IT’S A 90-DEGREE MORNING at the Medved Autoplex just south of Denver, truly a brutal place and time for the regional finals of the 2002 Scott Firefighter Combat Challenge. Sponsored by Scott Health and Safety, one of the top U.S. manufacturers of firefighter breathing equipment, this event is a preliminary to Scott’s World Challenge for firemen and firewomen, which is held every November and attracts hundreds of firefighters from all over North America.

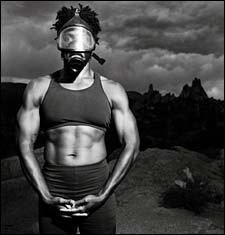

“Fitness is part of our sacred oath”: Juliet Draper at the World Gym in Colorado Springs

“Fitness is part of our sacred oath”: Juliet Draper at the World Gym in Colorado Springs Draper dragging rescue randy at the Colorado Springs training course.

Draper dragging rescue randy at the Colorado Springs training course. With Team Firejock members Stacy Billapando and R.C. Smith

With Team Firejock members Stacy Billapando and R.C. Smith “Watch me, Ironman”: Draper strikes a for-real pose.

“Watch me, Ironman”: Draper strikes a for-real pose.

ESPN, which broadcasts the Challenge finals, has labeled the competition “the toughest two minutes in sport,” and, looking around the parking lot, it’s easy to believe. Cars have been cleared to make room for a pair of five-story stair platforms, elements in a grueling pentathlon of obstacle-course events, each based on a firefighter’s real-life duties.

Today’s racers—some 100 men and two women, all wearing 75 pounds of firefighting gear—will have to lug a 45-pound hose pack up five flights of stairs; hoist another 45-pound hose pack, by a rope, to the top of a stair platform; drive a 165-pound steel I-beam with a sledgehammer; run through orange traffic cones to reach a water-charged hose, which they’ll drag 75 feet; and walk 100 feet backward, pulling a 175-pound dummy named Rescue Randy. All this while wearing masks and breathing from the bulky scuba-type air tanks firefighters carry on their backs.

Waiting their turn in the warm-up area are four Colorado Springs firefighters, one of whom—a loud, funny, buff, dreadlocked Challenge veteran named Juliet Draper—is telling the others what to expect.

“You’ll notice a lot of flexing, a lot of peacocking,” she says. “You’ll see the guys with the firefighting tattoos, playing the head game right here in the middle of the parking lot, making sure you notice them. A little later you’ll see them puking and suffering. Because you can’t avoid the pain.”

Juliet is a 36-year-old firefighter who won the Challenge in 1999, then took two years off to focus on paramedic school and recover from a leg she broke sliding down a fire pole. In 2002 she coached rather than competed, but make no mistake: She will be back. Juliet’s goals for 2003 include building oxlike strength to set power-lifting records this July at the World Police and Fire Games in Barcelona. After that, she intends—no, demands—to break the two-minute mark at the 2003 Challenge, a time no woman has really approached. Juliet’s best time is 2:34. Martha Ellis of Salt Lake City owns the women’s record of 2:22 but has temporarily retired from racing. She’s glad, she says, to hear that Juliet is still going strong.

To train for “sub-two,” Juliet will have to run endless stairs, build giant lats, and make not a single mistake out on the course, a skill she will hone, she says, by powering through the Challenge events until they appear in her dreams. She can talk about such goals without seeming cocky because, as many people in the firefighting community will tell you, she’s one of the best-conditioned female firefighters in the world. Perhaps the best.

“Boy, as an athlete, she’s scary,” says Colorado Springs deputy chief John Gibbons. “I’ve seen what she does in the gym and snuck out like a whipped dog. She’s a marvelous physical presence.”

Juliet is five foot nine and weighs 185, with the shoulders of an NFL wide receiver. She benches 250, squats 350, deadlifts 425. But such attributes are only part of what it takes to win the Challenge.

“Big, ripped guys and a skinny cat like that one over there—you won’t find out till later which one is faster,” she tells her team, pointing to a nearby group of racers and their friends. “And then one or two of these big gals, like that one with them big old legs…Hmm, why isn’t she competing? Could be the tit job holding her back? Anyway, for a chick, it helps to be the size of the average man. A small girl can do it, but a little ass helps you out. It ain’t your biceps gets you up those stairs.”

Standing in Juliet’s shadow is Stacy Billapando, a 39-year-old Colorado Springs firefighter/paramedic who’s due to race in ten minutes. A dedicated weight lifter and swimmer, Stacy stands five-ten and weighs 180, but her two previous tries in this race were unimpressive. She moves through the staging area silently, a look of sheer loneliness on her face.

“As a coach, my job now is to leave her alone,” Juliet whispers, jumping quietly in place to restrain herself from yelling a few final instructions. “She’s doing some mental rehearsing, she’s in a light sweat. She wants to break 2:30, maybe 2:00. I know she’ll go between 2:30 and 3:00.”

You might say Juliet is starting pretty small, coaching just three acquaintances. She’d never put it that way: At this moment, these three firefighters—who call themselves Team Firejock—might as well be the only athletes on the planet. Along with Stacy, the team includes Denny Peffer, a 50-year-old firefighter/paramedic who runs ultramarathons, and R.C. Smith, a 49-year-old battalion chief who definitely does not. Weighing in at 285, the chief is overweight enough that friends and colleagues call him, with much affection, The Fat.

“And every one of them will qualify for the nationals today,” Juliet vows. “That’s just the for-real.”

KEEP AN EYE OUT for Juliet Draper. Though her fame currently resounds only in the smallish world of fitness-obsessed firefighters, she has much bigger plans. Her current mantra is “I aspire to be the international voice of firefighter fitness.” Ask her to expand on that and she says, “There isn’t one, so it might as well be me.”

If this happens, a lot of the credit will go to Juliet’s live-in girlfriend, Pamela Jones, 49, a motherly schmoozer who, back in the eighties, promoted the meteoric career of her sister, new-wave diva Grace Jones. Pamela favors the all-encompassing approach to marketing the Juliet brand. In the past few years, she’s cooked up everything from a firefighter-fitness Web site () to a disco CD to promotional photographs of Juliet—naked except for a large African mask.

Will any of this turn Juliet into the next Tony Little? Does it matter? Whether she goes global or not, her message is worth hearing, and she’ll gladly shout it in your ear. It’s partly about her crusade to improve the fitness level of American firefighters, a group of people who—their deservedly heroic image notwithstanding—could use some help shaping up. But it’s also about Juliet’s quasi-religious conviction that fitness is good for the soul. Her own obsession with exercise, she says, saved her life. She coaches Billapando, Peffer, and Smith not just to prove the effectiveness of her training style but to inspire other firefighters to get up and move.

“I consider fitness to be part of our sacred oath,” Juliet says solemnly, “and not all firefighters are as buff as they look. We’re talking about guys who had it when they came on the job 20 years ago, but haven’t kept up. A great athlete at 25 needs to be great at 45, or what good does it do him when Grandma falls out of bed and she weighs 400 pounds and you have to put her back in?”

The firefighting lifestyle, Juliet points out, involves waiting for calls, which involves eating too much firehouse cuisine. (One classic dish, a concoction of ground beef topped with Tater Tots, is universally known as “grease pie.”) And even healthy brown-baggers like Juliet are not immune to the job’s crippling stress.

Studies bear this out: Firefighters are far more likely to die from a heart attack than a fire, and they exhibit greater indicators of heart disease than the general public. Wade Womack, an applied-exercise scientist at Texas A&M, conducted a six-year study of 74 working firefighters and found that “their aerobic capacity was lower than age-predicted norms, and their body fat higher. It has to do with a lot of downtime, with being sedentary. Once you’ve passed that fitness test to get on the job, it’s not necessarily done again.”

“When firefighters are first hired, they’re healthier than the general population, but they tend to retire less healthy than their peers,” says George Burke, president of the Washington, D.C.-based International Association of Fire Fighters, which has developed a voluntary firefighter-wellness program in recent years. “The leading cause of death in firefighters is heart attacks, not because these are big, fat, sloppy guys, but because they carry 75 pounds of protective gear and they do stressful physical work. They go from sleep to adrenaline in minutes.”

If someone gave Juliet a big whistle, she would attack these problems with megadoses of exercise and intense motivation. “It ain’t got to be Mount Everest every week!” she exhorts. “Just show up! What’s your favorite sport on TV? How ’bout you play football or baseball—or we can work on your golf swing. Why not? We’ll get a book! We’ll learn this together! Pick a sport!”

On a more basic level, she would institute regular, rigorous workouts, heated competitions—all departments duking it out against one another in the Challenge!—and mandatory yearly fitness testing, with results that could determine whether or not a firefighter stays on the force.

“Not a popular idea,” Juliet admits. “And I would not punish the guys who have been around and should be grandfathered in. But I would require new recruits to stay fit, and I’d test them.” Without testing, she says, “most of us in firefighting end up acting like regular folks, and time goes by and we begin to lose it.”

THE MEMBERS OF TEAM FIREJOCK won’t be allowed to lose anything. One day in mid-May, months before the Challenge regionals in Denver, the three assemble at the base of a five-story Colorado Springs Fire Department training tower that stands in a sparsely populated part of town. Scarred by burn marks, the tower smells like a barbecue gone wrong, but to Juliet it’s the perfect proving ground. The week before, she showed off to her trainees by pushing a pickup truck around the surrounding parking lot with her butt. (Helps develop ass.) Then she had them drag 45-pound weights around with chains, and run the stairs in full gear. This week, Juliet is starting in with new workouts that specifically mimic the Challenge.

Chief R.C. Smith, a.k.a. The Fat, has just run up the tower a few times, wearing heavy “bunker” pants and army boots. Now Juliet wants him to weave through the orange highway cones, moving as straight as he can, and fast. Halfway through, though, he runs out of breath.

“He’s a strong guy, a power lifter,” Juliet says. “But we need to work on his aerobic capacity. Excuse me a moment.” Stepping three feet away, she starts hollering: “Go, R.C.! Go, R.C.! Pick it up, FAST, FAST, FAST!”

The Fat, a little startled, picks it up.

“I didn’t even really hear what she was saying,” he says moments later, still red in the face, his trousers unfastened to make room for his belly. “Was it ‘looking strong, looking strong’? I hate that. And when it’s over, and I’m coughing up little bits of lung, she says, ‘Good job, R.C., looking strong!’ Please. I’m not looking strong. This whole thing might be easier if the Cheesecake Factory were involved.”

The Fat is here partly for his own benefit, partly in support of his friend Denny Peffer, who’s already plenty durable from his ultramarathon training. But short-term speed and agility have never been Denny’s strong suits, and today he’s having trouble perfecting the zigzag pattern required for running the Challenge’s cone course. If you get the order wrong, you have to go back and start over, losing valuable seconds.

“Watch me, Ironman,” says Juliet. She’s run the cones ten times already. She does it again without even breathing hard.

In recent weeks the unusual spectacle of Team Firejock has started to attract a crowd. Little boys line the chain-link fence bordering the lot. Today, two chiefs from other districts are also hanging out.

“I saw Juliet at the gym once,” one says to the other with awe, “and she stacked up this barbell and I thought, Shit, I never benched that much. It turned out she wasn’t benching it, she was doing some tiny little thing with her triceps. I didn’t even want to see her bench-press after that.” “She’s so strong,” the other guy agrees, “and she’s so small.”

“For a man she’s small,” his friend corrects. “For her, she’s…well, she’s her.”

WHERE DID JULIET’S Body come from?

“A mystery,” she says. “I was adopted. But they should have known. First thing I ever said to my father was ‘Juli run fast, Daddy! Juli run fast!'”

Growing up in the 1970s among Cleveland’s black middle class, Juliet made her parents very nervous. “I ran and ripped and punched boys and got in trouble,” she remembers. “I ended up having a huge, monstrous rebellion. A mohawk instead of Jheri Curls. New wave instead of R&B. I was the high school chick you don’t see in class because she’s out by the bleachers getting stoned.”

In 1984, during what was supposed to be Juliet’s junior year of high school, she dropped out for good, took up with a girlfriend, moved to a skanky part of town, and started delivering pizza to pay for pot, coke, and lots of alcohol.

“It was huge ghetto, huge drug people—more into substance than I was, if that’s possible,” she says. Eventually, it all led to crack and homelessness. After three years, Juliet checked into a shelter and started going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, at first more out of chronic hunger than moral awakening. She got clean, and she got fed. “They kept asking if I wanted more spaghetti,” she recalls fondly.

Her body responded. She started working out, thriving on gym routine—lift this much, rep that, continue until further notice. She joined the Army in 1990. In basic training, for the first time in her life, she felt at home.

“The Army takes people who don’t know shit and teaches them everything,” she says. “How you fold your clothes, how you balance a checkbook, how you eat. I did what they taught me.” The Army trained her as a firefighter, and in 1991 she transferred from Indianapolis to Fort Carson, in Colorado Springs, where she found the combination of adventure and rescue just right. Now that she’s a paramedic, most of her work involves emergency care. During one recent week, this meant dealing with a string of teen suicides, drug problems large and small, fatal car wrecks, and a trip to the state mental hospital at the request of a “sweet old black cat” whose much younger lover had gone off his meds.

Next, she intends to rise through the firefighting ranks. First stop: lieutenant.

“I want it,” she declares. “I’m a motivator. I have a love for the job. That can rub off on other people. It’s a team sport. It’s a lot of work. Hell, yes!”

She can live in the firehouse, no problem; be one of the guys; earn her place in the paramilitary pecking order. Hadn’t you noticed?

“Would you look at me walking down the street and say, ‘Hey, lemme go fuck with her’?” While you’re at it, would you goose her? A superior in the Army did that, not once but twice.

“Could have been a power thing,” she muses. “I asked him nicely if we could step outside. When we were alone, I said, ‘If you ever do that again, I’ll yank your balls off and shove them down your throat.’ He stopped. And see? He kept his dignity.”

THREE MONTHS AFTER Team Firejock’s training begins in earnest, their practice is interrupted by the worst Colorado wildfire season in recorded history. In mid-July, the southeast flank of the Hayman fire, which will go on to consume 134,000 acres, blows up not 30 miles from Colorado Springs. The Fat spends 14 days at a remote camp, where volunteer and paid firefighters can be seen sucking wind and surrendering their calm in extreme heat, just as Juliet would have predicted.

“It was the real deal,” says The Fat, grateful to have been under Juliet’s wing before hitting the backcountry. “You fight an urban structure fire, you go at 110 percent for 40 minutes. But wildland is aerobic: 14-hour days moving firewood, cutting fire lines, prepping houses. It’s continuous, arduous work with no breaks, and then you camp on the ground at night, eating food served out of drywall buckets.”

“If for no other reason than the level of stress, you should be ready for it,” says Juliet, who stayed behind to handle medical calls. “You’re away from your family for up to 21 days at a time, you carry all the stuff you need on your back, hiking all day. And that’s just getting to the fire.”

For everybody on Team Firejock, the summer is marked by steady fitness gains. Four months after the big blaze, by the time of the Challenge regionals in Denver, all three competitors are climbing stairs and swinging sledgehammers in their sleep. They’re sore. They’re worn out. They’re ready.

As the racing picks up steam at the Medved Autoplex, everybody tries to stay loose. The Fat steps very slowly up and down on a folding chair. Stacy’s about to go. Denny tries to extract a used wad of chewing gum from its foil. He likes to have a little spit in his mouth, he says, and this will help work it up.

On the other side of the course, competitors are finishing the race by falling onto a mattress, still clutching Rescue Randy. Whether they kicked butt or bonked, they now stagger into the recovery area breathless and/or nauseated, cooling off in a spray of water.

“All I want to do is finish,” The Fat says as he watches the racers come in. “I want it not to be memorable. I don’t want people saying, Remember when the chief got tangled in a hose? Remember when the chief puked?”

A small video crew wanders around, shooting atmosphere footage under the direction of Pamela Jones.

“They’re doing our fake Nike commercial, starring Juliet,” Pamela announces. When it’s wrapped up, she says, she’ll show it to Nike officials. After that, she hopes, maybe they’ll decide to shoot a real one. “And this is so great, we might be able to use it in our exercise video.”

Exercise video?

“Oh, yes, we’re definitely doing that now,” she says, holding a parasol over her head to keep the sun at bay. “We might tie it in with Firejock, or it might be a whole new thing. We’re still working on it!”

BUT THAT WILL HAVE TO WAIT. Just now, all heads are turning as Stacy takes off, racing against another female firefighter who posted a good time last year. The other woman tries to keep up with her. Big mistake. By the time she gets to the dummy, she’s staggering, falling, unable to finish!

Stacy, meanwhile, is magnificent, finishing in 2:41, a mark the P.A. announcer hails as the fastest women’s time in the U.S. so far that year. She’s definitely going to the big event in Florida. “Fastest chick in the USA!” Juliet shouts, jumping up and down, jabbing a finger at the crowd. “You heard him! In the USA!”

Behind Juliet and out of view, Stacy tries desperately to draw air into her lungs. She had hoped to break 2:30. But so what? She’ll have her chance in Florida.

Energized, Juliet runs off to find Denny, whose race is coming up. Having run the Pikes Peak Marathon the week before, he’s probably a little worn. Might be a good idea to slow him down.

As it turns out, Denny falls short of his goal—to break two minutes. But he ends up with a 2:38, a decent time that qualifies him to go to the nationals in his 40-and-over group.

Finally comes the big moment when The Fat starts his run in the not exactly competitive Best Chief category. (“Fire chiefs are not known for their physical prowess,” says Paul Davis, an exercise- science Ph.D. who created the Challenge. “We’re just happy if they show up.”) But with a time of 4:06, The Fat outperforms several other chiefs, fails to puke, generally emerges unscathed, and qualifies for Florida. He pulls off his coat and mask, revealing the usual flapped-open pants, and smiles broadly.

“That was hard,” he says.

“Good,” Juliet says. “We start training again in two weeks. Now it begins.”