into blood sugar, or glucose, which muscles burn for energy. But any glucose not burned immediately gets stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen, which can be converted to energy later. Glycogen is, in fact, the body's preferred fuel during exercise. It's far easier to burn than fat and more readily available to the muscles than blood glucose. When you run out of glycogen during exercise, the body turns to blood glucose, which is almost impossible to maintain during training or competition. And you bonk. Worse, your body gets so desperate to maintain blood-glucose levels that it converts precious muscle protein into fuel as an emergency substitute. In short, glycogen is gold, especially to endurance athletes.

But glycogen replenishment is a tricky process. You can't start replacing it while exercising, because any carbs consumed are immediately burned by the muscles. Nor, more important, can you wait too long after exercise. According to research done in the 1980s by John Ivy, an exercise physiologist at the University of Texas (and another Ball State alum), athletes have a 60-minute post-exercise window in which muscles are primed to refuel. During this period, your muscles will convert carbs into glycogen up to three times faster than at other times. But miss it, and no matter how much pasta you eat later at dinner, more of the calories will end up as fat, or simply be eliminated as waste.

In the early 1990s, Ivy, who spent as much time in the lab as Burke did with athletes in the field, discovered that it was possible to open the window a little wider. Ordinarily, even super-receptive muscles convert only a small fraction of available carbohydrates into glycogen. Anything above a certain threshold—about 1.2 grams of carbs per kilogram of body weight—is effectively turned into fat. So Ivy tried a different approach. He knew the key to glycogen replenishment is the hormone insulin, which helps transfer glucose into the muscles and convert it into muscle glycogen. Aware that certain amino acids stimulate insulin production, Ivy added about a gram of amino-rich protein to every three to five grams of carbohydrates in his athletes' post-exercise meal. And lo! Glycogen synthesis jumped by 30 percent. In the realm of sports medicine, says Ivy, “it was a pretty big deal.”

The carb-protein combination was the final puzzle piece for Burke, who regularly crossed paths with Ivy at conferences and lectures. Now convinced that he had everything he needed to proselytize for the Next Big Thing in sports nutrition, he sat down to write a book showing athletes how to use hydration and glycogen replenishment to help solve the thorny problem of muscle recovery. Glycogen depletion wasn¹t exactly groundbreaking, but Burke, at his best when translating arcane research for the masses, realized that no one was applying the big picture to hardworking athletes. He knew from other research, for example, that exercise damages the immune system. He knew that exercise releases chemicals called free radicals, which damage muscles. He also knew that exercise produces hormones, like cortisol, that tear down muscle proteins, delaying muscle repair and contributing to muscle soreness. (This is why athletes take anabolic steroids, which counteract cortisol's effects and allow faster recovery.) Putting it together, Burke saw a bona fide syndrome: a cascade effect of fatigue, pain, and increased vulnerability to illness, all precipitated by improper recovery and all avoidable, or at least reducible, by a proper recovery diet. With Ivy's protein discovery, the science of muscle recovery now had the critical mass of research to go mainstream.

What Burke needed was a marketing conduit, which presented itself soon enough. Only a short way into work on his new book, Burke went to a trade show and met Robert Portman, president of Pacific Health, who was also looking into recovery as a way to exploit a rather huge gap in the sports-drink market. The industry, Portman told Burke, “is in a time warp.” The major players, like Gatorade and its derivatives Powerade and Exceed, along with most of the gels and bars, were all based on “science that may have been quite breakthrough in the 1960s, but which hadn't advanced or taken into account much of the new research.” With the right product, Portman believed, someone could take a pretty big bite out of the $2 billion sports-drink market.

A year later, PacificHealth invited Burke to a symposium held in April 1998 at Cheyenne Mountain Resort near Colorado Springs devoted to designing a new, high-tech recovery drink. Ivy was there, talking about carbs and protein. Others discussed the latest on free-radical damage, rehydration, and electrolytes. Just a month earlier, Burke had met with Barry Sears at a health-food trade show. “Sears complained that he had never trademarked the term 'Zone' or '40-30-30' and that everyone else was making money off his ideas,” Burke says. “I said, 'Aha!' and filed it away.” And so, hoping to avoid a Sears-like mistake after the Cheyenne symposium, Burke outlined the formula for a recovery-specific sports beverage and trademarked the name R4. He then licensed that name to PacificHealth for a flat fee, with the promise of royalties if sales ever took off.

Shortly thereafter came PacificHealth's magic potion—a recovery drink founded on the R4 principles, with added protein, a raft of antioxidants, and other ingredients, like glutamine, an amino acid, to enhance muscle-tissue repair and immune-system recovery. It slapped on a technical-sounding name, Endurox R4, and tested it against a standard sports drink. Sure enough, PacificHealth discovered the mix had all kinds of benefits, from increased endurance to decreased heart rate. As a bonus, Burke was able to include those results in Optimal Muscle Recovery, which was published just a few months later, while PacificHealth got to use testimonials from Carmichael (whom Portman had met just before Armstrong's first tour victory) and Burke in its ads. The revolution had begun.

Launched in April 1999, and followed later that summer with a marketing campaign that leaned heavily on Carmichael's role in Armstrong's first Tour de France victory, Endurox R4 caught the sleepy sports-drink market by surprise. With a label that served up some impressive boasts (“improves performance up to 55 percent and reduces postexercise muscle stress by 36 percent”), by the end of 2000 the beverage had made $2 million in sales. “It was hot,” says Reese Houghton, a buyer for the mail-order giant Colorado Cyclist. Large containers continue to outpace small ones in sales, Portman says, which indicates that committed athletes are favoring the product. That's critical, because Endurox R4 doesn't have much of a marketing budget and can't afford endorsement deals with big-name athletes. Instead, Endurox R4 is nurturing success via guerrilla marketing, giving free samples to athletes and relying on them for positive word-of-mouth. And it's working, says Portman. Many athletes are using Endurox R4, even though they're endorsing other products. “We may not have the little logo on the bottle,” he says. “But at this point, I just want to make sure we're in the bottle.”

On my third day I'm back in Burke's office, going over my fitness tests, the results of which fall somewhere between disappointing and devastating. Burke does his best to ease my injured ego, telling me I did better than any other journalists who have come through lately, except for the guys from Bicycling, who, he says, could have kicked my ass. OK, fine. Maybe I should give up cycling and pursue, say, exercise physiology. But not before I have at least harnessed Burke's nutritional strategy—which still isn't perfectly clear. I understand—at least as well as anyone who doesn't subscribe to the Journal of Applied Physiology—how these recovery products work, but I'm more perplexed by how, or even if, they fit into a daily performance diet for someone like me. Is it as simple as chugging Endurox R4 after every bike ride? Why, then, did Burke opt for a fried-chicken sandwich? What about my other meals? How much should I eat, of what, and when?

When I put these questions to Burke, he shunted me over to a colleague named Jackie Berning, a 50-year-old nutritionist-cum-den-mother who works with professional athletes from the Denver Broncos, the Cleveland Indians, and the Colorado Rockies. She is also a spunky, opinionated scientist who believes that many athletes, nutritionally speaking, are lazy, undereducated, and misinformed, and eat like spoiled children when given the chance. I liked her immediately.

Berning took me straight to the local Safeway. With bloodhound-like intensity, she worked the outside aisles first: breads, fruits, veggies, milk, eggs, and meat—your dietary staples. We stocked up on whole foods. We read labels on processed food to see how the calories shook out. And so on.

Berning's philosophy is a straightforward, food-pyramid-inspired balance of high carbs, low fat, and relatively low protein. Whole foods are preferable to processed; at least half your carbs should come from fruits and vegetables. It's not rocket science, although mapping out your dietary foundation does involve some basic math. And Berning agrees with Burke about the total caloric ratios outlined in Optimal Muscle Recovery—roughly 65 percent from carbohydrates, 20 percent from fat, and about 15 percent from protein. (For the record, Burke, Berning, and many other nutrition experts firmly dismiss high-protein, low-carb diets, touting carbohydrates as the primary muscle-fuel source—and the primary source for stimulating protein synthesis that rebuilds muscle after exercise.)

In practice, every day you should be getting about 3.2 to 4.5 grams of carbohydrate per pound of body weight, 0.8 grams of fat, and 0.5 grams of protein. Recovery meals should steer toward carbohydrates with a high glycemic index (GI), meaning they raise blood glucose rapidly. As your recovery cycle progresses toward your next workout, taper toward moderate- and low-GI foods (see, “Recovery by the Numbers,”).

I see you dozing. Well, rest assured, this is the only tough part; you cannot construct a performance diet without at least some analysis of what you are eating. But liberation is close at hand. You need to know your total daily caloric needs (I burn about 3,000 calories per day when training for about an hour and 45 minutes daily) and the ratio of carbs, fat, and protein in those calories, which can be calculated on a Web site maintained by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's . All you have to do is type in what you eat during a 24-hour period and follow the instructions. Depending on your level of seriousness, you can estimate portions according to the 65-20-15 ratios above (for a few tips, see “The Performance Grocery Cart,”) and let weight gain or loss be your guide. Putting on pounds? You're taking in too many total calories. Drop a pant size? Too few calories (which may be part of your goal).

If the science behind recovery is a bit complex, I've come to understand that a recovery diet boils down to something pretty damn simple: Don't miss the glycogen window after a workout, follow the 65-20-15 carbs-fat-protein balance, eat a wide variety of whole foods, and taper from high-GI foods after exercise to low-GI foods later in the day. I can chuck my pharmacy of supplements and protein powders; everything I need is at Safeway.

It's the last day of my visit and Burke is in his element. We're riding bikes in the Garden of the Gods, threading through a spectacular formation of red-rock pinnacles just outside town. A veteran of such two-wheeled spectacles as the Iditabike and the Leadville 100, the good doctor is schooling me up and down the hilly roads, spinning with an effortlessness I can only envy. He pauses at the crest of a climb, swigs from his drink bottle, and waits for me to catch up. “Hmm. Want my advice?” he says when I arrive. “Take two weeks off, then quit.”

I'm pretty sure he's kidding. But then, if I've come to understand anything about Burke, it's that, since his world is illuminated by the cold light of science, he calls 'em as he sees 'em. Which is not to say I'm entirely a lost cause. In fact, the reason Burke's recovery plan works so well is just this: In a fundamental way, he understands why our bodies fail during physical endeavor, and he knows how the foods we eat can help keep failure at bay just a little longer—perhaps long enough to win a marathon, or triathlon, or bike race.

That pragmatism is, in the end, what makes Burke and and his method so appealing. He can't change my genetics, but he has shown me how to enhance what I have, not just with expensive, complex formulas, but with a straightforward explanation of the way food becomes energy. In the weeks following my visit, I can tell you with certainty that this approach to recovery nutrition works, but it's helped me in other ways, too. I've come to be much less obsessive about my workout diet. I can miss a gram of protein here or a milligram of glutamine there. I'm training harder and feeling better, and the bike-racing season is just beginning.

When we wrap up our ride in the Garden of the Gods, I pack my bike into Burke's truck and begin rooting through my bag for a recovery snack—not of whey powder or a drink that tastes like TheraFlu, but maybe something a little less scientific, like a strawberry Pop-Tart. Only, despite being a Burke disciple for the last three days, I've forgotten to bring a single thing to eat or drink. He looks at me, and shakes his head. Burke doesn't need to say a word; I know exactly what he's thinking. When it comes to saving a world of tired, underfed athletes, the prophet of recovery has his work cut out for him.