Of the 43,000 runners in the New York City Marathon this fall, more than 6,800 were there for charity, raising a minimum of $2,500 to secure their spot on the starting line. That’s double the number of do-gooders who ran four years ago, with double the result: a record $24 million collected for about 80 causes from helping those with spinal-cord injuries to preserving the wildlife and culture of Kenya’s Masai tribal lands.

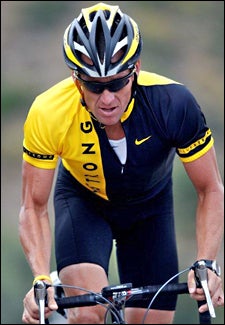

Lance Armstrong

Lance Armstrong

Lance ArmstrongThe impressive outpouring hasn’t been limited to the NYC Marathon. In 2009, Lance Armstrong’s four LiveStrong Challenge bike rides attracted 21,000 participants and raised nearly $11 million to support the fight against cancer. And Team in Training (TNT), started in 1988 and often credited with creating the cause-fitness model, raised close to $1 billion for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. In all, cause fitness is now generating hundreds of millions of dollars each year via walks, triathlons, mountaineering expeditions, stair climbs, table-tennis tournaments, and a raft of other activities.

What’s going on? When did America where selfishness and greed only recently crippled the global financial system get overrun by plodding platoons of philanthropists?

“One thing I can tell you: The landscape has definitely changed,” says Mary Wittenberg, president of the New York Road Runners, which stages the marathon. “We raised more money than we ever have in the middle of the recession.”

A big part of the answer is the way these organizations attract and motivate racers. For the past 40 or so years, psychologists have been investigating something called “self-determination theory,” or SDT, which seeks to explain the roots and intensity of human motivation: what, for example, pushes some people to perform better at their jobs, or drives an average person to get off the couch and run 26.2 miles. In 2008, a study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine confirmed SDT’s fundamental assertion, that motivation increases the more an individual meets three criteria: autonomy (you call the shots); competence (you measurably improve at what you’re doing); and, perhaps most important, “relatedness” (you have a purpose and connect with something larger than yourself).

This last point helps explain why cause fitness is often as successful for athletes as it is for charities. “Let’s say you have a reunion to attend and you want to lose weight to look good,” says Daniel Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. “Chances are you’ll drop the weight but it won’t last. External rewards and punishments, the carrots and sticks, are less sustainable over the long term than things that are more deeply meaningful.”

Take the example of Rachel Cowan, a 32-year-old quadriplegic who raised $17,467 in 2009 for the Challenged Athletes Foundation all so that she could then test her limits in the Qualcomm Million Dollar Challenge, a 620-mile bike ride from San Francisco to San Diego.

“It’s easy to bow out of something really hard if the only person you’re going to let down is yourself,” says Cowan, who has partial mobility in her upper body and rode a hand-cranked recumbent bike. “It’s a different story when you know others are counting on you.”

Or, for that matter, suffering alongside you. At TNT, which has attracted nearly 400,000 racers, an athlete’s sense of purpose may derive as much from assigned training groups as from fundraising target=s. “When you have to get up for those early-morning runs in the dead of winter, having a group pushing you really helps,” says TNT spokeswoman Andrea Greif.

If I’d been fuzzy on the conspicuous rise of cause fitness, a photo that Cowan sent me pulled it into sharp focus. In it, she’s nearing the top of a steep climb, cranking her three-wheeled rig while three other cyclists, on traditional bikes, ride behind her in an echelon, each with their hand on the back of the next person, providing a slight assist. That was it: the intersection of cause and community. “If I knew how hard it was going to be, I might never have signed up,” Cowan told me, “but you discover these like-minded people and the next thing you know you’re looking for a way to do it again.”