Anyone who has scrolled through their own marathon race photos knows that the keen-eyed high-stepper who shows up in the early photos bears little resemblance to the pathetic hobbler of the final miles. Fatigue changes your running form, and yet the vast majority of biomechanics studies involve a few minutes on a treadmill at a comfortable pace. There are some exceptions (like this recent field study of marathoners at the World Championships), but much of our knowledge about running form assumes that we never get tired.

A in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, from a group led by Maximilian Sanno at the German Sport University Cologne, attempts to plug some of this gap. On the surface, the study was simple: 25 runners ran a hard 10K on a treadmill at a pace just five percent slower than their seasonal best time, and the researchers analyzed their strides at 13 different points (once per kilometer, plus right at the start and 200 and 500 meters into the run in order to capture the rapid changes as fatigue first hits).

The analysis, on the other hand, was anything but simple. The runners were decked out with 78 retroreflective markers attached to “bony landmarks” (places like the medial malleolus, the big bony bump on the inside of your ankle), whose motions were monitored by 13 infrared cameras; the treadmill belt had four embedded force sensors. All this data was analyzed by computer to assess the forces, torques, angles, and work done by each joint. That’s a ton of information, and experts can pore over the details to search for insights—but there’s one big trend that jumps out.

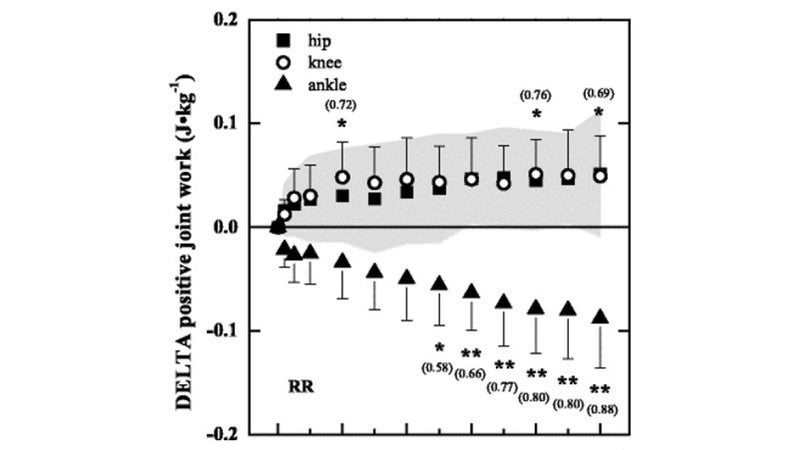

The key finding was that as the run progressed, the runners did less and less work with their ankles, and more and more work with their knees and hips. Here’s how the work done by each joint changed throughout the run:

This data is from the 13 runners in the study classified as “recreational,” with best times slower than 47:30. The pattern was the same in the 12 runners classified as “competitive” (best times faster than 37:30), but it was less pronounced in the faster runners, suggesting that they were better equipped to resist the fatigue-related changes. (As is unfortunately all too common in exercise studies, all the subjects in the study were male, so we’re left to guess whether the same pattern is observed in women.)

The reason this matters is that it’s well-established that runners get less efficient as they fatigue. By the time you get to the end of a marathon, not only are your energy stores severely depleted, but—in a cruel twist—it also takes more energy to sustain a given pace than it did when you were fresh. The reasons for this loss of efficiency aren’t fully understood, but the new data suggests two possible causes.

One is that the tendons in your foot and ankle are uniquely good at storing and returning elastic energy, basically giving you free energy with each stride as they stretch then snap back. As you begin to rely more on your knees and hips instead of your ankles, you benefit less from this energy storage capacity. The other possible explanation is that the muscles around your knees and hips are simply bigger than your ankle muscles, so they burn more energy for a given amount of work. Either way, the net result is that you get less efficient.

The obvious question, then, is whether you can stop the decline in ankle work. “In order to improve running performance,” the researchers suggest in their conclusions, “long-distance runners may benefit from an exercise-induced enhancement of ankle plantar flexor muscle-tendon unit capacities.” I got in touch with Maximilian Sanna to ask what that might mean in practice, and he directed me to that outlined a training program for ankle strength and tendon stiffness.

That particular program involved doing five sets of four ankle contractions (3 seconds on, 3 seconds off) four times a week. These contractions were performed isometrically, meaning that the foot didn’t move: it was pressing against an immovable resistance using a specialized machine called a dynamometer. Basically it’s like putting your foot flat on the floor and trying to press the front of your foot through the floor. It exercises roughly the same muscles as a calf raise, but stresses the muscles and tendons in a slightly different way.

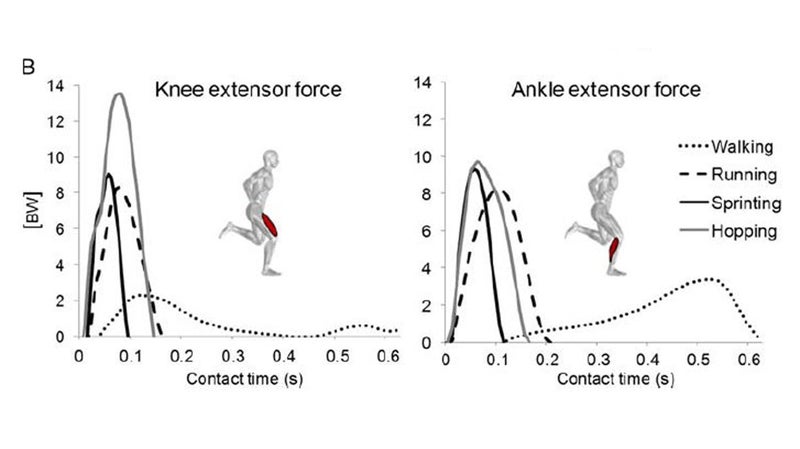

All this may sound a little random, suggesting that the secret to fast running is strong calves. But it’s not totally out of the blue. A few years ago, Finnish researchers published some data comparing how hard the knees and ankles have to work during running, and they compared these forces to the maximal forces produced during all-out hopping. While running, both knees and ankles generated a little less than 10 bodyweights of force. For the knees, that was much lower than the 14 bodyweights they produce while hopping. The ankles, in contrast, could only generate 10 bodyweights even while hopping: they were already nearly maxed out while running.

Here’s what that data looked like:

This finding—that ankles have to work relatively harder than knees during running—in turn helps to explain some earlier results from the Finnish group. They’d compared the gaits of three groups of runners with average ages of 26, 61, and 78. , all three groups produced similar power from the knees and hips, but the power produced from the ankles declined steadily with increasing age. The ankles, with relatively small muscles forced to work near their maximum capacity, are the “weakest link” as age-related muscle loss starts to kick in.

In a sense, the new German results echo the Finnish findings but on a different time scale. Instead of ankle muscles weakening over the course of decades, we’re seeing ankle muscles fatiguing over the course of a 10K run. That makes ankle strengthening look doubly smart—though it’s not really clear what the best approach is. When I asked the lead Finnish researcher, Juha-Pekka Kulmala, he mentioned standard exercising like calf raises and ankle presses. But he also noted that dynamic exercises like ankle hopping (hopping forward on your toes) are good for neuromuscular recruitment, and isometric exercises (like the ones Sanna recommended) are particularly good for your tendons.

Realistically, it’s probably too early to pretend we know what the optimal ankle strengthening routine is. But as results like this continue to accumulate, it’s worth making a mental note that your ankles may play a bigger role in your running than you realize. And perhaps the solution is as simple as what University of Colorado biomechanist Rodger Kram told me when I was writing about Kulmala’s research in 2016. “Personally,” he told me, “I just run hills.”

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .