On March 19 of this year, as the pandemic slowly gained steam, Canadian marathoner Malindi Elmore headed into an exercise physiology lab at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan Campus, in her hometown of Kelowna, with two pairs of very expensive shoes. Exactly two months earlier, the 39-year-old mother of two had with a third-place finish at the Houston Marathon in 2:24:50, a Canadian record and Olympic qualifier in just her second attempt at the distance. Doors had opened; wheels had turned. Elmore suddenly had options. But signing a shoe deal in 2020 is about way more than money—which is what brought her to the lab.

The clandestine launch in 2016 of Nike’s Vaporfly 4% racing shoes, featuring a carbon-fiber plate embedded in a thick layer of ultra-resilient foam, kicked off an age of extreme shoe anxiety among competitive runners. As the name suggests (and peer-reviewed lab data has confirmed), the original Vaporfly reduced energy consumption at a given running pace by four percent on average compared to the fastest conventional racing flats, speeding up race times for elite marathoners by an . To run in anything else was to grant your rivals a substantial head start, and the most of 2018 and 2019 were in-race snapshots of Vaporflys crudely painted in the colors of rival shoe companies by runners desperate to stay on a level playing field but contractually forbidden from doing so. Rumors swirled about contracts that were canceled over these photos.

Eventually, other shoe companies realized that World Athletics wasn’t going to rebottle the genie. They had no choice but to come up with their own thick-soled, carbon-plated models—and by the end of 2019, had announced its answer to the Vaporfly. Some were, well, carbon copies of the original, to the extent that Nike’s patent arsenal permitted; others seemed more slapdash, a shoe with a plate inserted just to say it’s there.

The most faithful imitator, painstakingly designed and other elite runners, appears to be Saucony’s Endorphin Pro. But whether it can actually stack up to the Vaporfly 4%—or its successors, the Vaporfly Next% and the Alphafly—remained unclear, because no company has released any performance data on their shoes since the original 4% study.

For Elmore, the situation presented a dilemma. As a track runner specializing in the 1,500 meters, she represented Canada in the 2004 Olympics, then narrowly missed both the 2008 and 2012 Games. In 2008, she was the fastest miler in the world to miss out, thanks to —a distinction that left a bitter taste in her mouth. After 2012, she retired from the track and turned to triathlons for fun while starting a family. She started coaching, both online and via a local club. She competed in two Ironmans, running the marathon leg in under three hours on fairly minimal training. Then, in the fall of 2018, with two kids and not enough time to train for three different sports, . With her husband, former Olympic 1,500-meter runner Graham Hood, coaching her, she decided to run a marathon. Four months later (and just seven months after the birth of her second child), she ran 2:32:10 at the 2019 Houston Marathon—in Vaporflys.

That’s when things got serious. With Tokyo on the horizon, she wanted to give herself the best possible chance of hitting the Olympic qualifying standard of 2:29:30, so she ran her 2:24:50 in Vaporfly Next% shoes that she’d purchased herself. But she had misgivings. “I don’t think Nike has done enough on so many aspects of doping scandals, women’s rights, and other social justice issues,” she says, “so I felt torn between wanting to run in the fastest shoes on the market and not wanting to financially support the company.” She hatched a plan to do head-to-head lab testing to figure out how much of a handicap she would face if she chose a different shoe.

Her record-setting run, meanwhile, had generated plenty of buzz. Saucony Canada’s newly hired general manager, Nicole McCasey, had been tracking Elmore’s return to competition, and also her influence as a coach and ambassador for the sport. “This is a very interesting combination: a mom to two young boys, passion for running, involved in the community in which she lives, and is chasing big goals,” McCasey says. Elmore, in turn, liked the fact that Saucony had several women in leadership positions, including McCasey. Saucony sent her a pair of Endorphin Pros to try out.

The Vaporfly’s claim to fame is its effect on running economy, which is simply a measure of how much energy you burn to sustain a given pace. It’s great to have a big aerobic engine, but you’re not going to be a great marathoner if you burn through your fuel like an . In the lab, you can estimate the energy you’re burning based on how much oxygen you consume. Running economy is typically measured in milliliters of oxygen per kilometer per kilogram of body weight. If you dip below 200 ml/km/kg, you’re pretty efficient. And whatever your value is, if you can slice four percent off it by changing shoes, that’s a big deal.

In consultation with , a well-known physiologist at the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific, Elmore arranged for two days of testing with exercise physiologist John Sasso at UBC Okanagan. She brought in a pair of Saucony Endorphin Pros and a pair of Vaporfly Next%, which at the time was the newest Nike model. She ran a series of short stages on the treadmill, starting at 14 km/hr (6:54 per mile, on pace for a 3:00 marathon) and progressing up to 17.6 km/hr (~5:30 per mile, 2:24 marathon pace), while breathing through a mask to measure her oxygen consumption. On the first day, she did the entire test sequence in the Nikes then repeated it in the Sauconys; on the second day, she did it the other way around to ensure the results weren’t skewed by fatigue.

McCasey knew about the testing plan. “Of course, there are natural nerves when Saucony’s lead innovation story, the Endorphin Pro, would be stacked up against our competitors by a third party,” she admits. Although no one has released any data publicly, the Next% is rumored to be another percent or two better than the original Vaporfly 4%—a formidable benchmark for the Endorphin Pro. But the results, it turned out, were a wash.

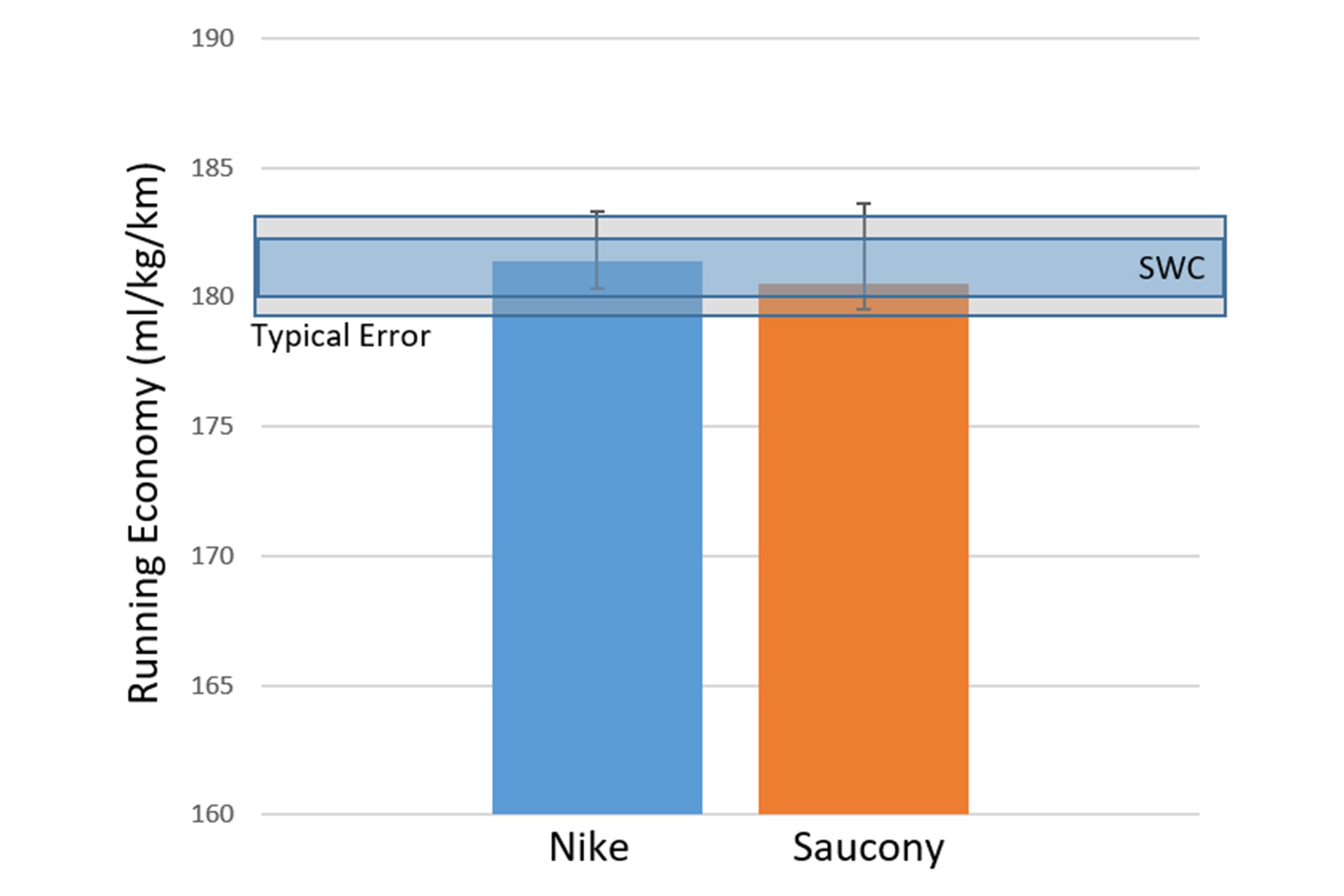

Here’s what the data looked like at 2:24 marathon pace, which is what’s most relevant for Elmore’s race goals, averaged over both days of testing:

You can see that the values are nearly the same: 181.4 ml of oxygen per kilogram per kilometer in the Vaporflys, and 180.5 ml/kg/km in the Endorphins. A lower number is better, because it means you’re burning less energy to sustain the same pace. But in this case, the 0.5 percent difference is much smaller than the “smallest worthwhile change” (SWC), which is a statistical measure of how much running economy values tend to vary between different runners. It’s also smaller than the “typical error,” which is a statistical measure of how much running economy values tend to vary when you test the same runner under the same conditions over and over. So the Endorphins are a tiny bit better numerically, but statistically it’s a dead heat.

That’s a big surprise. All those panicked runners painting their shoes were assuming that the Vaporflys had a big edge—which was probably true before rival carbon-plated shoes emerged, but may no longer be quite as big of a deal. That said, we can’t really generalize anything from Elmore’s results: everyone has their own individual response to each pair of shoes. Jos Hermens, the agent who represents both Eliud Kipchoge and Kenenisa Bekele, told me that Kipchoge got a big boost from the original Vaporflys, while Bekele got a much more modest one. For example, found improvements ranging from 1.7 to 7.2 percent in Vaporflys. It may be that Elmore responds particularly well to the Endorphins and poorly to the Vaporflys. Or not—maybe her results are typical. Without more widespread testing—something that’s hard to do with shoes that cost well over $200 a pop—we can’t say for sure.

For Elmore, the results were clarifying. She and her team acknowledge the limits of the protocol they used: a short run on a treadmill rather than a long and exhausting run on asphalt, for example. But it’s enough: while the pandemic delayed the process, she that she has signed a deal with Saucony (the details of which neither side will divulge).

As we approach the end of the year, when running shoe contracts typically start and end, other runners will be facing similar decisions. Will they follow Elmore’s lead and head to a laboratory? Stellingwerff told me that this is already happening, though he’s not able to reveal any names. Running economy is only one factor in any athlete’s decision, so no one wants to paint themselves into a corner by telling everyone about tests that end up suggesting their new sponsor’s shoes aren’t actually that great.

But it worked out for Elmore. And there was one additional bonus from undergoing the testing: she discovered that, despite her long career as a world-class miler, she might have been born for the marathon all along. Her running economy of 180 ml/kg/km at 5:30 mile pace puts her in elite company. At 6:00 mile pace, which is a commonly measured benchmark, it was even better: 168.4 ml/kg/km. That’s comparable to the value of 165 ml/kg/min at 6:00 pace that former marathon world-record holder Paula Radcliffe recorded (in pre-Vaporfly shoes, no less), which is the best measurement I’ve heard of for elite women, and among the best for either sex.

Elmore’s not getting ahead of herself, though. She’s still trying to figure out her next race—perhaps a half marathon in January to set up a spring marathon—while navigating travel restrictions and balancing quarantine requirements with the needs of her family. And although she was initially hesitant to reveal the results of her shoe experiment because of the pressure that might follow, she came around. “Just because my shoes say I can run fast doesn’t mean I will, unless I do,” she admits. “I think the older I get, the more I can shelter these thoughts and just stay focused on what matters: training hard, being consistent, recovery, and delivering performance.”

She also knows that technological progress hasn’t ground to a halt. She’s in a good place, with a brand she likes and a shoe that makes her one of the most efficient runners in history. But what if, I wondered in an email exchange with her and Trent, someone makes an even more economical shoe? “Okay, well…” she replied, “when/if it becomes public and if there is something vastly better, DON’T TELL ME!!!”

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book e.