Ironman is a pretty enlightened place when it comes to gender equality. Men and women have enjoyed equal prize purses at Ironman's World Championship race in Kona┬ásince the event started offering cash to winners in 1986. And at each of the 100 Ironman races around the world, the pro men and women split winnings equally. But thereÔÇÖs one major sticking point: there are 15 more slots for pro┬ámale competitors at IronmanÔÇÖs World Championship in Kona than there are for women. In a recent statement, , defending the decision to not close the gap. But itÔÇÖs time things evened up for our pros, for the greater good of the sport. ┬á

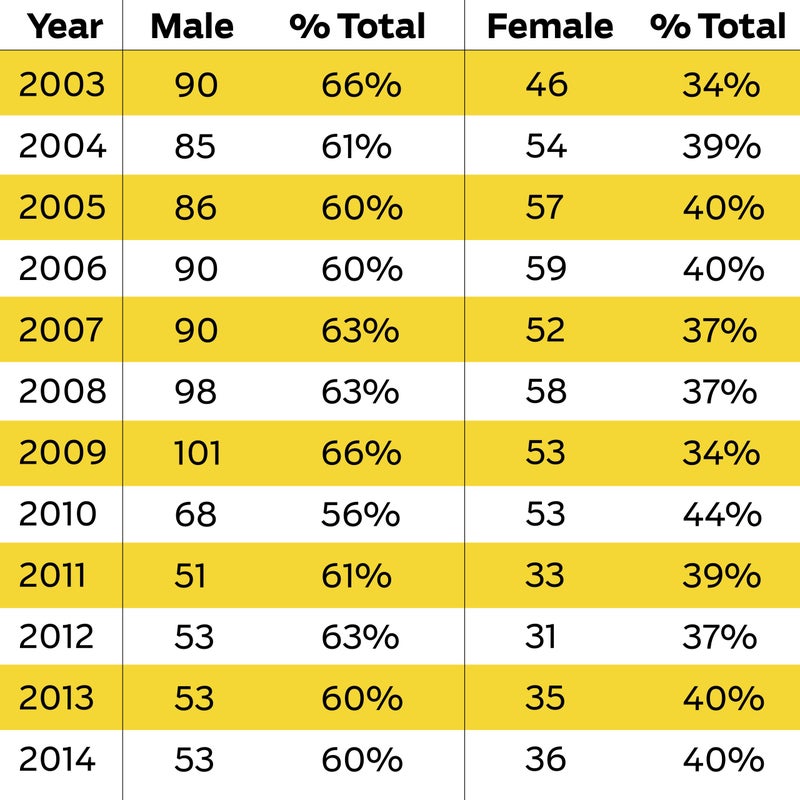

Throughout the eventÔÇÖs history, more male than female pros have toed the line at Kona. (See chart below.) Before 2011, pro Kona slots totaled 10 percent of the total number of slots assigned to a particular race. If there were 100 total Kona slots awarded at the IM Wisconsin event, for example, 10 of those slots would go to pro athletes. The number of males and females who earned a spot was then allocated based on the percentage of male and female pros at that specific event. Say 100 pros raced, for exampleÔÇö60 men, 40 women. In that case, six men and four women would qualify. Because more men than women raced, more men earned a spot at Kona.

Kona Pro Starters 2003-2014

But in 2011, World Triathlon Corporation, the private equity-owned company that puts on the global Ironman series, instituted┬áa more complicated points-system approach for pros.┬áWith an expanding global race portfolioÔÇöand each race offering Kona qualifying spotsÔÇöWTC adjusted the pro qualifying process to get only┬áthe most competitive athletes on the Kona start line. With the new points system, the number of pro qualifiers shrank from a peak of 156 pros in 2008 (98 men, 58 women) to 89 pros last year, while the overall number of Kona competitors rose from 1,867 to 2,301. Now the top 50 pro men, as determined by the newer points-based ranking system, get to go to Kona. But only the top 35 women do. For a professional world championship event, the numbers seem arbitrary.

ÔÇťImagine Wimbledon without 64 men and 64 women,ÔÇŁ says Ironman champion Sara Gross, who holds a Ph.D. in WomenÔÇÖs History. ÔÇťThere is no example in sport that I know of where the number of┬áwomen allowed at a world┬áchampionship┬áevent is decided based on┬áparticipation┬ánumbers whether at the elite level or women generally. In some major marathons in the U.S., we have more women participating than men. So should we limit the number of elite males who can enter that marathon? That┬ásounds ridiculous, right?ÔÇŁ

Gross is a key driver behind a social media and letter-writing campaign called 50 Women to Kona that calls for equal slots for women as for men. The effort is , both male and female, including four-time Ironman World Champion Chrissie Wellington. Gross asks why triathletes should accept the inequality in Kona slots┬áwhen theyÔÇÖve never had to accept unequal prize purses. ÔÇťWe are so close to having it all,ÔÇŁ she says. ÔÇťItÔÇÖs┬áas if┬áwe are stopping 100 meters from the finish line.ÔÇŁ

WTC says the logic for the current disparity in Kona slot allotments is based on gender representation in the Ironman pro athlete ranks. In 2014, there were 739 pro men and 381 pro women in the Ironman system. Put simply, the men get 15 more slots than the women because they nearly double the women in numbers.

That's not all.┬áIronman CEO Andrew Messick says giving women more slots┬áwould actualy hurt pro women in the long run┬ábecause he believes those slots will go to slower pros who might not be able to┬ábeat the age groupers. ÔÇťHaving a separate, lower standard for women sends the wrong message and would be the first time in Ironman history that we are creating┬áone,”he says.┬áWTC pointed out in an email that in past years, such as in┬á2010, when the pro field was much larger,┬áÔÇťmany pros were beaten by the age-group fieldÔÇöresulting in concern that the World Championship was losing its prestige.ÔÇŁ

Furthermore, Messick says the overwhelming demand for Kona slots across all divisionsÔÇöpro and amateurÔÇöcreates the need to approach slot allocation in a highly systematic way.┬áTacking an additional 15 entries onto such a large┬árace (last year, it┬áhosted 2,301 athletes), Messick argues, is not easy. He claims┬árace venue is at capacity, making it difficult to simply add more slots. Additional slots would have to come from the pro men or age groupers.

ÔÇťOnly three percent of age-group athletes qualify for Kona, and an overwhelming number of people who qualify for Kona take their slot,ÔÇŁ he says. ÔÇťThe groups of athletes that have the most people participating should have proportional representation in the world championship.ÔÇŁ┬á

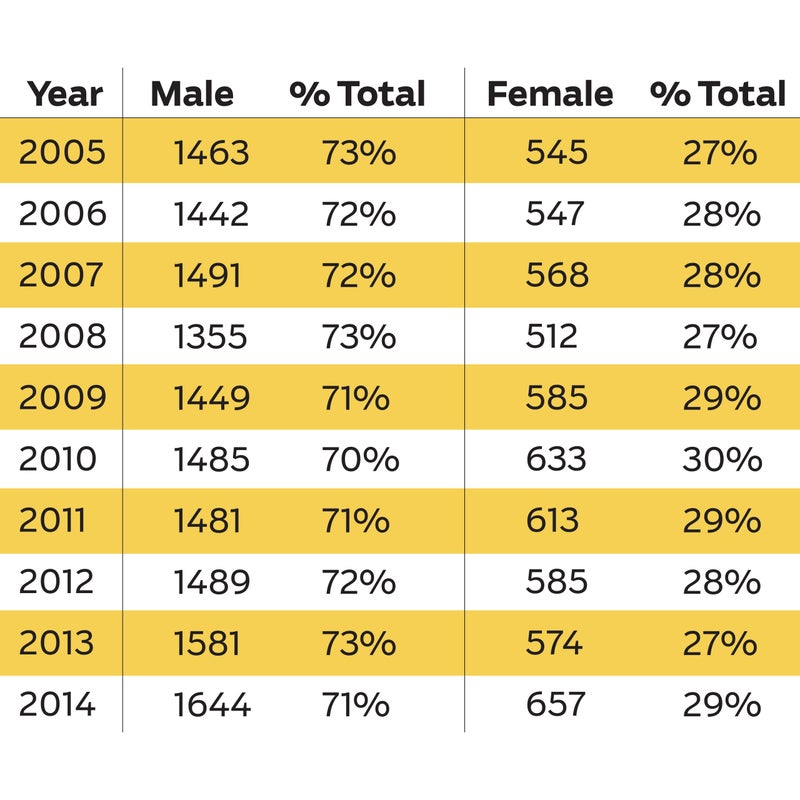

Because there are far more men racing than women (most races have a 70-30 split), Messick believes arbitrarily creating a system of quotas for the pro women, when only the top three percent of age groupers qualify,┬áis wrong. ÔÇťWe feel that itÔÇÖs antithetical to the spirit of Ironman,ÔÇŁ Messick says.

Kona Competitors 2005-2014, By Gender

That gets us to the core of the debate between the WTC and its pro athletes: whether or not the pros should receive special consideration because of their elite status.

Amateur triathletes in Kona arenÔÇÖt there to earn a paycheck. For pros, who make up only four percent of the field, the stakes are very different; for many of them, their livelihoods are linked to an appearance in Kona, the most high-vis event of the year. The pro women aren't buying any of WTC's argumentsÔÇöthat 15 extra female racers will diminish Kona's prestige, or┬áthat adding 15 slots is unfair to age groupers.┬á(WTC did, afterall, add 145 age group┬áKona slots between 2013 and 2014.)┬áThe three-percent rule or something similar, they argue, should not apply to them.┬á

The pro women I spoke with say adding the slots will not lower the bar for pro women. Instead, they believe just the opposite will happen: equivalent representation in Kona will ultimately raise the profile of the sport and draw more womenÔÇöan endgame that would tremendously benefit IronmanÔÇÖs bottom line, considering that 81 percent of people who raced Ironman events in 2014 were male. Opportunity breeds growth, they say, and Ironman can stand as a powerful and inviting example of total gender inclusivity by closing a gap of a mere 15 spaces.

While Messick seems to understand the sentiment, heÔÇÖs not sold on it. ÔÇťI appreciate the belief that ÔÇśif you build it, they will come,ÔÇÖ and I would be curious as to whether thereÔÇÖs any evidence to support that,ÔÇŁ he says.┬á

But maybe the fight for Kona slot equality isnÔÇÖt about hard proof or ratios. Maybe pro women like Gross have a case built on an ideal that canÔÇÖt be measured or countered in simple math.

IÔÇÖm not advocating for 500 more slots for the women (i.e. adopting a sweeping policy of equal Kona slots for men and women in both amatuer and pro ranks), but I do believe that equal representation of pro women is the right stepÔÇöand messageÔÇöin laying a foundation for future sustainable growth of our sport.

Ironman has been a true pioneer in holding up women to a new standard, helping them dream a little bigger and enabling significant earning opportunities as they pursue their triathlon goals. Taking the final step by providing equitable professional representation at the world championship can close the circle and set us all up for success.

ÔÇťKona is about the experience of everyone coming together and supporting that passion for Ironman,ÔÇŁ says Julie Moss,┬áthe woman whose is largely credited with bringing the fringe event into global consciousness. ÔÇťThereÔÇÖs a part of Ironman thatÔÇÖs about heart and soul. I say, letÔÇÖs err on the side of heart and soul.ÔÇŁ

Julia Polloreno is the editor-in-chief of Triathlete and , and a founding board member of , the Ironman/Life Time Fitness initiative to grow womenÔÇÖs participation in the sport.