Horses Are Great, but Who Will Save the Wild Burros?

Horses may get all the attention, but burrosÔÇöaka wild donkeysÔÇöface the same threats of overpopulation and management issues on our public lands.

Mojave National Preserve

There are tens of thousands of free-roaming wild burros throughout the deserts of the Southwest. Many live on land managed by the Bureau of Land Management

Butte Valley, Death Valley National Park

Fortunately, there are organizations that care for the animals, places like the one I run, called Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue, which now manages nearly 2 million acres of federal burro habitat. Peaceful Valley is a nonprofit that doesn’t take taxpayer money. We have been rescuing donkeys for nearly two decades and have thousands of rescue cases to our credit. Our main facility is San Angelo, Texas, but we keep transportation and training centers in Virginia and Arizona, plus a nationwide network of adoption facilities. It makes us the largest equine rescue in the country.

Butte Valley, Death Valley National Park

Burros are not indigenous to North America, and with little predation to keep their numbers in check, they can easily overpopulate and damage fragile desert environments where they live. Keeping the population in balance means we need to remove some animals. This is done through bait and water trapping, which is a low-stress way to capture them and makes the transition to domestic life much easier. Then we give the burros microchips, test them for diseases, and enroll them into our adoption training program.

Saline Valley, Death Valley National Park

Burros and donkeys are the same animal—both names refer to the genus Equus asinus. Typically, the word “burro” is used for wild, free-roaming animals, while “donkey” is used for the domestic animals.

NASA Deep Space Communications Center in California

Burros are extremely protective of their offspring, and ranchers often them to protect their livestock from predators. Rather than a “flight” reflex, which animals like horses have, burros have a “fight” reflex that is often mistaken for stubbornness. In the wild, burros seldom run from danger but keep a wary eye to determine whether they need to defend against a threat.

Parker Dam, California

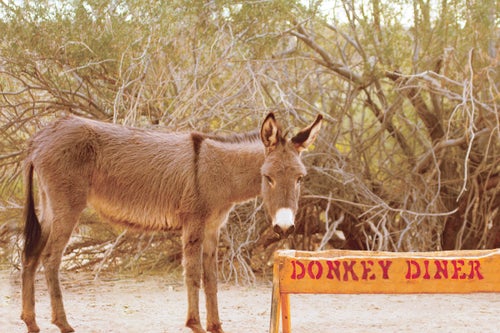

Burros are found in some of the harshest environments in our country. Many live in hard-to-reach areas well away from human contact and conflict. Some, however, choose to live in and around population centers. Parker Dam, situated between California and Arizona, is home to several hundred burros that have learned to rely on food given to them by humans.

Clark Mountain, Mojave National Preserve

Typically, wild burro herds are matriarchal, with female offspring staying with their mothers for life. Jacks (male donkeys) are forced from the herd at nine months to one year, a natural way to prevent inbreeding. These bachelor herds will stay together and return to the jennets (female donkeys) each year to mate.

Butte Valley, Death Valley National Park

Donkeys’ large ears are well suited to the harsh desert landscapes. Like jackrabbits and mule deer, those large ears help catch the faint desert breeze to cool the animal’s brain. Donkeys can survive five days without water—they’ll lose up to 30 percent of their body weight due to dehydration and gain it back in a short time the next spring. Experienced desert hikers know that all burro trails will eventually lead them to water. Burros have been known to dig four feet to find water, giving access to other species as well.

Havasu Palms, California

The burro may not get the same attention as wild horses and other large western mammals, but they are loving animals that also need and deserve our help.