Route 9W is the most popular recreational cycling route in the New York City region, which is, of course, the most densely populated metropolitan area in the United States. Riders pick up 9W just north of the George Washington Bridge and generally head up to the quaint villages of Piermont and Nyack where they stop for coffee and muffins. From there, they have the option of returning to the city or else continuing up to Bear Mountain State Park and beyond.

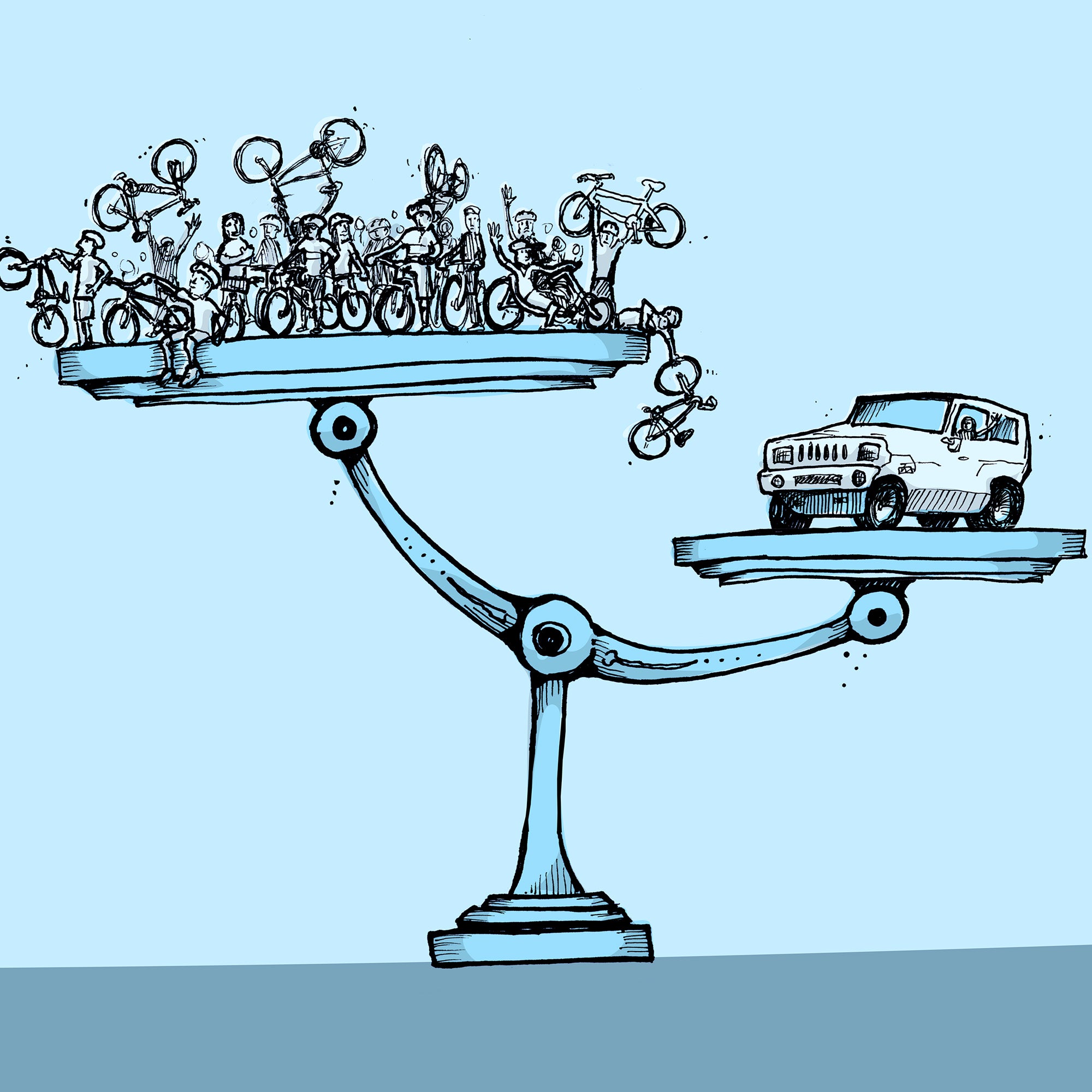

I’ve been riding 9W for decades now, but it was only during a recent weekend ride that I noticed something: cyclists comprise most of the traffic. On that particular day, I probably passed something like 100 cyclists a minute versus maybe like five cars.

Of course, the balance shifts more toward drivers during the week, but overall 9W sees a shitload of bikes. Yet for as long as I’ve been riding this corridor, cyclists have been treated at best as an afterthought and at worst as a nuisance. Over the past 20 years, I’ve seen virtually no infrastructure changes to increase cyclist safety or even convey to anybody that this is possibly the most heavily cycled route in the entire country.

I have, however, heard plenty of kvetching. Even though thousands of cyclists visit and spend money in these villages every week, all you ever read about in the news is how they do awful things, like talk audibly to each other while riding two abreast. Most recently, South Nyack residents , terrified by the prospect that cyclists and pedestrians might continue to visit in an environmentally friendly manner and spend money after dark. (Don’t worry, you’ll still be able to drive your car over and do donuts on lawns at any time of the day or night.)

Majority rules and money talks—unless you’re talking about people on bicycles, in which case we have a stunning capacity for ignoring them altogether.

It’s a similar situation along popular cycling routes everywhere: cyclists vilified for slowing traffic when in fact they are the majority of the traffic, or for somehow diminishing everybody’s quality of life by riding bicycles and patronizing local businesses. Furthermore, as more people commute by bike in cities across the country, it’s increasingly common to find streets where, during rush hour, you’ll see more bicycles than cars.

Yet it seems that whenever a new bicycle infrastructure proposal comes up, the first consideration—even before safety—is to what extent it might inconvenience drivers. In New York City, life-saving bike lane projects are subject to months and months of pointless public debate driven almost entirely by people whose primary concern is on-street car parking. Citi Bike sees something like 15 million trips per years, and the curb space taken up by one private car can provide docking space for eight publicly shared Citi Bikes. But before a new station is installed, planners must justify the “loss” of parking, even though it’s a net gain. Moreover, in order to preserve that precious car parking space, Citi Bike stations often wind up being installed on the sidewalk.

Majority rules and money talks—unless you’re talking about people on bicycles, in which case we have a stunning capacity for ignoring them altogether.

None of this is really surprising. After all, we’ve spend the last century in a state of complete surrender to the automobile, so of course we think putting cars first is normal. But it’s not normal—it’s absurd. And as more people begin riding bikes, the more apparent the absurdity becomes. It’s easy to blame a bike lane for the traffic jam you’re sitting in, but sooner or later, you can’t ignore all those cyclists whizzing by. And unless you’ve got carbon-monoxide-induced brain damage, eventually you’re going to have to confront the fact that the metal box you’re sitting in is just too damn big—bike lane or no bike lane. Same goes for the “loss” of parking. Invariably when a city proposes a new bike lane, there’s concern that it will harm local businesses by making it more difficult for customers to park. However, unless you’re selling building supplies or farm equipment, you need to confront the fact that expecting more and more people to arrive at your place of business in increasingly large vehicles is an extremely poor and ultimately self-defeating business model.

Oh sure, you can put more stuff in a car trunk than in a pannier, but that’s nothing compared to how many more bikes than cars you can fit on a typical shopping street.

Unfortunately, because this is the Land of the Freeway and the Home of the SUV, it’s going to be awhile before most of us come to realize how often it’s the cars that are actually preventing people from getting around. It’ll probably also take us awhile to realize that bicycles mean business, and that the people who ride them are indeed human beings who proffer currency in exchange for goods and services—just like drivers. As it is, thousands of cyclists stream up 9W every weekend and spend money in towns that often seem annoyed by them. Imagine how profligate cyclist spending would be if communities treated them as an asset rather than a blight.

Eventually there will be some sort of inversion wherein we realize all these things. But how many people need to be riding bikes before it happens? Do we need 20 percent mode share? 50 percent? 99 percent? Or will we keep prioritizing cars until the bike lanes are packed and there’s one guy driving down an empty six-lane avenue in a Hyundai?

Hey, we wouldn't want him to have any trouble parking.