Op-Ed: Jimmy Carter Created an Environmental Legacy

In sharp contrast with today's administration, the 1970s were a time when our environment was seen as valuable and not a resource to be destroyed and turned into dollars

It was the early 1970s. Georgia’s new governor, a young man by the name of Jimmy Carter, was a breath of fresh air in the capitol. He was following the administration of Lester Maddox, a governor so bigoted that he threatened to “defend” his restaurant, Atlanta’s Pickrick, from black customers by wielding ax handles.

Well traveled as commander of a U.S. nuclear submarine, Carter had come to appreciate the similarities and basic rights of people far beyond our own borders. And just as important, he was learning how the environment makes possible our very existence on this planet. Growing up with a knowledge of sound farming practices and the need for clean water and air led Carter to explore policies—both on a state and national level—that affect our quality of life.

During this time, I was working as a river guide and met Carter when I took him canoeing, kayaking, and rafting on three trips down the Chattooga River.

The Chattooga in the late 1960s was little known beyond our small group of Atlanta paddlers, who appreciated the challenge and solitude it offered. Born near the sheer face of Whiteside Mountain in western North Carolina, the river plunges through laurel and rhododendron so dense that sunlight rarely reaches the cascading water.

As the river approaches eastern Georgia, the rapids take on a deeper, more ominous roar. Towering cliffs at Narrows and Raven Rock, and vanishing horizons as the intimidating drops of Five Falls descend toward Lake Tugaloo, give the paddler pause. But overriding all else is the eerie feeling that you have stepped back into a world untouched for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.

A natural boundary between Georgia and South Carolina, the Chattooga cuts its way through country so wild and rugged that no engineer has ever been successful in forcing a highway or railroad through its gorges. We knew, even in 1968, when Congress passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, that the Chattooga undeniably qualified for such protection, though it would take years to be protected.

The Chattooga was largely unheard of, a mysterious backwoods beauty unknown to those who had the power to advocate for its inclusion at the national level.

Meanwhile, the country was waking up to the concept of high adventure on rushing rivers. Idaho surgeon Walt Blackadar was rushing across TV screens on Wide World of Sports as he ran the Susitna, Alsek, and other intimidating Alaskan rivers. The 1972 Olympics in Munich included whitewater slalom as an event for the first time.

Then, late in the summer of 1972, the critically acclaimed adventure thriller Deliverance appeared in theaters nationwide, convincing some moviegoers that they would never set foot in the South and spurring others to challenge the very river where the filming took place: the Chattooga. They came. By the hundreds. With cheap department-store rafts, cases of beer, and little or no whitewater experience. Within the first two years after the release of Deliverance, more than a dozen people died in the rocky turbulence of the river.

Several of us stepped in to create commercial rafting companies, and the Forest Service met with area paddlers to establish safety requirements for running the river. Fatalities on the Chattooga became less likely. But try as we might, Wild and Scenic Rivers protection remained elusive, and the river was in danger of being destroyed by overuse.

Enter Jimmy Carter.

Georgia’s governor had seen Deliverance at its Atlanta premier in 1972, felt the pull of the Chattooga, and through the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, made contact with Claude Terry, a microbiologist at Emory University. Terry quickly set up a trip for the future president on an intermediate section of the river, contacting eight friends who were skilled canoeists to serve as guides, each bringing a boat with space for a guest paddler. I was one of the guides.

That year the weather smiled and the river flowed at an optimum level. Carter, his son Jack, and staff friends part of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources felt both the beauty and challenge of the trip down the Chattooga.

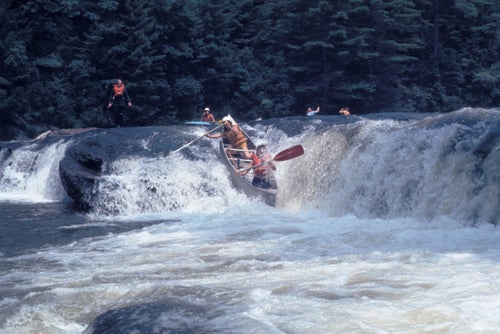

After all the other pairs had portaged their canoes, the governor, with Terry as his partner, made a successful descent of Bull Sluice, a formidable plunging, twisting rapid rarely attempted by tandem open-canoe teams.

Carter would return the next year running a solo kayak, having practiced rolling with us during the winter at the Georgia State University pool in Atlanta. His lines were precise, and he never needed his newly acquired roll. We were also impressed by his candor as he spoke of his successes and failures as governor and described his plan for the country as president, even though the election was still three years to come.

When he returned the following year, after that winter practice at Georgia State, Carter wanted the whole challenge—the most difficult whitewater the Chattooga could offer: the rapids featured in Deliverance. We were be happy to oblige. As had been the case on his two previous trips, he came not for publicity but because the river was dear to his heart. No photographers or state troopers accompanied him. Only his wife, Rosalynn, was by his side. They would run this section of the river by raft, a prudent choice.

Rosalynn would prove herself once more. When their guide missed his line at Seven Foot Falls, standing the raft on edge in the precipitous plunge, it was she alone who held her position, retrieving the others from the churning water below.

Less than a year later, in May 1974, the Chattooga officially became a wild river under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Many folks worked tirelessly, but it was largely the advocacy of Jimmy Carter that made the protection possible.

It was during his years as president that Jimmy Carter was able to have the greatest impact on the environment of our nation. He successfully de-authorized 16 water-reclamation projects in an effort to restore natural water flow and keep the rivers as they should be—wild.

Before leaving office, Carter designated, along with a host of national parks and monuments, 25 new Wild and Scenic rivers in Alaska, more than doubling the total number as well as the total mileage of all Wild and Scenic rivers. It’s a legacy that may well remain unmatched.