Mike Kammerer piloted his black Mercedes SL600 convertible at 70 miles per hour down New Mexico Highway 599—dodging cars, barely slowing into a left turn past a cadre of state police distracted by an accident nearby—and powered the $130,000 driving machine through the Santa Fe Airport parking lot and straight onto the tarmac, stopping just under the wing of his 1935 Lockheed Electra 10-E. As I pulled in behind him, Kammerer, a youthful 61-year-old with a bushy head of white hair and the perpetually sunburned features of a ranch hand, stepped spryly out of his ride and bolted over to introduce himself. He was wearing a pressed and polished cowboy getup with a shield-size belt buckle, a denim shirt, and a black hat that looked big enough to lift his skinny five-foot-eleven-inch frame clear off the ground if a stiff wind kicked up.

A MAN, A PLAN, A PLANE: Mike Kammerer and his 1935 Lockheed Electra 10-E. the only flying sister-ship of the plane Earhart disappeared in 1937.

A MAN, A PLAN, A PLANE: Mike Kammerer and his 1935 Lockheed Electra 10-E. the only flying sister-ship of the plane Earhart disappeared in 1937.

“So, whaddaya think?” he asked as we shook hands. I wasn’t sure if he meant the car, his outfit, or the plane.

“Go ahead, stick your head inside,” he said, clearing up the matter by wrestling open the door to the legendary aircraft, one of only two existing models of the plane Amelia Earhart used in her tragically foreshortened attempt in 1937 to become the first woman to circle the globe. Last July, Kammerer paid the previous owner, Linda Finch, $1 million for the plane only an hour after he first laid eyes on it, gleefully beating out the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum for this rare prize. Finch had spent four years meticulously restoring it before completing her own successful circumnavigation of the world in 1997, roughly following Earhart’s planned route.

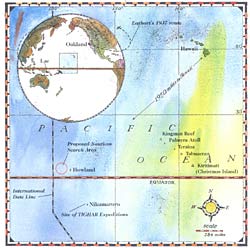

A few weeks after buying the Electra 10-E, Kammerer spent another $300,000 on a 1943 PBY Catalina—a lumbering floatplane similar to models the U.S. Navy used to search the Pacific for Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, after they failed to arrive at Howland Island, the refueling stop they were aiming for just a few miles north of the equator. (By that point they had completed roughly two-thirds of their journey, flying east and connecting the dots from California through South America, Africa, India, and Indonesia before disappearing.)

“I now have two historic planes in my possession that are part of the Amelia Earhart legacy—as investments,” Kammerer boasted. “For what, I don’t know.”

That’s the problem. The $1.3 million Kammerer invested was piled on top of $300,000 he shelled out in October 2000 for the media rights to a September 2001 expedition to a tiny, foot-shaped atoll in the middle of the Pacific, led by The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, or TIGHAR. Why? Because TIGHAR—a Wilmington, Delaware-based nonprofit made up of professional aviation historians, archaeologists, forensic anthropologists, and hobbyists who have volunteered their time to uncover a slew of World War II and other vintage aircraft—thinks the island may be the last resting place of the most famous lost pilot in history. Along with the media rights, Kammerer also secured the promotional rights to any shred of archaeological flotsam uncovered by TIGHAR. To date, that collection includes about 200 artifacts found on previous search missions, including the moldering fragments of an old shoe. Once, that shoe may have been attached to Amelia Earhart’s foot. Or maybe not. It’s hard to say.

If all of this sounds expensive at worst and speculative at best, it is. But Kammerer is dripping money made on speculation. Independent Television Network, the New York-based company he founded in 1983, has earned him millions over the years by buying blocks of time on television, repackaging it, and then reselling it to advertisers. In 1991 he turned daily operations over to a partner and skipped town for life on the range out West. This doesn’t mean he’s forgotten how to sell something. Speculation is exactly what he wants. Using hyperbole and good old Barnumesque razzmatazz, Kammerer is building his own El Dorado in the form of a missing airplane and its famous pilot. Which is to say, in his mind, finding Amelia Earhart’s plane is secondary to manufacturing an adventure on the back of a 65-year-old mystery. No matter who finds it, Kammerer intends to be there when it happens—media rights in hand, ready to sell. That is, if he can get anyone to stay tuned.

I followed kammerer back to his 20,000-square-foot adobe ranch home, set on 174 acres of rolling high desert outside Santa Fe. The house is a monument to the Old West. One room is filled with life-size statues displaying an array of Native American clothing; entire walls are festooned with turn-of-the-century riding chaps. We repaired to the den, where Kammerer hunkered down behind a massive black-walnut desk buried under papers, books, and bronze statuettes of cowboys on bucking broncos. He lit his corncob pipe and resumed his spiel.

It was now early August 2001. The TIGHAR expedition was set to leave later in the month for a four-week trip, but at the moment, Kammerer lamented, major media outlets were unimpressed, seeing only visions of Geraldo Rivera opening Al Capone’s empty vault. “I called a few friends and told them I had acquired the rights to this thing; the most I got was a yawn,” he said. “Discovery Channel was interested, then dropped out. National Geographic lost interest when I couldn’t guarantee that we would bring something back. Where’s the adventure in that? We may get a network deal this week. We have interest from CBS, but it all may go away.”

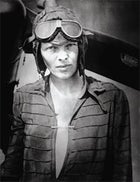

It’s difficult now to recall the frenzy that Earhart elicited when she took off from Oakland, California, on May 20, 1937, to fly around the world. She had already achieved celebrity status as the first woman to fly solo across North America and the Atlantic Ocean, and had set the female altitude record (at the time) of 18,415 feet. America, in the depths of the Great Depression and in denial about the coming world war, badly needed a diversion and happily followed every detail of her circumnavigation with rapt attention.

Earhart was attempting a feat of admirable strength and derring-do, and when she vanished off the screen before the newsreel ended, her legend only grew—and spawned a cottage industry that is thriving still. Over the last 65 years, more than 200 books have been published about her, from Amelia Earhart: First Lady of Flight to Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism. A host of Internet sites are devoted to her saga as well, including her estate’s site (), a trove of Navy search reports () and Amelia’s Mall (), a half-assed, Atchison, Kansas-based clearinghouse site for all things aviatrix. This perpetual buzz eggs on the news media, which keeps the dream alive by covering any blip that appears on the “Where’s Amelia?” radar. Just last summer, TIGHAR got a flurry of attention—coverage in The Washington Post, an interview on Today—when they announced that “anomalous pixels” in satellite images they had commissioned for their upcoming expedition seemed to indicate that something may be rusting away on that coral reef in the Pacific.

The intrigue, and the Pavlovian reaction it produces in daily-deadline newsrooms, is precisely what Kammerer hopes to turn into a larger triumph. “There’s all kind of mystery surrounding this thing!” he said, drawing out the words for effect. “There’s booooones, and sextant boxesssss. There are incredibly mysterious characters involved, and mysterious events. All this kind of stuff is more dramatic and interesting to me than just a piece of metal. Whether they find the plane or not is really incidental. Everybody wants credit for the damn thing. I don’t give a shit—I just want to make money and have a good time.”

A more forthright exhibition of obsession, hokum, and blunt honesty you could not hope for in a sales pitch. But Kammerer has a point: As mysteries go, Amelia Earhart is not a bad investment. The puzzle surrounding her disappearance ranks up there with the Kennedy assassination and the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby. The one indisputable fact in a goulash of circumstantial findings is that she took off from Lae, New Guinea, at 10 a.m. on July 2, 1937, bound for Howland Island, some 2,556 statute miles away. The rest is a riddle. Documentation uncovered by TIGHAR reveals that human bones, a woman’s shoe, and a sextant box were, in fact, discovered on Nikumaroro in 1940 by a British civil servant, with the bones later determined by a doctor on Fiji to belong to a short, stocky male of European descent. No one knows where those bones or the sextant box are today. Another popular though flawed theory is that Earhart was captured by the Japanese and later executed as a spy during World War II. Even Star Trek producers chimed in with an episode of the Voyager series in which Amelia is found in cryonic suspension on a distant planet.

But the two best hypotheses, the ones with the fewest unanswered questions and simplest conclusions, begin with the theory that the Lockheed ran out of gas while Earhart and Noonan frantically searched for their mid-Pacific pit stop. TIGHAR, headed by a former aviation insurance investigator named Ric Gillespie, has invested 13 years of research in Hypothesis No. 1: That the pair crash landed on or near Nikumaroro Island, about 360 miles southeast of Howland, and eventually died of thirst or injuries. Hypothesis No. 2, currently being investigated by the Nauticos Corporation, a Maryland-based deep-sea research firm, follows the logic laid out by the aviation historian and pilot Elgen Long, who surmises that Earhart ditched her plane 20 to 50 miles west of Howland Island and drowned.

No matter which hypothesis serious Amelia-heads subscribe to, looking for her ends up being the (relatively) easy part. The hard part—Kammerer’s part—is making it seem relevant and exciting to everyone else. In other words, salable. Talk to Kammerer about how he intends to make money on his deal with TIGHAR, which expires in December 2003, and his story morphs from week to week. Last summer Kammerer provided funding for a production company in Los Angeles called KBK Entertainment. KBK was not set up to produce Amelia-related product; however, when TIGHAR’s satellite images attracted a deluge of media attention, Kammerer got KBK involved in talks with National Geographic, which had expressed interest in possible magazine and TV coverage, as well as an IMAX film. In addition to talking to the networks and the Discovery Channel (which had already paid TIGHAR $50,000 for its story in 1997 to produce an hourlong show on an earlier expedition), Kammerer also contacted ���ϳԹ��� with a pitch for an IMAX film.

“When you have something like this that involves promotion,” Kammerer says, “you have to keep pushing the edges.”

But with no one interested in televising a TIGHAR expedition, Kammerer has been left to daydream about how much money he could reap from the discovery of Earhart’s plane. “I wouldn’t let a reporter or photographer within a million miles of it,” he says. “If the media want to cash in, they’re going to have to pay.” Beyond such bluster, his plans are very loose. If TIGHAR were to find the plane, Kammerer says, he would syndicate photos of it being exhumed from its watery grave to every news organization on earth. “I’m talking about that photo being worth $5 million!” he says.

Of course, finding the plane (difficult) and then safely recovering it (more difficult still) is expensive. Having already invested $1.6 million in the endeavor, Kammerer remains cagey about how much is too much.

“You can’t answer that question,” he says. “It’s not an issue of spending enough money. It’s a question of doing what it takes to intelligently pursue a goal.”

OK, but ultimately, what’s the point? Some people think there is one; some don’t. “It is the mystery of the 20th century,” says Dorothy Cochrane, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum who has followed TIGHAR’s and Nauticos’s exploits. But putting a value on something as esoteric as Earhart is nearly impossible. “Certainly there is a commercial value, there’s no doubt,” she says. “[But] historically it would be more important, because it would stop everyone from running around looking for her, and we could concentrate on who she was: a great aviator.”

Susan Ware, author of Still Missing, sees it differently. “Part of me wishes they would just leave her in peace,” she says. “We should be looking at the significance of her life, not the circumstances of her death.”

For Kammerer, such concerns are just part of the challenge. He can sound a tad unhinged when he rants about the lack of vision and bravado he’s encountered in TV-land. But when asked why he’s even bothered getting involved in this three-ring circus of legend, mystery, and discovery, his tone changes to that of a kid—albeit a very rich kid—showing off the coolest new toy on his block.

“I think the idea that, after all these years, someone who knows nothing about archaeology can assemble a world-class team and can go out and solve an international mystery—I think that’s neat,” he says. “It’s a neat thing.”

If kammerer has a polar opposite, it’s Ric Gillespie. Five-foot-ten with graying blond hair and a beefy build, Gillespie, 54, cuts a swashbuckling figure in the geeky realm of airplane buffs. Inside TIGHAR, he’s known for being highly opinionated but is also respected for his diligence and deliberate nature. Since 1989 Gillespie has made six trips to Nikumaroro to search for artifacts. So far he has recovered a load of curious stuff, ranging from parts of a woman’s size nine-narrow shoe to pieces of Plexiglas that “are consistent with that of Earhart’s Lockheed Electra.”

“There’s no doubt in my mind that we’ve found the right place,” Gillespie told me from his office in Wilmington, a month before the sixth expedition. “I can convince academics all day long. But to put an icon like Earhart to rest, we have to find definitive evidence. We need the Any Idiot Artifact.” Meaning the one thing that any idiot would accept as proof that Earhart’s crash site had been found—in this case, the plane or some kind of DNA evidence. “Where it exists, I don’t know,” he said. “But it doesn’t really matter; it’s so damn much fun to look.”

Gillespie’s most tantalizing scrap of evidence can be seen on a TIGHAR-produced videotape that Kammerer showed me. (There’s also a book, Amelia Earhart’s Shoes, in which four fellow TIGHAR volunteers set down their research in painstaking detail.) After various shots of Gillespie pointing at maps of Nikumaroro and indicating hot spots, he displays a satellite photo, taken in April 2001, that shows a rust-colored speck clinging to a reef on the western edge of the island. Gillespie speculates we may be looking at rusting plane parts lodged in coral crevices. This is followed by footage of an interview Gillespie conducted in 1999 with a Fijian woman who briefly lived on the island with her family in 1940. Asked about possible wreckage on Nikumaroro, the woman says she remembers seeing the remains of an airplane. Asked where, she eerily points to the same spot on the map where the rusty pixels appeared in the sat photo.

It’s circumstantial but, to Gillespie and Kammerer, intoxicating. Since making the media-rights deal with Kammerer, however, Gillespie has been forced to adjust his pace to handle the barrage of ideas drummed up by the TV advertising mogul. Last August, just before Gillespie and his 12-person archaeological team were scheduled to depart for Nikumaroro, the captain of an Australian-based salvage tug discovered TIGHAR’s search plans on the Internet and decided to take a look for himself. Though the salvager was unsuccessful, word of the attempt set Kammerer on a crusade to protect his investment in undiscovered booty from what he called “unauthorized trespass.” He hatched a plan to hire professional sky divers to tandem himself, a film crew, and a former Miss World USA named Natasha Allas onto the island, along with several thousand pounds of supplies to sustain them for three weeks until the TIGHAR ship arrived. Natasha, he explained, would be there to act as a spokesmodel for the expedition.

“I’m doing this to protect the archaeological and ecological sanctity of the island,” he elaborated. “I’m also wondering what it might pay off as a publicity stunt. I’d like Natasha to go because the fact that a woman would do this makes it more dramatic.”

Gillespie was…unimpressed. If the scheme went bad, he would be forced to suspend his expedition to rescue the hapless sky divers and prevent Nikumaroro from becoming a more ridiculous version of Survivor.

“The phrase ‘loose cannon on a rolling deck’ comes to mind,” Gillespie said of Kammerer. “But we took his money. All of this year’s research happened because of Mike’s participation, bless his heart.”

The skydiving plan never left the ground, but it would not be Kammerer’s last Homeric poke at contriving an adventure.

So what about Hypothesis No. 2? Good question. Remember Elgen Long? In 1999, with 25 years of research and 40,000 hours of flying behind him, Long published Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved. The book theorizes that Earhart’s Lockheed Electra 10-E lies in a 2,000-square-mile quadrant of the Pacific under 17,000 feet of water. Nova, the PBS adventures-in-science show, was impressed with Long’s research and in the fall of 1999 struck a deal with the Nauticos Corporation to film an undersea expedition to find the plane.

Nauticos brings a wealth of ocean-exploration knowledge to the endeavor. David Jourdan, a 47-year-old former Navy submariner and the company president, has logged 20 years searching the seas for lost vessels, and his company has made several discoveries, including the Japanese aircraft carrier Kaga, sunk in 1942 during the Battle of Midway, and the Israeli submarine Dakar, which sank after a collision in 1968. Tom Dettweiler, the company’s 50-year-old director of ocean operations—who worked with Robert Ballard on the discovery of the Titanic—was tapped to run the Earhart expedition.

Nauticos’s plan depends more on technology than forensic sleuthing. A piece of side-scanning sonar equipment called the NOMAD 6000 is to be hung from a five-mile-long fiber-optic cable attached to a surface ship, which will then patrol up to 800 square miles of ocean west of Howland Island. The cable alone weighs 15 tons. Using sound to sweep the ocean floor—in that area, a relatively flat plain—the sonar sends the information to a computer on board the ship, which then translates the echoes into an image of the bottom. After collecting the sonar data, an ROV (remotely operated vehicle) equipped with lights and a camera will be sent down to get a better look. At 17,000 feet, little oxygen is left in the water to corrode metal, and because of the sea floor’s smooth contour, Nauticos expects the gear to easily register any plane-size lumps. But it won’t be a cinch: Jourdan compared their search technique to dangling a piece of dental floss from a 40-story building.

Still, he is totally confident about Nauticos’s chances. “By our analysis, there is only a 15 percent chance that we won’t find it,” Jourdan says. “We’ve never failed. If the premise that she did run out of gas and went into the water is correct—if we do our job—then our chances will be very high.”

Of course, there’s a catch: Nova could only finance the film, a fraction of the $4 million search-and-recovery costs, so Nauticos had to find another benefactor. Enter Mike Kammerer—again. When he first heard of the Nauticos expedition, last summer, Kammerer had a realization. “One of these guys is gonna find her,” he said, referring to TIGHAR and Nauticos. “In this deal, you better cover your bet.”

Last August, Kammerer invited me along on his mission to strike a deal with Nauticos. We hopped into a Cessna turboprop that he uses for personal transportation and flew to Los Angeles. It was an affair designed to impress: Kammerer footed everyone’s bill for an overnight stay at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills.

Over dinner that night, Kammerer and Jourdan shared their divergent views of the Earhart project, with Kammerer emphasizing the need to create media capital that could make Nauticos famous, and Jourdan explaining the many difficulties involved in a deep-ocean search. At one point Kammerer excused himself, explaining that he needed to make a phone call. When he returned about 20 minutes later, he dropped a check for $300,000 onto the table, along with a folded piece of hotel stationery roughly outlining the strings attached. He promised another $2.2 million within months.

“So, do I have your attention?” he asked, a little smile creeping out from behind his poker face. The deal was simple: Kammerer would cover the cost of finding the plane if Jourdan would sign over the media and merchandising rights to the expedition, and anything it might find, to him. Jourdan balked. Even with an 85 percent chance of finding the plane, the 15 percent possibility of landing facedown on the cold ocean floor—all under the glare of Kammerer’s media rhetoric—was enough to scare him off.

For Jourdan, the real value is in actually finding the plane, not in creating media capital. “What he was saying was, ‘Go to work for me, find my airplane, and go away,'” Jourdan later said of Kammerer’s offer. “We’re not here just to have fun, we’re here to create a long-standing, self-sustaining ocean exploration project. Why should I sell out my life so this guy can have fun? There’s a much bigger mission here, and that’s what we’re after.”

Jourdan returned the $300,000 check and pinned the handwritten promissory note to a bulletin board in his office as a memento.

It was a long flight back to Santa Fe. By mid-September, Ric Gillespie and his TIGHAR team had returned from Nikumaroro with some moldy trinkets, but little else. That cluster of rusty pixels? Red algae. Nevertheless, like the true Amelia-obsessive that he is, Gillespie refused to acknowledge it as even a minor setback.

“This was the best expedition yet,” he told me last fall. “There were no Indiana Jones-type discoveries, but we have found some artifacts that may identify who the castaway was.” So who was it?

“We’re hoping there is something here that will point to Earhart,” he said. “[But] the proof isn’t there yet.” Gillespie and other TIGHAR team members will spend the next two years poring over their latest finds and contemplating another trip to Nikumaroro—Kammerer or no Kammerer.

Speaking of whom… The last time we spoke, he’d cooled on Hypothesis No. 1. Ever the opportunist, Kammerer is now making noises about putting together his own deep-sea expedition—using Elgen Long’s book as his guide, naturally—to beat the Nauticos guys to the punch.

“I’ve talked to every legitimate expert on the Amelia thing,” he told me. “There is absolutely no question that she’s in that 2,000-square-mile area defined by Elgen Long. Since she’s at the bottom of the sea, there’s nothing left but to go and get her.” When I asked him how this might affect his media-rights deal with TIGHAR, he all but said it had been scuttled. “I even believe I could get Ric Gillespie to admit that to me in private,” he said, referring to the veracity of Hypothesis No. 2. “I know she couldn’t be anywhere else—it’s impossible!”

Gillespie remains bullish about TIGHAR’s chances, though some might call it denial. He laughed at Kammerer’s assertion. “I’d be very surprised if somebody could convince me that the landing at sea is the best-supported hypothesis,” he said. “There was never wreckage found, not even an oil slick, and nothing even washed up on beaches. Going down at sea would be the logical conclusion if nothing else happened, but there is abundant evidence that something else happened.” When I asked him if he’s worried about the Nauticos expedition, Gillespie barked, “Nauticos hasn’t done anything! They don’t have money to do what they want to do.”

Guess what? Dave Jourdan does not agree. “There’s only one place left to search for Amelia’s plane, and it’s going to get done,” he told me as this article went to press. “I hope it’s us.” Jourdan claimed that he had several potential investors sitting on the fence, and definite plans to drag his sonar gear across the ocean floor sometime this winter, but he hadn’t closed the door on Kammerer’s offer completely. “We’re getting closer all the time,” he said of his search for cash. “I’m looking for someone who will share the fruits of what we find, not take them away. [Kammerer] sees his money as the most important thing when it’s the least unique. Lots of people have money.”

Predictably, Kammerer believes that both Nauticos and TIGHAR need him more than he needs them. And he expects neither of them to make a dime on the Earhart search, even if they find the plane. Relying on the likes of the Discovery Channel, Nova, or some other documentary-film production operation for income is, he now says, a financial dead end. “The people involved in the search for Amelia have not been effective in raising money, because the way they anticipate making money doesn’t make sense to people like me,” he declared.

But at this juncture, what, if anything, makes sense in the race to find Amelia Earhart? “What does make sense?” he shot back. “I don’t have a clue. But I have some guys with me that have some ideas.

“It’s not a question of losing,” he added. “How can you lose in this thing? It’s such a great adventure! The challenge for me is, can I control the snowball, or will someone else cash in?”

With Kammerer, it’s all about honesty. To that end, he recently made an investment in a small magazine company called Circa Media, which publishes Archaeology Today and Dinosaur Magazine. In February, Circa will publish a one-shot magazine called—what else?—Amelia. Kammerer claims it will be the definitive authority on the search for her and her plane. How could it not be? Stephen Titus lives in Colorado. His last article, on New Mexico’s Cerro Grande forest fire, appeared in September 2000.