EXERCISE ZEALOTS, spa lovers, organic-food junkies, and luxury seekers: Welcome home. Canyon Ranch, the Tucson, Arizona–based wellness resort known for seducing people into optimal health, is now spinning its popular get-fit vacation philosophy into the first-ever ür-healthy-living residential complex aimed at boomers with bling. Opening next spring in Miami Beach, Florida, Canyon Ranch Living will be the oceanfront health club you never have to leave—nor will you want to. The six-acre property will include 467 condominiums decked out with picture windows and private balconies off the ultraluxe nature-inspired rooms. “Our guests kept saying they loved their Canyon Ranch vacation but that when they went home, they wanted the same access to wellness,” says Kevin Kelly, Canyon Ranch Living’s CEO. Say no more. Wellness devotees can pick up a 720- to 3,000-square-foot CRL condo for $450,000 to $3 million. Of course, the price includes access to a 60,000-square-foot rooftop fitness center tricked out with a two-and-a-half-story climbing wall, private workout rooms, a spa, and the latest European whirlpools and other “wet-room” technology. When not working out or getting a spa treatment, residents and their guests can chill on 750 feet of white-sand beach frontage and refuel at CRL’s café, which serves up fresh, chemical-free seafood, meats, and vegetables, dished out in perfectly balanced portions. Just visiting to check out property? Crash at CRL’s David Rockwell–designed hotel. 888-987-9876,

Plate Tectonics

Dig into the world of delicious, nutritious eats, so you can feel great, play hard, live longer—and go for the gusto. for the full ���ϳԹ��� overview.Fast Food Goes Fresh: Chipotle Mexican Grill

STEVE ELLIS IS ON A MISSION. He’s determined to feed you vegetarian-fed, antibiotic-free chicken, real lime juice, organic pinto beans, unprocessed pork, and other sustainable and whole foods. And he wants those ingredients to be as all-natural as possible. If you’re picturing a back-alley boho café in Berkeley, try again. Ells is the visionary behind, and CEO of, Chipotle Mexican Grill, arguably the first fast-food franchise to make fresh and natural a priority and still turn a profit. Inspired by taquerias he frequented in San Francisco’s Mission District while a chef at the famed restaurant Stars, Ells—who graduated from the Culinary Institute of America, in Hyde Park, New York—created Chipotle’s business model around the idea of wrapping nutritious meals in a tortilla and selling them cheap and quick. (A typical burrito is ready in less than one minute and sets you back about $6.) His original 20-seat shop, on East Evans Avenue, in Denver, has mushroomed into an 11,000-person, $480 million company with more than 400 restaurants in 22 states—and two new ones opening each week. Chipotle’s has been so successful, in fact, that it was purchased by McDonald’s seven years ago. While some might think that’s dealing with the devil when it comes to fresh fare, Ells assures that it isn’t. “Not once has McDonald’s asked us to buy cheaper ingredients,” says Ells. “As long as we’re successful, we’ll have full autonomy.”

Sugar Busting Is Back

IF 2004’s AXIS OF DIETARY EVIL rotated around bread, well, hold on to your bacon, dear consumer, because the packaged-foods industry is about to pull a bait-and-switch down at your local Piggly Wiggly. In the coming months, watch for the omnipresent low carb labels to quietly recede from store shelves as that fad finally, blessedly collapses under a mountain of celery sticks. In its place, expect the makers of everything from cereals to juice to pancake syrup to hit sedentary Americans with a new fast-fix stamp: low sugar. Wait, is this 1981? With that year’s FDA approval of aspartame, the whole country went on a sugar-free high that lasted until the fat-gram-counting craze of the nineties. But things will be different this time around, according to Bob Goldin, vice president of the Chicago-based food-biz consultancy Technomic. “There’s a new concern about the staggering amount of sugar we’re consuming, which has continued to escalate over the past 20 years,” he says. Low-carb mania has evolved to identify sugar—a carb—as the real devil in the details. Its alarming abundance, hidden in everything from soda to teriyaki sauce, has prompted a slew of new products that either cut that sugar content way down or swap it for a lower-impact substitute, like Splenda. Mind the sugar intake, but remember: Exercise works wonders, too.

Queen of Celeb Cuisine: Akasha Richmond

Akasha Richmond

Serving Tinseltown since 1980: Chef Akasha Richmond

Serving Tinseltown since 1980: Chef Akasha RichmondWHEN A FAD SEIZES the American imagination, chances are it was born in Hollywood. And if eating well is now a national habit, give props to Akasha Richmond, healthy-food chef to the stars. When the native of Hollywood, Florida, landed on the West Coast in the early eighties, the glitterati were just adding words like cholesterol and organic to their lexicon. Richmond, working at the now defunct Golden Temple, in L.A., started serving up soy-based main courses and sugar-free desserts that convinced the Tinseltown vanguard that vegetarian food could be savory. When she left the restaurant in 1984, diners wept in their tempeh, but they soon clamored for her private service. She went on to become a personal chef to Carrie Fisher, Barbra Streisand, and others, and penned her first book, The Art of Tofu, in 1997. The beautiful people still line up for what Richmond modestly calls her “clean, organic, artisan, sustainable, and authentic” dishes, which rely on simple, fresh ingredients like organic ginger-honey syrup from a friend’s farm in Costa Rica and the best olive oil from Tuscany. The result: such wonders as crispy shiitake pot stickers and Billy Bob Thornton’s favorite, carrot cake made with spelt flour. One of Richmond’s latest creations was an African-style high tea for a benefit hosted by Pierce Brosnan. It was equal parts brilliant execution and kitchen confidential—which, along with her cooking, is what gives her staying power in this fickle city. “I don’t gossip to Star Magazine about my clients,” Richmond says. “Hollywood is too small a town.”

Al Fresco Extreme

Jim Denevan

Jim Denevan and assistant events coordinator Natalie Mock

Jim Denevan and assistant events coordinator Natalie MockChanning Daughters Winery

The evening’s selections, from Channing Daughters Winery

The evening’s selections, from Channing Daughters Winery“WE WANT TO RATE our dinners like whitewater,” says Santa Cruz, California–based Jim Denevan, perhaps the nation’s leading extreme-dining impresario. “Class I, Class II, Class III.” No, this isn’t about snacking on spiders at the Explorers Club. Picture wild boar pit-roasted on a mountaintop or freshly caught salmon savored in a remote sea cave by candlelight. Or, in a dinner planned this spring for Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, a multicourse, ultra-gourmet, white-tablecloth “intertidal dinner” staged on tidal flats in the brief window before Puget Sound floods the party. Lifelong surfer Denevan, 43, is the executive chef of Santa Cruz’s Gabriella Café. He is also the culinary brains and six-foot-four brawn behind Outstanding in the Field, a series of outdoor dinners now in its sixth year. Pairing fine wine and cuisine with rustic environs is not in itself novel: Rafting outfits, for example, routinely pamper clients with prime rib. But Denevan—with help from celebrity chefs like Dan Barber, of New York’s Blue Hill restaurant (see “,”), and Paul Kahan, of Chicago’s Blackbird—is proving that al fresco dining can be high adventure in its own right. To that end, a hundred guests recently forked over $130 each to follow Denevan on an intentionally confusing hike in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Once they were good and lost, Denevan led them to a well-laid table at the top-secret wild-mushroom site of local forager David Chambers. There, beneath the oaks and Monterey pines, Denevan served porcinis and chanterelles with local wild venison, wild sorrel greens brought out by the first rain, and mussels gathered by hand then poached in water first used to boil wild thistles. “So many restaurant menus try to tell a story these days,” he says. “They try to conjure the whole sensuous experience of a farm or where the beef was raised or where the fish was caught. We bring that story to life, so you can live it while you eat it.”

Slow Mojo: Organic Ingredients

Eat your broccoli: Demand for organic products is expected to surpass $30 billion by 2007.

Eat your broccoli: Demand for organic products is expected to surpass $30 billion by 2007.IT’S 7:45 ON A CLOUDLESS SATURDAY morning in downtown San Francisco. Chef Chris Cosentino is swerving his Toyota Matrix through tight corners to get to the Ferry Plaza Farmers’ Market before his favorite vendor runs out of organic radicchio. He forgot to advance-order it. “What the hell are you doing, you friggin’ shavin’ monkey?!” he hollers to a car idling in front of his targeted parking spot. He careens into another space, runs his hand through his spiked half-chocolate, half-vanilla hair, bounds out of the car, and grabs a Peet’s triple espresso before sprinting for the veggie stands.

At first glance, Cosentino seems an unlikely—nay, alarming—ambassador of Slow Food, an 80,000-member international nonprofit with 800 chapters in 52 countries. When he’s not cooking, the 32-year-old head chef at Incanto, a critically hailed Italian eatery in the city’s Noe Valley area, races mountain bikes—he won the overall solo in the 2002 24 Hours of Tahoe. His sponsors include Clif Bar and Red Bull. Is this a guy who does anything slowly?

That question points to one of the big misconceptions about the not so slowly burgeoning Slow Food organization, whose American branch, Slow Food USA, was launched in New York in March 2000, just months before Eric Schlosser published his best-selling Fast Food Nation, and has already grown to 12,000 members. Before I met Cosentino, I had heard only a little about the group. I knew they had a rather precious little logo of a snail. I knew they promoted esoteric artisanal foods and traditional modes of food production: Save the shagbark hickory nut!—that sort of thing. I pictured a bunch of tweedy, goblet-tinking foodies arguing the fine points of lactobacillus use in the preparation of Bulgarian buttermilk.

While this image is not entirely wrong, slow food is actually a lot more fun—and a lot more radical. The movement was born in Italy 18 years ago, when journalist Carlo Petrini organized a group of locals armed with bowls of penne to protest the opening of a McDonald’s near Rome’s ancient Spanish Steps. The charismatic Petrini unleashed brilliant diatribes against the 20th century’s loss of small farms, of healthy eating, and—more viscerally—of taste itself, as staggering numbers of foods went extinct. The movement, he wrote in the Slow Food Manifesto, would be an antidote to “Fast Life, which disrupts our habits, pervades the privacy of our homes and forces us to eat Fast Foods…. Fast Life has changed our way of being and threatens our environment and our landscapes. So Slow Food is now the only truly progressive answer.”

This turning of the tables has been an easy sell on the other side of the Atlantic, where culinary traditions are deeply ingrained and where Petrini, still president of the international group, is one of the 30 most influential people on the Continent, according to a recent Time article. But what works on the Mediterranean doesn’t always translate here. Siesta? Nada. We’re the country that invented the TV dinner and the drive-through. We crave Hot Pockets and call ketchup a vegetable. Most of us don’t know a fusilli from a fusillade. Let’s face it: If we can’t do slow food, er, quickly, the movement has as much chance of survival as the Galápagos snail.

Which is why it’s heartening, as well as appetizing, to watch Cosentino fly through the market. There’s no radicchio to be found, and he’s pissed. But then his sous-chef, Tracy McGillis, rings in on the polyphonic video cell phone and says she found some. Slow food, it turns out, isn’t about returning to the 19th century; it’s about thoughtfully participating in a marketplace for eccentric products, with the goal of getting people to consume them. Because if there’s one thing Americans are good at, it’s consuming.

“Slow Food is about two words: conviviality and sustainability,” says San Francisco chapter co-leader Carmen Tedesco, 54. To serve its “eco-gastronomic” mission, the organization essentially parties its way to enlightenment. Local chapters throw buyer-seller shindigs to introduce members to worthy crops and breeds and the eco-conscious farmers who raise them. The result: Those farmers stay in business, and the whole industry tilts a bit closer toward practices like organic production and more diverse cultivation.

By encouraging people to eat rare “heirloom” species, Slow Food keeps those species in domestication. Last year, the organization arranged 5,000 advance orders of rare and delicious Narragansett turkeys for Thanksgiving; the profits went to struggling farms, and the bird’s breeding population was doubled. Slow Food also aims to reconnect the masses to the food chain with initiatives like public-school gardening projects. “We’re not about gluttony and elitism,” says Erika Lesser, 30, the Brooklyn-based executive director of Slow Food USA. “We want people to have a viable alternative to industrial agriculture. We want to change the way people think about food.”

Given the explosion in farmers’ markets and a projected consumer demand for organic products that’s expected to surpass $30 billion by 2007, it’s a movement whose time has come.

Cosentino stops to chat up Clifford Hamada, of Hamada Farms. “When will you have Buddha’s hand citron?” he asks. (“It’s really ugly,” he says of the bitter-lemon-type fruit. “Looks like an octopus. I candy it or shave the fruit on a mandoline and sprinkle it raw on salads.”) This third-generation farmer, says Cosentino, sells dozens of kinds of peaches—dozens! Cosentino dashes off to check out some Braeburn apples, which he will use in a rutabaga-and-pasta dish.

“I seek out this food because it’s the best food,” says Cosentino, whose Incanto is a slow-foodie’s wet dream of hand-cranked pastas, house-cured salumi and mortadella, and a dazzling array of obscure Italian wines with impossibly long names. “But I also love these guys. It’s about relationships.”

Walking around the spectacular outdoor market, overlooking the Bay at the Embarcadero, I’m all over it. The conviviality! The healthfulness! The idealism! But then I remember that most of this pretty stuff has to be cooked, or at least prepared with some modicum of slicing, dicing, drizzling, and tossing. Can Americans actually be talked into putting aside those handy boxes and bags of processed foods?

“Look, you don’t have to do it all the time,” says Cosentino. “When I’m racing, I eat any old shit. But people can’t be afraid to cook. It’s easy—pick up fresh organic tomatoes, toss them with an incredible cheese, and put it on your pasta. Or buy a Crock-Pot, throw in some meat and fresh carrots in the morning, come home from work, and—boom!—it’s done.”

Mix Master: The Bosch Blender

Bosch blender

This is the mod whirl: Bosch’s badass blender

This is the mod whirl: Bosch’s badass blenderCall it the Boxster of blenders. The F.A. Porsche Designer Series, from German power-tool company Bosch, speedily purees the firmest frozen bananas, strawberries, and whatever you love in your smoothies. (Try our antioxidant-, protein-, and calcium-packed suggestions below, courtesy of sports nutritionist Monique Ryan.) Best of all, there’s beauty to this beast: The modernist-inspired brushed-aluminum housing keeps up kitchen appearances alongside your All-Clad saucepans and Viking range. $200; 866-442-6724,

The Saved-by-Chocolate Postworkout Smoothie

4 tablespoons sweetened cocoa » 12 ounces low-fat soy milk » 1/2 cup raspberries » 1 cup vanilla or chocolate yogurt

The Sunrise Smoothie

1 banana » 1 mango » 1/2 cup orange juice » 1 cup low-fat plain yogurt » one cup crushed ice

Low-Glycemic Berries and Cream

1/2 cup blueberries » 1/2 cup strawberries » 12 ounces skim milk » 1/2 cup vanilla yogurt » 1 tablespoon honey » 2 teaspoons flaxseed oil

Grow Your Own

food guide

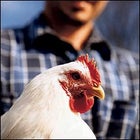

“Wait, can’t we talk about this?” A Stone Barns chicken on its way to the broiler

“Wait, can’t we talk about this?” A Stone Barns chicken on its way to the broilerDAN BARBER WANTS TO KNOW what the pork he’s eating for dinner ate before his pork, you know… became dinner. And he thinks you should know, too. So last May, the 35-year-old chef, whose Blue Hill restaurant, in Greenwich Village, brings seasonal, unique food to the city, took his fresh-‘n’-local food philosophy one step further: He reversed the farm-to-restaurant cycle altogether. Blue Hill at Stone Barns, a cozy, Provençal-style eatery at the center of the 80-acre Stone Barns Food and Agricultural Complex, in Pocantico Hills, New York, serves dishes like chicken roulade with red ace beets and Crescent duck with a stew of Napoli carrots to well-heeled locals and urbanites who, judging by the monthlong wait for a dinner reservation, are happy to make the 30-mile trip from Manhattan for a good meal and a lesson in sustainable agriculture. At least half of the food Barber serves is grown on the premises: The Stone Barns team, backed by a $30 million investment from community-farming advocate David Rockefeller, raises fruits, vegetables, herbs, and a coterie of free-roaming livestock. (The Berkshire pigs root and snort around in the woods the way their wild ancestors did in Europe.) When diners are finished, meal scraps are toted to compost piles, where the cycle of life begins again under the pitchfork of head farmer Jack Algiere. “I feed Jack and Jack feeds me,” says Barber, who hopes people will leave his restaurant not just full but enlightened. “Stone Barns provides an opportunity to discuss issues like the power of food choice, and to draw people’s attention to the land around them. Our goal is to provide a consciousness of how decisions you make buying food have an effect on the world you live in.”