The First 4x4s to Traverse Greenland’s Ice Sheet

It took the team a year just to figure out the 3,212-mile Arctic route

What do you do next after becoming the first team to drive to the South Pole and across Antarctica? Head to the North Pole, obviously. There’s just one problem.

“The wild changes in ice conditions in that region have made a North Pole drive extremely unsafe and unpredictable,” says Scott Brady, publisher of Overland Journal and one of the leaders of Expeditions 7. Over the past decade, he and his team members have driven the same Toyota Land Cruisers across all seven continents, choosing the most challenging routes possible. But this time, the melting of our polar ice caps rendered their chosen objective seemingly impossible.

“There was a high probability of losing a vehicle into the ocean or failing to reach the North Pole,” Brady says.

“While I architected the initial seven-continent expedition, Greg Miller took the reins on this project and looked for the next frontier,” Brady says.

Miller, a Land Cruiser enthusiast and philanthropist who helped created E7, realized that no one had yet driven across Greenland from south to north, a journey that would require crossing thousands of miles of the island’s interior glaciers, risking falls into crevasses, run-ins with extreme weather, and the possibility of medical emergencies with no chance of outside help.

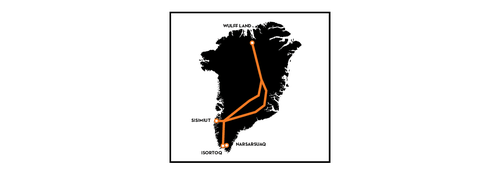

To map a viable route, the team used satellite imagery and glacial flow data to come up with the safest possible solution. It took a year of research to come up with the 3,212-mile route, which eventually took the seven-person team from Isortoq, on the south coast, to Wulff Land, at the northern terminus of the ice sheet, then back south to Kangerlussuaq, in western Greenland, and then along the Arctic Circle Trail to Sisimiut, on the coast.

Over the course of the 20-day trip, Brady, Miller, and the team encountered temperatures as low as minus 40 Fahrenheit and total whiteout conditions. They fell into crevasses, broke their trucks, and even had a fire break out in the expedition's main tent.

“It was intense,” Brady says. “Most maps of this region are simply labeled ‘unexplored.’”

Several incidents nearly caused the expedition to fail. Going into the trip, the team’s biggest worry was crossing the glaciers on the edges of the ice sheet as they climbed on and off the frozen mass that covers most of the island. “These glaciers are incredibly unstable and constantly changing,” Brady says. “It was like a minefield.” The team saw vehicles, people, and equipment fall into crevasses, but they were able to rescue them all successfully. They even managed to recover a truck that fell through ice on a frozen lake.

The biggest challenge came simply from the attrition of driving through harsh conditions. “The conditions were far worse than anticipated, the surface of the ice sheet deeply scarred by heavy winds that cause sastrugi,” Brady says. “These snow ridges are abusive to the vehicles and the occupants, slowing progress and making sleeping in the vehicles [while moving] nearly impossible. All of that tested the team to the limits and put completing the expedition at risk.”

“Originally, we had planned to camp almost every night, but the slow progress quickly changed the schedule,” Brady says. “This made an average day of moving more like 48 or 72 hours. We would make camp to prepare hot food and get a long sleep cycle. This was typically timed with repairs, service, and fueling (or a fuel drop). Every team member had responsibilities that could take up to ten hours in minus 30– to minus 40–degree temperatures. Several meals would be prepared in a large community tent as various jobs were completed. This would mean that 20 to 30 hours would be spent in a location, follow by 24 to 48 hours or more of driving. The most difficult part of this was getting sufficient rest, and the ruthless conditions made even the seemingly innocuous activities like defecating painful. Several of us experienced frostnip or frostbite. Even six weeks later, I still do not have all the feeling back in the tips of a few of my fingers.”

The team managed to break everything on the trucks. from axles to frames. Additionally, the truck that fell through the ice early in the trip developed ongoing mechanical issues. Just a few hours from reaching their northernmost objective, the team was exhausted and growing increasingly worried about wind-driven snow that was creating total whiteout conditions.

“It was looking bleak,” says Brady (pictured here). They were reevaluating the need to abandon their goal by the hour, and team members were beginning to fear for their lives. But just moments before reaching their point of no return, where they had to push on to that final northern fuel drop, the skies cleared. Brady and Miller agree that the biggest accomplishment of the 20-day journey was returning every person home safely.