The Piscivore’s Dilemma

The oceans are in serious trouble, creating a tough question for consumers: Should I eat wild fish, farmed fish, or no fish at all? The author, a longtime student of marine environments, dove into an amazing new world of ethical harvesters, renegade farmers, and problem-solving scientists. The result: your guide to sustainably enjoying nature's finest source of protein.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

I contemplated the simple sandwich on the plate in front of me: a beautiful slab of glistening rainbow trout, crisp lettuce, and a freshly baked French roll. The trout skin was lightly seared and seasoned. The pinkish meat was firm and toothsome. I genuflected briefly, then two-fisted the thing and took a big bite. A slightly smoky, sweet flavor gave my taste buds a sensation long denied. I chased it with a slug of Fort Point ale. Soon, both fish sandwich and beer were gone. I am a vegan, but I was untroubled. Eating the trout seemed like the right thing to do.Â

The journey to that sandwich began a few months earlier with a question from a friend who wants to eat sustainably: What fish can I eat? My response was the same one I have given for years: You should eat no fish at all.

I havenât always felt this way. I grew up on the East Coast, spent a lot of time on the Atlantic Ocean, and ate more than my share of salmon, tuna, crabs, scallops, and whatever other seafood was on offer. But a few years ago, as I began to write extensively about the relationship between humans and animals, especially the lives of marine mammals in captivity, my thinking changed. What we eat affects the health of the planet as much, if not more, than what kind of car we drive or where we set the thermostat. The more I learned, the more I came to believe that the single most powerful choice an individual can make is to stop eating animal protein. So, in 2010, I became a vegetarian. After about a year, realizing I could manage without cream in my coffee and eggs for breakfast, I took the next step and went vegan.

I didnât evangelize about it. I made my choice; others could make theirs. But I noticed that when I was asked about my reasons, there always seemed to be special interest in the question of fish, which even the vegetarian-inclined still want to eat. Setting aside my vegan concerns about fish welfareâlaugh if you like, but then go watch a beautiful, fighting-mad bluefin tuna being gaffed on YouTubeâanyone who has been paying attention knows a dispiriting truth: wild fish are being decimated by the worldâs increasingly teched-out, 4.7-million-vessel fishing fleet. that 90 percent of marine fish stocks are either fully exploited or overexploited. Meanwhile, fish farming, with its reputation for overcrowding and antibiotic-laced, fecal-polluting practices, doesnât sound like a very appealing solution. And there appears to be no shortage of crooks and liars, from fraudulent distributors to fact-twisting chefs and fishmongers, at just about every link in the distribution chain. , you canât even be sure your supermarket isnât stocking seafood caught by fish pirates in Indonesia, who kidnap and enslave impoverished Southeast Asians to work on their boats. The slaves work untenably long hours for little to no pay, are locked up at night, and are often beaten if they donât perform as told. Whereâs the argument for eating fish in all that?Â

But the questions kept coming, and I knew my personal position didnât provide realistic or helpful advice. Seafood is an indispensable source of protein and omega-3 fatty acidsâgood for the heart and brainâon a planet whose population will need a lot of protein as it swells toward a projected 9.3 billion people by 2050. My friends and family and most of the world will continue to eat fish, and despite all the seafood guides and journalism on the subject, people are more confused than everâabout whether to eat wild or farmed, about which fish are healthier, about the implications of fish consumption for the oceans.

âJust tell me what fish I can eat,â my mother pleaded. So I set out to produce a better answer, and what I learned surprised me. Not only might fish offer the best, and least ecologically damaging, solution to global food insecurity in a flesh-eating world, but some seafood is now produced so efficiently that even a vegan might be tempted to rethink his absolutist vows.Â

Wondering how to put it all into practice? We asked the experts and distilled their advice down to six rules of eating healthier, more sustainable seafood.

I. Consider the Source

The math is simple. Global demand for fish is at about 158 million metric tons annually (and growing), which is about twice the already worrisome 80 million metric tons we take from the oceans. Against that unrelenting pressure, it seems reckless to keep scarfing down wild fish.

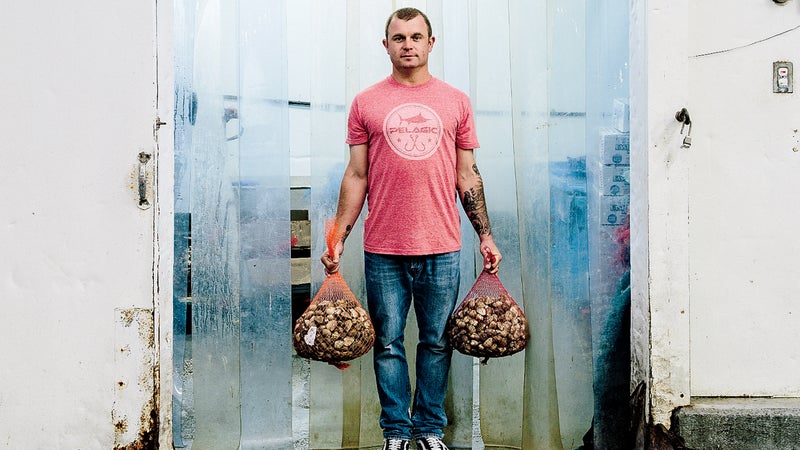

But Kenny Belov, a burly, high-energy 38-year-old who co-owns , a fish distributor on Fishermanâs Wharf in San Francisco, is quick to disabuse me of the idea that wild fish should be completely off the menu. Belov and his partner, Bill Foss, a cofounder of Netscape, caught my attention by lobbing grenades at their own industry in a probing about seafood sustainability (or lack thereof) a few years ago, and they have been outspoken advocates for rethinking our approach to eating fish ever since. Most days, Belov shows up at the TwoXSea warehouse at 3 A.M. to supervise the shipping of 1,500 to 2,000 pounds of seafood to top restaurants and stores in the Bay Area and a few other citiesâall of it sustainably caught. He is as obsessive and conservative as they come in his views about whether any fish population is healthy enough to be fished and whether the catch method damages other populations or the ocean ecosystem.Â

Atlantic cod? âItâs overfished and mostly caught by bottom trawling, which is like clear-cutting the seafloor,â Belov scoffs. âI wish we would leave Atlantic cod alone. They need more time to recover after what we did for so many generations.âÂ

Ahi tuna? âAlmost all of it is caught on pelagic longlines, which are 40-plus miles of floating line dangling a baited hook every three feet. Longlines catch everything else in the habitat.â Thatâs called bycatch, a somewhat bloodless term for a fishing method that indiscriminately hooks as many as 150,000 sea turtles annually, along with tens of thousands of seabirds, whales, sharks, dolphins, and porpoises.Â

The Alaskan pollock so often used for fish fingers? âCaught by fishing vessels that are 100 to 200 feet long,â Belov says. âTheir huge nets pull in lots of other species, like squid and salmon.â

So how is it that Belov has a warehouse full of sustainable wild fish? Because he scoured the West Coast fleet for fishermen who were tapping into healthy stocks the right way. Once he found them, he paid them a premium for their catch.

Belov walks me around TwoXSeaâs facilities. On the day I visit, heâs got Coho salmonâbeautiful, powerful, silvery fishâthat were caught by the High Hope, out of Sitka, Alaska, using a method called trolling, in which a few lines are dropped behind a boat and pulled in one by one, reducing the risk of bycatch. Heâs also got black cod, targeted with baited lines set by the Eagle III in Coos Bay, Oregon, and night smelt from Eureka, California. It was harvested by a fisherman named Dude Gifford, who dips a net stretched across an A-frame of poles into the surf. âWe donât sell anything that doesnât come directly from a fisherman,â Belov says.Â

The real problem, he believes, is not that sustainable fish stocks arenât out there. Itâs that a lot of unsustainable fish is passed off as OK. Belov and Foss are also partners in a Sausalito restaurant called Fish, which Foss opened in 2004, promising customers that everything on its menu could be eaten with a clear conscience. They launched TwoXSea five years later because they got fed up with all the dishonesty they encountered trying to supply fish for Fish. âThere is so much seafood fraud going on when it comes to labeling species, its origin, and the captain and vessel,â Belov says. He tells me about the time he went looking for scallops that hadnât been caught by dredging, a process that tears up the seabed. He met with two distributors from New York City and explained that he would need traceability, vessel names, and documentation to confirm the catch method. Their glib responses made it clear that the information would be meaningless. âWe have a long list of boat names,â they told Belov. âJust pick any one you want.â

Belov is not being paranoid. A , a nonprofit that campaigns to protect and restore the worldâs oceans, concluded that 33 percent of fish in the United States is fraudulently labeled to increase profits. (There is now a presidential task force trying to address the problem.) To emphasize the point, Belov walks me outside onto the pier. He gestures toward two swordfish-longlining vessels that are tied up alongside another fish distributorâs warehouse. âSee those boats?â he says. âBecause they unloaded their swordfish here, it can be labeled PRODUCT OF CALIFORNIA, which means it will be sold to diners as local or San Francisco swordfish, even though it was caught 1,500 miles away in the middle of the Pacific.â He says restaurants will probably describe the swordfish as âline caught,â which sounds positively artisanal.

But both Belov and Foss believe that things are getting better and that the success of TwoXSea is in large part due to a younger generation of chefs who are making decisions based on an ethical rather than a financial stance. âPeople are much more aware of what is going on with dishonesty in seafood and all the fraud,â Belov says. âBut I still think we have a tremendous way to go,â adding that when it comes to seafood sustainability, personal choices matter.

By the time Belov is done with me, I have a few new beliefs. One is that you can eat some wild seafood without trashing the oceansâwild-caught Alaskan salmon, for example, is a well-managed fishery. Another is that, in a perfect world, we would all know the name of the fisherman reeling in our fish, but thatâs not the reality for most of us. There is so much complexity in catch methods, fishery management, and the supply chain that even a conscientious seafood lover might as well throw a dart at the menu. Luckily, thereâs an app for that.Â

II. Red Light, Green Light

The , two hours south of San Francisco, is housed in an old sardine cannery, and one of its feature attractions is a 335,000-gallon viewing tank that contains a forest of California kelp. Jennifer Dianto Kemmerly, 42, the director of the aquariumâs and an environmental scientist, sits down at a table in the cafeteria, her hair still damp from an early-morning dive into the kelp. There are a lot of seafood standards out there, but Seafood Watchâs are arguably the most independent, comprehensive, and rigorous, and it has taken a tough, truth-telling approach to assessing fisheriesâ sustainability. âWhen we started red-rating fisheries in our own backyard, that was a really bold move,â Kemmerly says. âBut after ten years lots of fish came back, and the message was heard by fisheries up and down the coast.â

Seafood Watch was launched in 1999, after aquarium visitors started walking off with cafeteria display cards listing a few which-fish-to-eat recommendations. Seeing an opportunity, the aquarium put together a program to produce detailed, science-based evaluations of specific fisheries to publish on its website and . Fish from well-managed, abundant populationsâcaught in a way that caused little harm to other species or habitatâgot a green Best Choice designation. Fish that were OK to buy but were harvested in a way that caused Seafood Watch some concern, garnered a yellow Proceed with Caution tag, since changed to Good Alternative. Fish from a badly managed, overfished, or destructive fishery got called out with a red Avoid label.Â

Today, Seafood Watch has more than 2,000 unique recommendations, on both wild and farmed seafood, updated at least every three years. Of those, 22 percent are Best Choice, 38 percent are Good Alternative, and 40 percent are Avoid. More than 1,000 North American companies use this information in their buying decisions, and more than a million users have downloaded the app.Â

Seafood Watch data affirms that, in well-managed U.S. fisheries, sustainable wild fish is available. The programâs scientists recently assessed 129 species, which account for three million metric tons of catch annually. Of that haul, more than half a million tons, or 19 percent, are rated Best Choice. And just 2 percent are Avoid, which leaves 79 percent in the yellow Good Alternative limboâa rating that worries some seafood advocates because it sounds too much like a buy recommendation. I mention to Kemmerly that eating a lot of yellow-rated seafood doesnât seem very sustainable. âIt isnât,â she says. âBut if weâd set the bar that you could only buy green, I donât think this market-based-incentive movement would be pragmatic.âÂ

Still, the truly conscientious seafood eater should aim to buy Best Choice, taking a precautionary approach and reducing our impact on fragile and complex ocean ecosystems. Plus, the more sustainable the rating, the less likely you are to eat seafood caught by fish pirates. âIf there is a known IUUââillegal, unreported, unregulatedââissue, then that will result in a red Avoid rating,â says Kemmerly. Though she cautions, âUnless there is full traceability from boat to plate, one canât be sure if the product comes from a vessel that engaged in IUU activity.â

Eating in the green zone takes some dedication. That is, when you can find it and afford itâwild-caught Alaskan salmon can cost upwards of $15 a pound. And even with the app, youâll have to ask a lot of questions.

Take albacore tuna. If it was caught by trolling or with a pole, in the North Atlantic or Pacific, Seafood Watch rates it a Best Choice. But if it was caught anywhere in the world on a longlineâexcept off Hawaii and in the U.S. Atlantic, which have strict bycatch limitsâit gets a red Avoid rating. Will the person selling you the fish know how it was caught and where, and can you be sure that personâs information is accurate?

Clear labeling at supermarkets and restaurants would make life a lot easier for consumers, and that is starting to happen. Seafood Watch and the , a New Yorkâbased ocean-conservation nonprofit run by marine ecologist Carl Safina, have partnered with Whole Foods on labeling, which has sold no red-listed wild seafood since 2012. Safeway, Target, and other supermarkets are working to implement similar changes. Meanwhile, 145 restaurants listed on the Seafood Watch site have also gone no-red.Â

What about when thereâs no labeling at all, which is the case in most restaurants and stores? Use the app and ask questions about catch method and location. âIt shows businesses that they have to stay on it,â Kemmerly says.Â

After she takes off for a meeting, I check out the aquariumâs cafeteria menu. The fish tostadas, at $15, are made using albacore tuna. Troll- or pole-caught in the Pacific, and not by longline, I assume, after glancing at my app. But Iâd have to ask.

III. Modern Farmer

As diligent as you might be with the Seafood Watch app, there isnât enough sustainable wild fish to feed the growing world. To fill the gap, many suppliers have turned to aquaculture, which has exploded from producing 1.6 million metric tons in 1960 to 66.6 million metric tons in 2012 and now provides about half of all the seafood we consume.Â

Farmed fish has confused consumers for years. Is it healthy? Bad for the environment? âLike any farming, aquaculture can be done well or it can be one of the most destructive things,â says Safina, who has fought for the oceans for more than two decades. âParticulars matter. There is sustainable aquaculture, and there are also fish farms that have wrecked coastal zones and mangroves and done bad things to poor people.â

Nearly 60 percent of fish farming takes place inland, in ponds and closed aquaculture systems, and produces finfish like tilapia, catfish, and carp, as well as shrimp. Pond farming conjures up images of overcrowded, feces-filled pools that require chemicals and antibiotics. But these days, most U.S. inland farming is done in line with good, healthy standards. U.S.âfarmed catfish, salmon, and shrimp are all Seafood Watch Best Choices. Tilapia is also popular, and if itâs farmed in Canada, the U.S., or Ecuador, it too rates a Best Choice. Farmed tilapia and carp from China and other parts of Asia often get dinged to yellow for questionable chemical use and waste-management practices.Â

Itâs the seafood raised in marine environmentsâespecially salmon and shrimpâthat has given aquaculture its controversial reputation. Waste, chemicals, antibiotics, and unused feed pollute nearby waters, farmed-fish escapees from these net pens threaten to spread disease and alien DNA to wild populations, and sensitive coastal environments become industrialized.

Marine fish farming also has a resource-use problem. Itâs known as the fish-in, fish-out (or FIFO) ratio, and itâs an important measure of sustainability. Consider farmed salmon. According to Seafood Watch, it can take three pounds of smaller forage fish, like anchovies, menhaden, and sardines, to create the feed needed to produce a pound of salmon; even the most efficient farms have a ratio of 1.5:1. Thatâs not a particularly sustainable way to produce fish. For all these reasons, until recently Seafood Watch slapped most finfish farmed in marine environments with a red Avoid rating.

Kemmerly, however, believes that weâre on the verge of a paradigm shift, thanks to advances in aquaculture over the past decade or so. âIt can be done responsibly,â she says.

To see what the future could look like, I seek out Josh Goldman, CEO of a company called . I find him, bespectacled and busy, in a cavernous two-acre warehouse complex in Turners Falls, Massachusetts, on the Connecticut River, which serves as company headquarters. Inside, itâs warm and humid, and the air is redolent with the sharp smell of a million fish, the sweet aroma of pellet feed, and the earthy fug of damp concrete.

Goldman walks me around, past massive tanks enmeshed in a complex web of -filters and industrial piping, until we stop at a Jacuzzi-size tank teeming with beefy-looking fish. Theyâre called barramundi, which is Aboriginal for âlarge-scaled fish.â In the wild, they can be found from northern Australia up through Southeast Asia and beyond, all the way to the coastal waters of India and Sri Lanka. These fish, though, did all their growing in Goldmanâs tanks, which collectively contain 2.5 million gallons of water. Over 300 days, they were transformed from tadpole-size hatchlings, weighing just one-third of a gram, into meaty fish weighing one to two pounds.Â

Goldman has been experimenting with aquaculture since he first got hooked on the natural sciences at Massachusettsâs Hampshire College in the early 1980s. He thinks weâre in a transition from wild fish to farmed fish that is similar to the transition 13,000 years ago from hunting meat to domesticating it. âBut we have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes,â he says.Â

To Goldman, the key is domesticating the right fish. After years of trying to improve on farming methods for popular species like striped bass, Goldman created a matrix of qualities that would make for a better farmed fish and, in 2000, started prospecting the world to find it. He ticks off some of the reasons barramundi fit his better-fish matrix: they have the high fecundity of a marine fish (large females can produce up to 40 million eggs in one season); they travel up rivers to forage, which means they are tough and adaptable; and they eat a flexible diet that includes plants. By experimenting with feed compositions over the growth cycle, Goldman managed to drive the FIFO at Turners Falls down to an impressive 0.98:1, meaning that it takes less than a pound of wild fish to produce a pound of barramundi. Seafood Watch approved, rating Goldmanâs indoor barramundi, which has a sweet, buttery flavor and is packed with omega-3âs, a Best Choice.

Goldmanâs next challenge was to take barramundi out of the tanks and grow it to scale in a marine net-pen farm. âPeople were looking at aquaculture in coastal zones as an environmentally harmful activity,â he says. âI wanted to right that wrong.â

He went prospecting again and found the location he needed in Van Phong Bay, on Vietnamâs southeast coast. Australis Aquaculture Vietnam started production in 2010. Today it turns out some 2,000 tons of barramundi a yearâmore than three times the output at Turners Falls, at roughly half the costâand has permits to scale up to 10,000 tons annually. Its frozen fillets are shipped to more than 4,000 stores across North America and cost a reasonable $9 a pound at my local Whole Foods. Careful net-pen siting and low fish densities reduce pollution and the threat of disease. Antibiotics are used sparingly and only as needed, and escapees are rare and not much of a concern, since local barramundi were used as the brood stock in Australisâs hatchery. Last year, after careful inspection, Seafood Watch gave Australis Aquaculture Vietnamâs barramundi the first green Best Choice rating ever granted to a marine net-pen fish.Â

âI donât think there is any question that barramundi can be a real player in global supply,â says Goldman, who already has his eye on another fish that looks farm friendly, though he wonât say what it is yet.Â

Meanwhile, for the consumer, itâs now much easier to find farmed Best Choice options. Of the 176 farmed recommendations on Seafood Watch, 52 percent are Best Choice, 40 percent Avoid. From inland farms, there is rainbow trout, Arctic char, and salmon. Then thereâs marine net-pen fish like Goldmanâs barramundi and New Zealandâs newly green-rated Chinook salmon. If thatâs hard to find, Best Choice farmed tilapia and catfish, while not high in -omega-3âs, are still a healthy and affordable protein.Â

IV. Vegan Fish

After visiting Turners Falls, I start imagining a world increasingly fed by innovative aquaculture. Itâs a hopeful vision, except for one glitchâthe FIFO problem. Most of aquaculture relies on forage fish to provide fish meal for protein and fish oil for omega-3 fats, which they get from eating microalgae and phytoplankton in the ocean. But global forage-fish harvests have maxed out at 20 million to 25 million metric tons, a volume that some experts worry is too high. The industry has been doing a better job scavenging from fish-processing waste, but there are still a limited number of forage fish that can be taken from the sea, which is a serious impediment to sustainable aquaculture growth.

This problem inspired Bill Foss, Belovâs partner at Fish and TwoXSea, to ask fish farmers a question that could change everything: Why do you need to have fish in your feed?

âItâs been a well-known fact that the amount of fish needed to feed a fish is a pretty asinine way to produce a fish,â says Foss, sitting in a coffee shop in Petaluma, California. Foss, who is 50 and has little patience for the shortsightedness of the human race, tells me that about five years into supplying fish for his restaurant, Belov found out that their farmed Best Choice tilapia and troutâboth of which can feed on plantsâwerenât vegetarian. Neither wanted to serve fish that consumed overstressed wild forage-fish stocks. Besides, the cost of fish meal and fish oil has more than tripled over a decade.

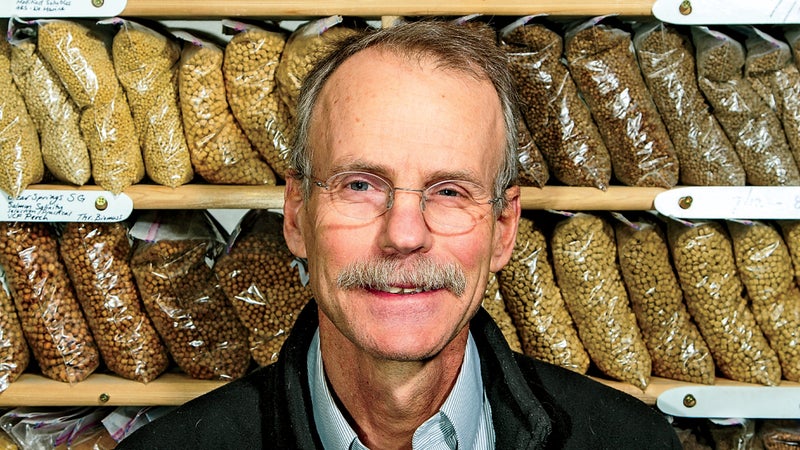

To formulate a novel fish-free feed, Foss turned to a freethinking scientist: Rick Barrows, at the USDAâs Agricultural Research Service in Bozeman, Montana. Barrows is a slim, deliberate man, with wire-rim glasses and a wide mustache. His official title is research physiologist. Thatâs a sterile description for someone who has been on a decades-long quest to find the holy grail of aquaculture: replacing fish meal and fish oil in the feeds that sustain the industry. His research mainly takes place inside a lab tucked into the foothills outside Bozeman, where 320 holding tanks are arrayed in neat clusters, most containing small populations of rainbow trout. When Barrows shows me in, two assistants are netting, weighing, and grading the growth of some troutââthe white rats of aquaculture,â Barrows jokesâthat are eating a pistachio-based feed made from deformed nuts rejected for human consumption.

Barrows has looked for an alternative to fish-based meal in everything from corn and soy to pistachios and peas. Heâs even experimenting with black soldier fly larvae. âIt was fairly easy to come up with a variety of new protein sources,â he says.Â

Last year, Barrows made more than 150 feeds for 22 fish species, and his research has proved that at least eight popular fish-farm species, including trout, salmon, and sea bass, can grow just as fast, or faster, on fish-meal-free feed. âIf we can do it with those eight, we can do it with any fish,â he says.Â

Replacing fish oil, the key to providing the two omega-3âsâDHA and EPAâthat are associated with good brain and heart health, was more difficult, Barrows says. We head out to look at the feed mill, where Barrows and his team homebrew their experimental feeds. They start with a mash of whatever ingredients theyâre using and then run it through a massive twin-screw extruder, a machine used to make everything from dog food to Froot Loops. Today itâs spitting out small orange pellets, which drop into a large plastic garbage can. I suggest to Barrows that people should skip the fish and just consume the pellets directly. He grins. âSure, you could eat it instead of cereal. Foss gave it a try.âÂ

Foss and Barrows eventually solved the omega-3 problem by adding an algae-based DHA supplement, often used in baby formula, to the vegan feed, which also contains pea protein and flax oil (and love, Belov jokes). Since 2010, they have tried it out on successive generations of rainbow trout at a farm Foss and Belov purchased in the Sierra Nevada near Susanville, California, run by David McFarland. The results have been interesting. The trout show a good DHA profile and also seem to be converting at least some of the DHA into EPA. âSo DHA is all we needâthe trout does the rest. Kinda cool, huh?â says Foss. âPlus, the algal DHA has none of the mercury or PCBs that come from forage fish, so weâre ahead in the health game.âÂ

Unfortunately, the DHA supplement is expensive, which means that the vegan feed is priceyâ$1.50 a pound rather than the 80 cents a pound for standard forage-fish-based feeds. That adds about 15 percent to the cost of the trout. If the costs of fish meal and fish oil continue to climb, the price differential will shrink or disappear. More demand and scaled-up production of the vegan feed would also bring the cost down. âThe biggest thing holding us back is that someone like Whole Foods hasnât said, âWe want a million pounds of what youâve got,âââ Foss grumbles.

Australisâs Goldman, among others, is also experimenting with alternate plant-oil sources that might produce omega-3âs in fish. Until more farmed fish fed a vegan diet are widely available, try to add in FIFO-light options, like tilapia and catfish, to your menu. Thereâs also another solution.

V. The Seafood Chain

Itâs tempting to think that as long as something is a green Best Choice, you can eat as much as you want. But Barton Seaver, a former chef who is now the director of the at Harvardâs T. H. Chan School of Public Health, would like seafood lovers to be conscious of more than a rating. Seaver, 36 and lanky, is a thoughtful presence who carries the slightly haunted air of a man who is wearied by all he knows. To Seaver, smaller portions and variety are key elements of sustainability. âWhatâs important is eating less seafood more often,â he says, noting that we get more nutrients than we need when we chow down on a large slab of fish.Â

Seaver spent his summers as a child fishing and crabbing on the Chesapeake Bayâs Patuxent River. In 2007, when he was 27, he opened Hook, a popular seafood restaurant in Washington, D.C. He got interested in sustainability after he called up a seafood supplier to place his first order. âSend me bluefish, crab, oysters, rockfish,â he said, eager to feature all the Chesapeake bounty he had loved as a boy. âKid, what are you talking about?â the supplier responded. âWe ate all those.â

âI realized that natural selection in our world is firmly holding a fork,â Seaver says.Â

I met with Seaver in Portland, Maine, in January, to see his friend Gary Morettiâs Casco Bay mussel farm. Moretti, a 63-year-old with the cheerful spirit of a man who loves being on the water, co-owns with his son, Matt. As he gets ready to back his converted lobster boat away from the wharf, a seal pops its head up. âHey, Loretta, get out of the way,â he calls. âDonât worry, Iâll give you a fish later.â

Within minutes weâre chugging toward Clapboard Island, where Bangs Island keeps four mussel raftsâ40-by-40-foot steel frames dangling 400 fuzzy ropes to a depth of 30 to 40 feet, for mussels to adhere to. In the relative warmth of the boatâs wheelhouse, Moretti explains that siting a mussel farm is all about thinking like a mussel. You want plenty of phytoplankton, minimal sediment, and nice current-driven water flow that is uncontaminated by golf-course or industrial runoff. âBut this is Casco Bay. Here you can pretty much grow mussels anywhere,â he says of the beautiful seascape around us.

We pull alongside a mussel raft, and Moretti and Seaver hop onto the ice-slicked girders. They tug up some lines to show me the thick clusters of blue-black bivalves growing under the raft. It occurs to me that I am looking at the ideal farmed protein. It requires no feed beyond the nutrients in the water, so it has a perfect FIFOâno fish in for lots of shellfish out. It filter-feeds, improving water quality instead of polluting it. There are a multitude of coastal zones around the globe where mussels can grow in abundance. And while they donât pack the omega-3 wallop that salmon does, they do deliver a shotâthree servings a week gets you to the recommended minimum. Another bonus: being low on the food chain, mussels have little mercury, more than 30 times less than larger predator species like swordfish and tuna.

âThe benefit of mussels is you canât be greedy and wolf them down,â says Seaver. âThere is an elegance and mindfulness to eating them.â

If ever there was an animal protein that a vegan could adopt, the mussel is it, I decide. Because of their rudimentary nervous system, they likely feel no pain and would give me some DHA and EPA omega-3âs, which are mostly absent in the vegan diet. (Flaxseed, popular with vegans, provides a different omega-3.) Farmed mussels are a Seafood Watch Best Choice, but I start to think of them as a Super Green Choice.Â

I realize that an interesting thing happens when you approach seafood with sustainability and health in mind: you end up eating a diverse diet that pushes you lower down the food chain and away from the rut of salmon, shrimp, and tuna, the most commonly eaten seafood in the U.S. The healthiest, most sustainable seafood thatâs also high in omega-3âs and low in mercury? Wild Pacific sardines, a Best Choice. Other green-listed options that have decent omega-3âs and low mercury: U.S.âfarmed striped bass, U.S.âfarmed rainbow trout, farmed Arctic char, Australisâs barramundi, and wild or farmed mussels. Wild or farmed oysters, farmed scallops, farmed tilapia and catfishâuse your Seafood Watch app to find the Best Choice for theseâare also highly sustainable and provide good protein, some omega-3âs, and little mercury. For an occasional treat and a massive shot of omega-3âs, have some Best Choice wild Alaskan salmon every once in a while. Thatâs a pretty green way to get all the protein and omega-3âs you need without going too heavy on the FIFO scale.Â

VI. Navigating the Marketplace

When I get home, I make a run to Costco to shop at the seafood counter with fresh eyes. It isnât easy. I see a few Marine Stewardship Council CERTIFIED SUSTAINABLE SEAFOOD stickers. MSC is a nonprofit that certifies fisheries that meet its sustainability and traceability standards. Though the standard has critics, Seafood Watch recommends most MSC-certified fisheries and says that they are equivalent to at least a yellow Good Alternative. Still, most of Costcoâs seafood is unlabeled. So itâs me and the Seafood Watch app.

I work my way down the cooler. Farmed salmon from Chileâred, with an unappealing label that says âcolor added.â (Some farmed salmon are fed the carotenoid astaxanthin to give their flesh the orange color theyâd normally get from eating shrimp and krill in the wild.) MSC-certified wild Atlantic codâyellow. Ahi tuna from the Marshall Islands in the western Pacificâthereâs no information on how it was caught, and the Costco employee stocking the cooler doesnât know, so I worry it was a longline and would rate red. I find some tilapia farmed in Honduras, but Seafood Watch is still in the process of rating it. In the frozen section, itâs more of the same. Most everything seems to fall into that yellow, not-egregious-but-not-really-OK category. I call Belov for guidance. âItâs so complicated, and there are too many standards,â he says sympathetically. âWe have a long way to go, but all we can do is keep pushing and asking questions.â

Later, when I check in with Bill Mardon, Costcoâs assistant general merchandising manager in fresh seafood and poultry, he explains that Costco doesnât sell 12 of the most overfished species and is working toward having more of its seafood supply meet MSC or Aquaculture Stewardship Council standards. (ASC was created by the World Wildlife Fund and the Sustainable Trade Initiative; its certified catfish, shellfish, and shrimp equate to at least a Seafood Watch Good Alternative.) âOne hundred percent of our tilapia is ASC certified, and this year we are getting going on salmon and shrimp,â Mardon says. âCall me in two, three, or four years, and I hope we will be at 80, 90, or 100 percent.â

A few days later I hit up my local Whole Foods, and the experience is a lot simpler. Whole Foods sells MSC Certified Sustainable wild fish and puts Seafood Watch labeling on any wild fish that MSC hasnât certified yet. A graphic atop the counter explains the color coding and tells shoppers that if itâs red, âWe donât sell it!â âThe whole point of having these high standards is that any choice you make is a responsible one,â says Carrie Brownstein, the global seafood quality-standards coordinator for Whole Foods and a former research coordinator at the Safina Center.

I see a lot of choice: croaker, halibut, cod, and hake. Most of the Seafood Watch labels are yellowâwhich reflects the state of wild fisheriesâbut I spot some green-rated Best Choice wild Spanish mackerel for $9 a pound. (Brownstein told me that whatâs available varies seasonally and regionally, which affects how much green-rated wild fish you might find at any given time.) Thereâs also a lot of farmed seafoodâtilapia, catfish, shrimp, Arctic char. Whole Foods has certified it with its own Responsibly Farmed logo, which requires aquaculturists to meet a strict standard on pollution, chemical and antibiotic use, and other criteria. Most of it, as far as I can tell, would earn a green, and I can see a Best Choice menu here that my mother could happily live on. Thereâs a good supply of oysters, mussels, and clams, both farmed and wild, and the farmed tilapia and catfish. She might also be tempted by Spanish mackerel. In the frozen section, I find some of Australisâs Vietnam barramundi fillets.

âAnything you buy regularly, Iâd stay in the green,â says Safina, who tries to eat only seafood that he catches himself. âBut if itâs something you splurge on once a summer, then yellow is probably OK.â Still, he adds: âIf you really want to be conscientious about seafood, you should eat rice and beans.â

I agree. While Iâm encouraged by the promise of better fisheries management and aquaculture innovation, I still donât intend to eat fish, for the same reasons I stopped in the first place. I believe in author Wendell Berryâs observation that âhow we eat determines, to a considerable extent, how the world is used,â and I want to use the world less. Fish raised in tanks, no matter how well cared for or sustainable, are inevitably the human processing of living things. Even TwoXSeaâs delicious vegan rainbow trout, which spend their lives high in the Sierra Nevada in perhaps the most beautiful farming environment on the planet, tug at my conscience. To see them idling in concrete raceways instead of chasing an insect hatch is a reminder that farmed life is a faint facsimile of life in the wild. But I will maintain my exemption for mussels, which in my opinion are an ethically defensible animal protein.Â

Regardless, a sustainable approach to seafood has a lot to offer. Andy Sharpless, the CEO of Oceana and the coauthor of a book about fish called , says that if we stopped overfishing and gave spawning stocks a chance to rebuild, most fisheries would fully recover within ten years and allow sustainable harvests that are 20 to 40 percent higher than the current global catch. âA well-managed global ocean could provide the equivalent of a healthy seafood meal for a billion people every day forever,â he says.

Meanwhile, itâs worth asking: How many apps rate other kinds of meat according to its environmental footprint? âIf we are scared away from buying farmed salmon because it is red-listed, what do we do instead? We go buy ground beef,â Seaver points out. âIf you look at the environmental factors of protein by category, often those other proteinsâbeef, pork, chickenâhave a larger impact than even the worst of the seafood products.â

So with apologies to Michael Pollan, Iâd recommend this for conscientious nonvegans: Eat a lot less meat and a lot more sustainable seafood, wild when you can verify it, and lower on the food chain, but mostly farmed, particularly mussels, clams, and oysters.Â

On the way back from Clapboard Island with Seaver and Moretti, stamping our feet in the wheelhouse to stay warm, I fantasized out loud about a universal food-labeling system that would rate everything according to its environmental impact and health benefits. Of course, Iâd like an animal-welfare rating, too, but I donât want to get carried away. Moretti told me about his fantasy: converting used offshore drilling platforms into massive mussel farms to help feed a growing world population. âIn my dream, Bill Gates or Warren Buffett calls me up and says: âHey, Gary, I really think we should do that oil-rig-mussel thing. Hereâs $100 million.ââ We smiled at the improbabilitiesâand the potential.   Â

Correspondent Tim Zimmermann ()Â was an associate producer of the documentary Blackfish. He wrote about zoos in March.