This National Park Art Has an Important Message

More than 50 national parks host visual artists every year. These three artists used their residencies to draw attention to climate change, species loss, and pollution.

The earliest known records of our national parks were made with oil on canvas, pencil on paper, and old film cameras. Some of the National Park Service’s most popular units, including Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Grand Canyon, became federally protected in large part because of artists documenting their pristine beauty for the public.

That artistic legacy is a pillar of the national parks in modern times as well. The NPS continues to hold more than 50 artist-in-residence programs at parks and monuments across the country. Residents can be visual artists or musicians, and they stay on the grounds for several weeks or months while creating work based on their surroundings.

Now, more than 150 years after visual artists first made the case for conservation, a handful of contemporary NPS artists are using their residencies to combat threats to public lands. We spoke to three who recently used their time at Zion, Joshua Tree, and Denali national parks to highlight what will be lost if climate change and public land rollbacks continue uninterrupted.

Mariah Reading

Mariah Reading paints reclaimed pieces of trash found in national parks across the country and then photographs them in the location where the object originally was. Her 2018 residency in Denali National Park created work to highlight a groundbreaking zero-landfill, recycle-only initiative. Reading wanted to use her time on the ground to showcase the ways people came together to keep the park “wild and beautiful.” She says it’s the cleanest park she’s ever visited.

Photo: This crushed Pabst Blue Ribbon beer can was the only piece of modern-day trash Reading discovered in the park during her ten-day residency in Denali, which reinforced her belief in the park’s recycling efforts. “It was crunched up almost like one of the rocks on the stream where I found it,” Reading says. “I like that exchange between the trash and the landscape.” Reading noted, though, that the park isn’t completely free of garbage: as its glaciers melt (and they’re melting fast), long-forgotten detritus that had been covered by ice has started to reappear.

After finding this keyboard discarded at the E-waste Recycling Center in Denali, Reading decided to paint the surrounding landscape onto it and titled it Fireweed Keyboard. “These pieces of recycling can have footprints even after they’re discarded properly,” she says.

As Reading drove back from Wonder Lake to her cabin one night, a vivid alpenglow stopped her in her tracks. She felt inspired to document the magical light and did so in her usual medium: by gathering the trash she’d accumulated in the backcountry to create a collage. “I really like the spontaneity of my work,” Reading says. “It’s almost like improv each time I go out and paint.”

Zoe Keller

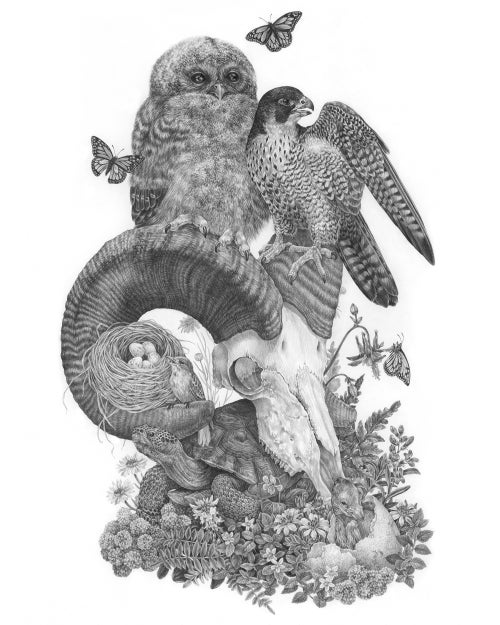

Zoe Keller’s meticulous graphite drawings make even the scaliest creatures seem beautiful, and that’s the point. She hopes that showing the value of all species—not just charismatic megafauna—will help to spark a conversation about at-risk wildlife. “I might be a part of the last generation of artists that will be able to draw these species while we’re still sharing the planet with them,” she says.

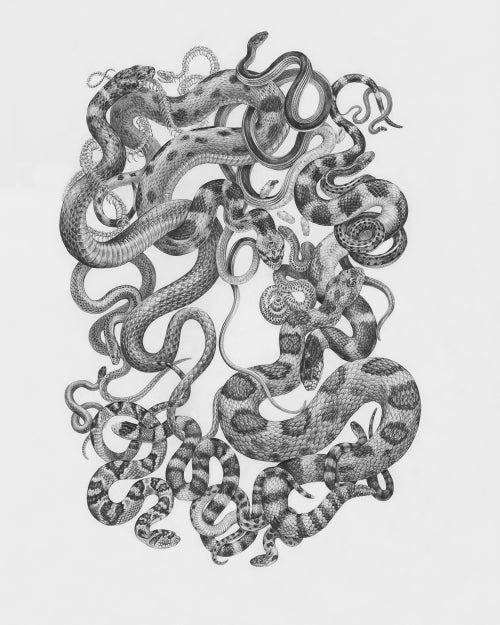

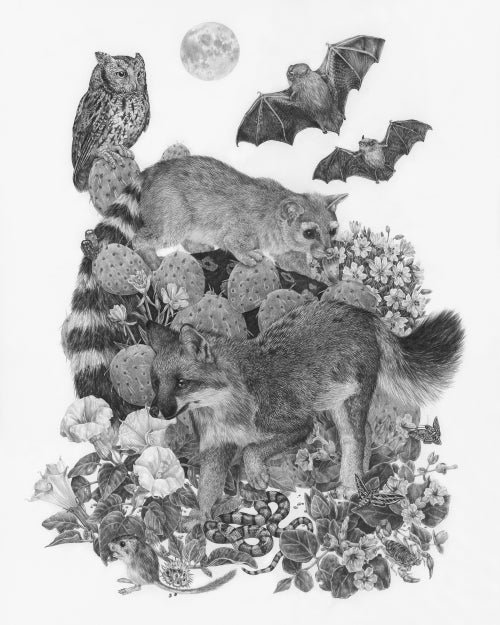

Keller began drawing with graphite pencil about five years ago. She loves that the medium encourages her to learn about the animals in exquisite detail. During an NPS residency in Zion in 2018, Keller’s work featured the park’s snakes, songbirds, and plant species. This year, she will complete a residency at Acadia National Park in Maine, where her drawings will focus on its diverse varieties of lichen.

Illustration: This drawing highlights species that have been close to extinction in Zion, with particular emphasis on the head of a bighorn sheep. Keller joined the park staff during their research and observation of the sheep. “Climate change is not good for any of them,” Keller says of the species in this drawing. “But there are also a lot of different pressures, like habitat loss or spread of disease from domestic livestock and animals into wild animal populations.”

In capturing the beauty among 13 snake species she observed in Zion, Keller hoped to encourage people to reassess their fear or dislike of the slithering creatures. “Snakes elicit such strong reactions from the viewer,” Keller says. “I think examining that reaction can be a really interesting way of thinking about how we relate to other species.”

Keller says the best way to learn about a species is to observe it, though that’s easier said than done when dealing with species after dark. This drawing, Zion at Night, showcases animals seen mostly after dark. “The idea that the park came alive with a whole new cast of characters after I went to sleep in my cabin made me so curious about what I was missing as a diurnal mammal,” Keller says. During her residency, she donned night-vision goggles in the hopes of spotting the infamous ringtail cat.

Juniper Harrower

Juniper Harrower’s abstract paintings and stop-motion animation highlight a devastating truth: climate change is killing the beloved Joshua tree. During her residency in 2019, the ecologist and multimedia artist created an animated short called A Joshua Tree Love Story, which explores how climate change affects the symbiotic relationship between the trees, root fungi, and pollinating moths. The film shows Harrower journeying through the park with her infant son and reveals that the trees are running out of time. She artfully makes them go extinct as her baby ages into an old man: “Species loss can occur within a human lifetime,” she notes.

Harrower grew up near Joshua Tree National Park. She never expected that she would dedicate a majority of her life’s work to the region. But the destructive impact on her backyard diverted her plans. “Climate change and species loss is happening with all kinds of organisms that nobody cares about,” she says. “But Joshua trees are so iconic, so people pay attention.”

Photo: This still shot, taken from a scene in A Joshua Tree Love Story, captures the yucca moth’s vital existence to the tree’s ecosystem. Harrower’s 2018 research found that the moths’ health is deteriorating and trees are not reproducing in cooler parts of the park as a result—which will make it challenging, if not impossible, to survive climate change.

Harrower’s own abstract pieces provided inspiration for the stop-motion’s painted sets. This example, titled Mid-Elevation Joshua Trees, is a depiction of trees found at her field sites. It is made with acrylic paint, ink, alcohol, and a special ingredient: “I would extract an oil out of Joshua tree seeds and mix that into my paint to get these textures and really organic shapes to evolve,” Harrower says.