The recent frigid temperatures hovering over the Northeast meant that my New Year’s Eve run was (as I ) a “three-sock run.” I was surprised to discover that quite a few people—even men—couldn’t figure out where the third sock would go. It was a reminder that dressing for winter running is an art born of hard-earned experience. Forget the third sock once and you’ll never forget it again.

In the ensuing conversation, a few whether I’d written any articles about the science of exercising in cold weather. —but the truth is that heat has received far more attention from exercise physiologists than cold. That’s partly because exercise itself produces heat that exacerbates the effects of hot weather and counteracts the effects of cold weather. Like an internal combustion engine, your body is 20 to 25 percent efficient at converting stored fuel energy into motion—so cycling at 250 watts generates about 1,000 watts of “waste” heat, while running six-minute miles produces about 1,500 watts.

Still, there are a few useful things to know about winter exercise—a bit of science and lots of trial and error that I’ve accumulated over the past few decades. If you get these details right, it’s entirely possible to exercise safely and comfortably outside in much colder temperatures than you might think.

Stay Dry

Everyone knows that, in theory, when exercising in the cold you should dress in layers that allow you to adjust your insulation level as needed. In practice, though, most people don’t actually add or subtract layers in the middle of a run. Instead, they throw on enough layers so they’re not too cold when they step out the door, start running, and pretty soon start sweating.

This is a problem because water has a far greater thermal capacity than air, allowing it to transfer heat by convection more quickly. That’s why it’s so easy to get cold while you’re hiking in a cool rain or swimming. Sweating doesn’t drench you quite that much, but even in high-tech permeable wicking clothes, you’ll still lose heat once you start sweating.

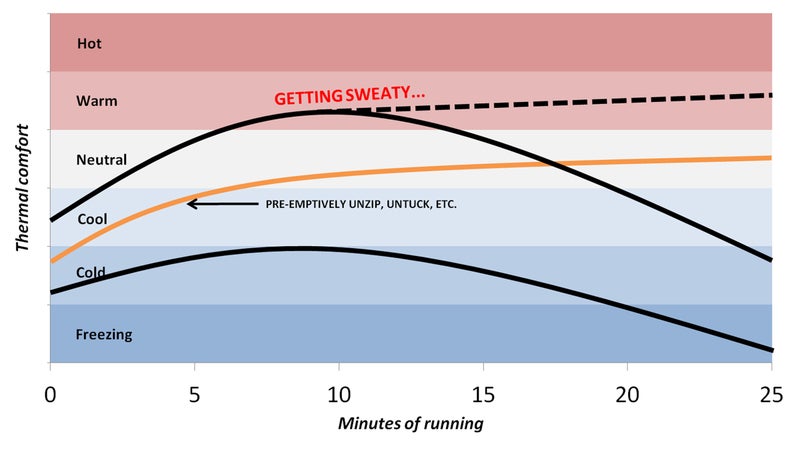

As a result, my personal approach to dressing for cold weather is to layer up so I’m uncomfortably cold during the first minute or two of my run. That first step out the door should be a mild shock to the system. Within a minute or two, if I’ve judged it right, I start warming up; within five or ten minutes at most, I should no longer feel cold. And here’s the key point: I start making adjustments—lower the quarter-zipper on my top, untuck my base layer—while I still feel mildly cool. There’s some lag time in your body’s heat level, so if you wait until you feel warm to start making adjustments, you’ll probably start sweating.

Here’s what my mental map of thermal trajectories during a winter run looks like:

The ideal scenario is the middle line, reaching a comfortable steady state in the neutral zone and continually making preemptive adjustments if I start to feel even a little warm or cold. For the most part, I finish winter runs with no accumulated sweat whatsoever in my running clothes. I’m not saying that I run in the same clothes day after day after day, but I’m not denying it either.

I should acknowledge that not everyone subscribes to this theory. I have running friends with just as much winter running experience who subscribe to a completely different philosophy. Why, they ask, would you make yourself uncomfortably cold for the first few minutes? They dress very warmly, sweat a lot, but are comfortable as long as they keep moving at a consistent pace and the wind doesn’t shift dramatically.

For relatively short runs of an hour or less, that’s reasonable if you don’t mind the feeling of sweaty clothes. For longer efforts, particularly if you’ll be stopping for breaks or having wide variations in effort or terrain (say, cross-country skiing in the mountains), sweat is a much more serious problem. It’s hard to stay warm during a lunch stop if you’re drenched, even if you throw on extra layers.

Mind the Extremities

The graph above refers to your core temperature. The extremities are a different question and can vary widely from person to person. My wife can run in thin gloves in the coldest temperatures, but her feet go numb; I need to wear fleece-lined boxing gloves even in spring and fall, but my feet rarely get cold.

The basic advice here is pretty obvious: Wear warm socks and mittens, and cover as much exposed skin as possible. On my New Year’s Eve run, the temperature was minus 11 degrees Fahrenheit, but the wind chill made it feel like minus 29 degrees. That’s significant, because once the wind chill dips below minus 17 degrees, you’re into the , meaning it can develop on exposed skin in ten to 30 minutes.

As for the old chestnut that you lose a large fraction of heat from your head—well, it’s true, at least under certain conditions. A found that at 25 degrees, if you’re dressed in winter clothes but your head is uncovered, half the heat you lose at rest will be from your noggin. To keep your brain warm, your body shunts warm blood away from other extremities toward your head, which means there’s a direct link between keeping your head warm and keeping your fingers and toes warm. And the same applies to your face: A found that wearing a face-covering balaclava resulted in measurably warmer fingers than wearing a normal winter hat.

Breathe Moistly

One last point to mention: You’re not going to freeze your lungs. As a Canadian military scientist (who should, after all, know) , the heat exchange mechanisms that warm up inhaled air are very rapid.

But that doesn’t mean deep-breathing super-cold air has no effects at all. Some people find that exercising in very cold temperatures triggers coughing, and elite winter athletes are more likely than the general population to develop exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, an asthma-like temporary narrowing of the airways. While this is still an area of active research, it seems likely that ; instead, it’s the fact that cold air tends to be very dry, which irritates the airways.

If you find that winter exercise triggers coughing fits, a simple thing to try is breathing through a light scarf, muffler, or balaclava, which will humidify the air you’re breathing. You don’t have to completely block your mouth—I have an old wool neck warmer that can sit loosely in front of my mouth, creating a little microclimate for the air I breathe without actually hindering airflow. There are also made specifically for exercise that can help humidify the air you breathe without adding too much breathing resistance.

The bottom line is that if you prepare appropriately, even severe cold doesn’t have to prevent you from getting outside. That’s the message I got a few years ago from Ira Jacobs, a physiologist at the University of Toronto who used to be the chief scientist at Canada’s defense research lab: “Under normal circumstances,” he told me, “it’s very rare for people to reach the limits of their cold tolerance if they’re appropriately dressed.”

Discuss this post on or , sign up for the Sweat Science , and check out my forthcoming book, .