This Is What ���ϳԹ��� Looks Like

Thanks to a bold movement led by activists and athletes, the outdoors at last is on its way to becoming a more inclusive playground. It’s about damn time.

My career in outdoor adventure began in 1989, shortly after I graduated from the University of California at Berkeley with a degree in anthropology. I took a minimum-wage job at the local gear shop, Recreational Equipment, Inc. At that time, there were about a dozen REI stores nationwide, gas was 97 cents a gallon, and my tuition was $850 a year. With a rent-controlled apartment near Telegraph Avenue, I felt like I had it made. I drove a Suzuki Samurai 4×4 with a gear rack mounted on the spare tire. With friends from work, I skied in Lake Tahoe and hiked all over the Sierra. I learned to climb in Yosemite. I raced triathlons and marathons. Life was good.

As an African American man in my early twenties, I defied convention to become a successful outdoor professional. In 1992, I landed a job at the North Face as an independent sales rep for a territory in the upper Midwest. Calling on shops in Milwaukee, Chicago, Minneapolis, St. Louis, Des Moines, Sioux Falls, and Fargo, I was the face of the brand in these cities for almost five years, and I went on to work for a number of other outdoor companies. Along the way, I encouraged people of color to participate in the activities I loved while pushing brands to grow their business by reaching out to people they’d long ignored. More often than not, my efforts were thwarted by dismissive senior executives. “James,” they’d say, “that’s just not our market.”

This assumption was rooted in the dominant cultural narrative about who enjoys adventure. Gear catalogs, advertising campaigns, films, and articles in magazines like ���ϳԹ��� typically presented the outdoors as a place for white people, most of them men. At the turn of the millennium, I decided to do something about this, pivoting from sales to journalism. I wrote about the achievements of people like the buffalo soldiers, African American members of the U.S. Cavalry who started patrolling Yosemite in the 1890s as some of our first national park rangers, and Sophia Danenberg’s historic 2006 Mount Everest climb, when she became the first black American to reach the summit. The more I looked around, the more obvious it became that the world of adventure was—has always been—far more diverse than we’d been led to believe. The stories of people of color, Native Americans, those with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ community just weren’t being shared widely in the outdoor community.

Finally, that’s changing. But not because the outdoor media and the outdoor industry woke up. What happened is that underrepresented groups took control of the narrative. Utilizing digital platforms, they’re speaking for themselves. Organizations like Outdoor Afro, Latino Outdoors, and Out There ���ϳԹ���s have begun stripping away the presumption of a white, male, heterosexual experience. Even more importantly, by unapologetically presenting their unique points of view, they’ve shined a light on a rich heritage of adventure and environmental stewardship that has been there for generations.

Many of these change makers are just getting started, their endeavors evolving as they adjust strategies and reassess goals. As they run, ride, paddle, ski, and climb throughout our nation’s public lands, they manifest a profound sense of belonging. Collectively, they are at the forefront of a rising national movement toward an inclusive outdoor community. They are the changing face of the outdoors. Here, in their own words, are some of their stories.

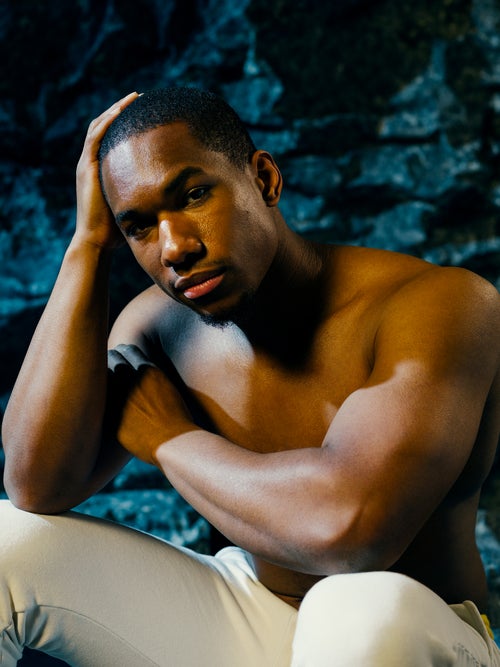

Photo: (from left) Ayesha McGowan, Knox Robinson, Shelma Jun, Krystle Ramos, Mikhail Martin

Danielle Williams, 31

Raleigh, North Carolina

Founder of Melanin Base Camp

I got into the outdoors through the military. I grew up an army brat—my dad was air-defense artillery, my mom was an army nurse. I jumped out of my first plane at age 20, when I was in Harvard’s ROTC, and was commissioned in the Army two years later. People think of skydiving as an extreme sport for adrenaline junkies, but for those of us who didn’t grow up hiking or climbing, it’s another way to appreciate nature. I started jumping recreationally in 2011, and that summer was magic. Every weekend I’d camp out at a drop zone with new friends. I moved to Alabama and traveled all over the South—Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Virginia, South Carolina.

A few years later, I met a small group of African American skydivers, all former military. We decided to set the unofficial record for the first all-black star-formation skydive, and from that Team Blackstar Skydivers was born. We got a logo and started to grow. We’re now 270 people in six countries—black, white, Latino, Asian, anyone excited about encouraging diversity in skydiving.

In the Army we have a saying, “Look outside of your foxhole.” Skydiving is my foxhole, and I wanted to learn about people of color in other adventure sports. So in 2016, I started an Instagram account called Melanin Base Camp as a place where we could come together Initially, the idea was to promote diversity in adventure sports, but as we got more popular I realized that what we really need to improve is representation. Storytelling matters, and we often get left out of the stories America tells about the outdoors. We need to challenge that—not to edge others out, but to demonstrate that people of different shades are out there.

Elyse Rylander, 27

Bellingham, Washington

Founder of Out There ���ϳԹ���s

I had my lightbulb moment in college. I was taking a queer theory class, and one day the professor invited two graduate students to talk about a writing space they’d created for LGBTQ kids. I’d noticed this disconnect between my queer friends and my outdoorsy friends, so being 20 years old and thinking I could change the world, I wrote my senior thesis about how to build an organization that gets queer kids into the outdoors.

After I graduated, I worked as a commercial wilderness guide in Alaska for a couple of years, then came back to Seattle and got to work turning my thesis into Out There ���ϳԹ���s. We received our nonprofit status in 2014, and ever since it’s been full-on trying to raise money and get programs going. Our courses are similar to what teens get in standard outdoor education, except that queers are in the majority. We also weave in time to talk about the nuances of being a queer person and how that gets reflected in the natural world. One of our sayings is “There’s nothing straight about nature.” Just look at the reproductive processes and life cycles of many plants and animals. Even the horizon line is slightly curved.

Most of our outreach is through presentations at schools and groups, and we’ve had more than 100 students in our programs so far. It’s rare for a young queer person to attend one and say, “I love going outside! I want to do it all the time!” They come because it sounds fun. Then they get there and the magic happens. They see adults and kids who look like them doing this. That’s a profound experience for youth who’ve been told that there’s a specific way that you need to be in order to be a part of a community. After an afternoon of climbing or backpacking or sea kayaking, they walk away with a different sense of self.

Knox Robinson, 43

Brooklyn, New York

Cofounder of Black Roses NYC

I tie everything I do to culture. It’s my frame of reference. Rather than thinking of running in an empirical sense—heart rate, finishing times, personal best—I think about the fabric of what keeps us enraptured by what is a pretty basic pursuit.

My dad did the occasional 10K or half marathon on weekends. I grew up believing that this was one of the tenets of a man’s life. I started running in high school. Edwin Moses loomed pretty large back then, and I thought I was going to be a hurdler, but that didn’t pan out. I was into distances early on, mainly because I was so slow.

We started Black Roses NYC as a membership-based running collective. We are performance oriented, but we’re grounded in New York City street culture. We believe that running can be a connective force in our communities. Running to a bar or a dim sum restaurant in an outer borough is as important to us as training. Our name comes from a reggae song that was popular in the nineties. We love the provenance of the tune—it’s a dancehall classic. On a thematic level, we celebrate the idea of the rarest flower in the garden, the one you never see. It speaks to people of African descent, but I have no problem with people from other backgrounds running in our group and enjoying the mix we create.

We must consistently endeavor to support and even proselytize the image of black health. That’s crucial. We need to talk about cardiovascular-disease rates, but also mental and emotional well-being. Running is a bedrock for health. Moving unfettered through space, in our communities or on trails—on a good day, it’s the very essence of freedom.

Mirna Valerio, 42

Rabun Gap, Georgia

Ultrarunner

My freshman year in high school, I decided to try field hockey. I had never been on a team or done anything physical outside of PE class other than play with my friends on the streets of Brooklyn. Now I was at this all-girls boarding school, and the first day of tryouts began with a mile run. That was a shock to my system. Then we had to do a timed mile and two and a half hours of drills. It was so painful, but joyful at the same time. I began running early in the morning before practice. I loved it. My size was never an issue. I ran to get stronger.

After college at Oberlin, I moved back to New York and started entering road races. I took a running class. In 2011, I ran my first marathon. Two years later I did my first ultra, and I’ve run nine others since. I’ve failed to finish some races, including the 2017 TransRockies Run, which is a six-stage, 120-mile event in Colorado. I made it through two stages and over 12,540-foot Hope Pass, but I was going so slow that I pulled myself out. I decided to go at whatever pace I wanted and take pictures. I’ll definitely go back.

I have a huge following now on Instagram, and people come to me with questions or encouragement. There’ve been negative things written about me, too: some folks say that because of my weight, I’m not really an athlete. They’re writing this literally while I’m running marathons and ultras. My message is be active with the body you have. I think what bothers some people is that I’m unapologetic. We live in a society of expectations and norms, and people can be threatened by something that’s different. But I continue to show them. I show up—for myself and others.

Mikhail Martin, 28

Queens, New York

Cofounder of Brothers of Climbing

At first we were just some black dudes who climbed. There were about five of us, and we’d see each other at the Brooklyn Boulders climbing gym, where almost everyone else was white. I grew up in Queens, which is one of the most diverse places on earth, so when you come from that and go into a space that’s very homogenous, you’re like, Whoa! What’s going on here?

Somehow that turned into Brothers of Climbing. We’d be at the gym and call out to each other: “BOC! BOC!” We didn’t have a plan, but we knew we wanted to do something. We set up makeshift competitions. We made BOC T-shirts. We wanted it to be a talking point, for people to ask us, “What does that mean? What are you about?” The answer when we first started was that we wanted to see more black people in the sport. As time went on, we realized that it wasn’t just black people. A lot of different groups have been left out.

Fast-forward to today and we’re doing events and meetups that allow people to come into the gym at a lower cost. In New York City, a day pass is $30, which is crazy. And that doesn’t include gear rental. We’ve partnered with Brooklyn Boulders to put up a climbing wall at Afropunk, a huge art and culture festival in the city. We partnered with Brown Girls Climb to create Color the Crag, a gathering that celebrates diversity in climbing.

If we can at least give new people the opportunity to try the sport, we’ve done our job. People of color are trendsetters in other areas of pop culture, and I think the same will happen in climbing. We just need to create a gateway to bring in a little soul.

Shelma Jun, 35

Brooklyn, New York

Founder of Flash Foxy

I was born in South Korea, which has a big culture of hiking and camping. My family immigrated to Orange County, California, when I was five, and on family vacations we mostly drove to national or state parks, mainly because it was affordable. I was introduced to adventure sports in high school. But it wasn’t until a period of recovery following shoulder surgery that I got into climbing. I wasn’t able to do anything where I might fall on my shoulder, and a girlfriend invited me to the climbing gym. You can’t really fall if there’s a top rope.

I got my master’s in urban planning at UCLA and came to New York to start my career, taking a job at an affordable-housing nonprofit, then an organization that works in commu-nity-based design. I also found an amazing crew of women climbers, and in 2014, I started an Instagram account called Flash Foxy to post pictures of us. The idea was to celebrate women climbing with other women. We got a lot of positive feedback, and thousands of people began following us. It was exciting, because conversations around diversity in the outdoors weren’t really happening back then. But I had an organizing background, and I felt like I needed to act on the potential to move things forward. So we started the Women’s Climbing Festival. I thought it would be 40 women hanging out in the eastern Sierra. But when we announced it, about 300 women wanted to attend. A few months later, I quit my job. The 2017 festival sold out in under a minute, and we had 800 women on the wait list. This year we’re putting on events, clinics, and trips across the country.

The more women there are in climbing, and the more diversity, the better the sport will be. It’s going to create a richer culture. I’m excited to see that play out.

Len Necefer, 30

Denver, Colorado

Founder and CEO of NativesOutdoors

I come from the Navajo Nation. My family is in Arizona and New Mexico, and they are traditional healers and farmers and ranchers. A lot of my early outdoor experiences were passing time while herding sheep. We would scramble around, look for medicinal plants, and dig up roots. When I went to college in Kansas, I started mountain biking and trail running and climbing. But I found that so much of the outdoor community’s relationship with nature was about conquering it. That felt empty. I grew up with practices that are based on an ethic of reciprocity with the land. Everything you take, you give something back. We were also taught the history of places through stories that have allowed us to live in them for thousands of years. We weren’t just out there to have fun.

For my doctoral research, I looked at how cultural values toward the environment inform our preferences for energy resources like solar, wind, and fossil fuels. Later I worked for the Department of Energy on policy and technical assistance in Native communities. One of my biggest takeaways has been that culture plays a significant role in our relationship with the outdoors and land management, and it is often unquestioned. That understanding motivated me to create NativesOutdoors, which I launched in March 2017 with an Instagram account, sharing photos of Native people engaging in outdoor sports. I wanted to normalize recreation in my community, because the prevailing imagery out there does not include us. The platform has evolved to include storytelling by Native people and geo-tagging social-media posts of adventures with indigenous place names in order to start conversations about the history of an area.

If we can get more Native people participating in outdoor sports, we’ll bring our values of stewardship with us. Within my community, I’m an advocate for recreation as a vehicle to learn about the land and carry on our traditions.

Rue Mapp, 46

Oakland, California

Founder and CEO of Outdoor Afro

In the beginning, the idea was to share our experiences with a blog and a Facebook page. Because of my art history background, I understood the power of stories and images to change narratives. I’d been the only black person on a lot of hikes and camping trips, something that many African Americans have endured. It gets tiring. We asked our audience about this, and we listened and grew. Over time we crafted an organization that evolved into, How can I find other people like me who like to do these things? We’ve trained more than 60 volunteer leaders in 28 states who connect thousands of black people to the outdoors through recreational activities.

The thing that really surprised us was how we enabled everyday folks to see their leadership potential. That turned out to be such a gift—a rolling wave of blessing not only for our organization but for individuals who now have an outdoor identity. It can be “I’m an architect and an outdoor leader,” or “I’m a real estate professional and an outdoor leader,” or “I’m a preschool teacher and an outdoor leader.” We’re really helping people to say, “I’m someone in my community who can create change. I can be supported in this network to be more fully who I am.” That’s exactly what happened for me.

Krystle Ramos, 31

Los Angeles, California

Director of programs for Community Nature Connection

For me, going outdoors is about being with family. In the Latino community, we want to share experiences with the people closest to us. When I was a kid, we focused on that instead of anything competitive, like getting to the top of a peak. My father worked in the parks and rec department in Los Angeles, and he always knew where to go.

In college I started heading farther into the mountains, and after graduation I got a few jobs taking kids camping. Pretty soon I was working for 11 different companies, traveling all over the place. In the summer I led trips in Thailand and Costa Rica, and the rest of the year I was in the Santa Monica Mountains, the Los Padres National Forest, Joshua Tree National Park.

At Community Nature Connection I do similar work, but as a decision maker and with more resources. Our goal is to bring underrepresented communities into the outdoors, both as visitors and as part of the workforce. We offer field trips for schools, public day programs, overnight camps, professional development, and rides to the beach or mountains to eliminate transportation as a barrier. Our staff reflects the diversity of the communities we serve. Last year we reached 6,600 people in the Los Angeles area. For many, it was their first time camping or seeing the ocean.

With new staff, a big part of our training is helping them understand that our job is to provide experiences that our audience wants. That means being flexible. You might want to build programs around trails or big physical objectives, but people need to be allowed to spend time in nature in their own way.