Meet a Village Grappling with Climate Change

A small Arctic community is at risk of getting submerged by the sea. The biggest problem? It's too expensive to move away.

On a stormy day in August 2017, my boss and I landed on a tiny barrier island off the northwest coast of Alaska. Amy Martin and I were reporting for the second season of Threshold, a podcast and radio show that tackles one pressing environmental issue each season. This season is all about the Polar North and features reporting from all eight Arctic countries. But instead of ice sheets and polar bears, we’re starting with people. Four million people live in the Arctic, and we’re looking at climate change through their eyes to understand what the Arctic is, how it’s changing, and why those changes matter to all of us.

That day in August, we were in a predominantly Iñupiat village called Shishmaref. The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and the 600 people here are living at the front line of climate change. Due to warming temperatures, the sea ice that surrounds the island forms later than it used to each year. This means waves from fall storms swoop in to batter the land itself rather than the blanket of ice around the island. Each storm takes chunks out of the coast. In 2005, one of those torrents hit the island. Photos of houses precariously perched just above the raging sea showed up in news outlets around the world, and Shishmaref became a poster child for climate change. In 2016, residents voted to relocate—the final tally was 94 to 78. But doing so is expensive; people here lack the money to make the move, and the government hasn’t allocated the funds. So life goes on here despite the risk of deadly storms each fall.

The climate isn’t the only thing changing in Shishmaref. To find out more about the village, I joined Amy on the island with a big fuzzy microphone in one hand and a camera in the other.

Photo: Brent and Elmer weave between boats on the shores of the island. The late-night and long-lived summer sunset blazes behind them, but their eyes are fixed on the ground, not the sky. On the other side of the island, a five-minute walk away, waves slurp at the seawall. It’s summer now; in a few months, ferocious fall storms will blow in.

Under the sunset, boats sit idle on the inland side of the island. One side of the island faces the open Chukchi Sea. The other side is just five to ten miles from the mainland. You can walk across the island in a few minutes. Many residents here have camps along the nearby Serpentine River, and boats are a key means of transport in the summer months. No roads run to Shishmaref, which is largely a subsistence economy, meaning residents rely on hunting, fishing, and gathering for much of their food. Climate change affects the behavior of the marine mammals that people here depend on for food. Walrus, for example, migrate farther from shore than they used to. For hunters, this means more time and resources to collect food—and a more dangerous journey to get there. It also means centuries-old knowledge of ice is less and less reliable.

Shishmaref resident Nora Kuzuguk, 70, recounts stories she heard when she was young. She’s lived her whole life here and raised ten children on the island. But the settlement of Shishmaref is relatively new. Historically, the people in this region were seminomadic. They’d move based on the season, following resources abundant on the land and in the sea. This all changed in the early 1900s, when the Lutheran Church and the federal government built a church and a school on the island. The government pushed for all Alaska Native children to attend school, where many children were beaten for speaking their native language. This triggered a widespread loss of cultural identity, the impacts of which Shishmaref residents like Nora still feel today. Climate change is only one outside force that has created monumental shifts in daily life here.

Waves from the Chukchi Sea lap at a seawall built to protect Shishmaref. After a big storm consumed a chunk of the island in 2005, the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) built and expanded seawall protection around the island to guard it from future storms. But it offers only temporary safety—the sea wall, just like the coast, is gradually wearing away. In 2016, the village voted to relocate. It was the third time they’d made such a vote. But moving the whole village would cost about $180 million, according to a 2004 USACE report, and Shishmaref doesn’t have anything close to that kind of money. Some folks work in construction or at the local school, but according to the latest census information, about 40 percent of people on the island live below the poverty level.

Bone carver Harry Ningealook, 57, smokes a cigarette under a vent he’s built in his home. Under the vent, he can light up during harsh Arctic winters. The island is well known for intricate carvings on whale, walrus, and even mammoth bone. Harry comes from a long line of carvers. His great-grandfather was a carver, and Harry learned from his dad. He calls himself a “grandmaster carver.” Harry tells me he’s heard all the talk about President Trump building a border wall between the United States and Mexico. “He should build a wall around our island, make the money more worth it,” he says, laughing.

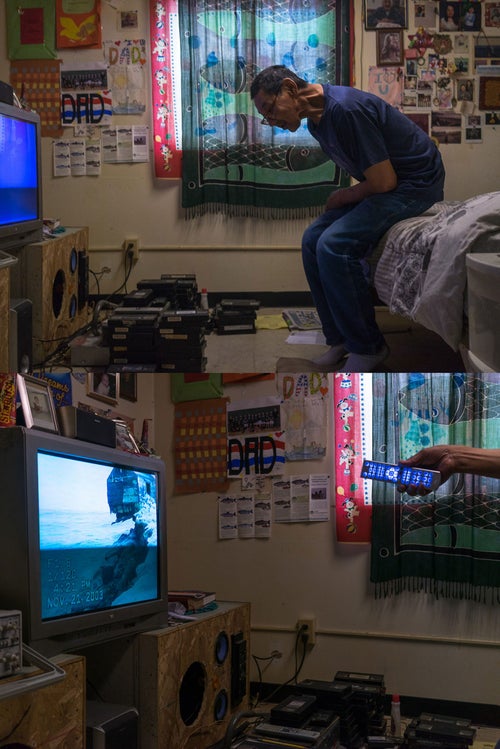

Dean Kuzuguk, 59, points to a house teetering on the edge of a storm-eaten cliff in a home movie from 2003. Dean’s a historian of sorts. He keeps tapes piled by the TV in his bedroom: old home movies, films about Shishmaref, anything featuring his community and the people he knows. Every time there’s a bad storm, Dean walks the island with his camcorder to document the damage.

Winfred Obruk, 78, takes Amy and me out to the beach behind his house. He says the beach used to extend way out beyond where it ends now. He gestures to the waves on the horizon. “We used to have a beach for playing baseball,” he says. “All this was like that.” Winfred points back to the beach on which we’re standing. “Sand.” Many people tell us of an old playground, drying racks for fish and seal meat, and other memories that the ocean has claimed over the years.

The people here are overwhelmingly young. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about half the population is under 25, and in a way, kids run this island. In the summer sun, they’re up late into the night, playing tag, riding bikes, and shooting hoops.

For these kids, climate change isn’t something abstract—it’s part of life. Shishmaref is just one of more than 30 Alaska Native coastal communities in imminent danger due to the effects of climate change. Residents here know the island won’t last forever. When relocation is discussed, it can mean two things: Everyone dispersing to larger communities, like Nome, Barrow, or Anchorage. Or it could mean keeping the residents of Shishmaref together, but in a new place. This option preserves the culture and community that helps people here thrive. However, it also costs money that people here don’t have, and the federal and state government aren’t willing to fork up.

Find out more about Shishmaref—and other ways in which the Arctic is changing—in season two of Threshold.