There’s a lot about cycling that bewilders the layperson, but perhaps the aspect of it they find most confounding is the price of a great bicycle:

“Wait, it cost what? That’s almost as much as a car!”

Yes, it’s true. A really exquisite new bicycle can cost as much or even more than a shitty old car. Sure, bikes don’t have to be expensive to be great, and the resourceful cyclist knows how to conjure up something from nothing out of the parts bin down at the bike co-op. But for the average consumer, whether you’re talking about a state-of-the-art race bike or a supremely functional utility bike, you’re easily looking at a few grand.

So why is the car the go-to metric for bike prices? Granted, there’s some overlap between the two in that both have wheels and can be used to go places, but beyond that, as machines, they have very little in common. Moreover, we don’t seem to get hung up on car prices when it comes to other modes of transport. For example, airline flights can be pretty expensive too, but I’ve never heard anyone incredulously exclaim, “You paid how much to fly to Sydney? You could have bought a pre-owned Ford Focus!”

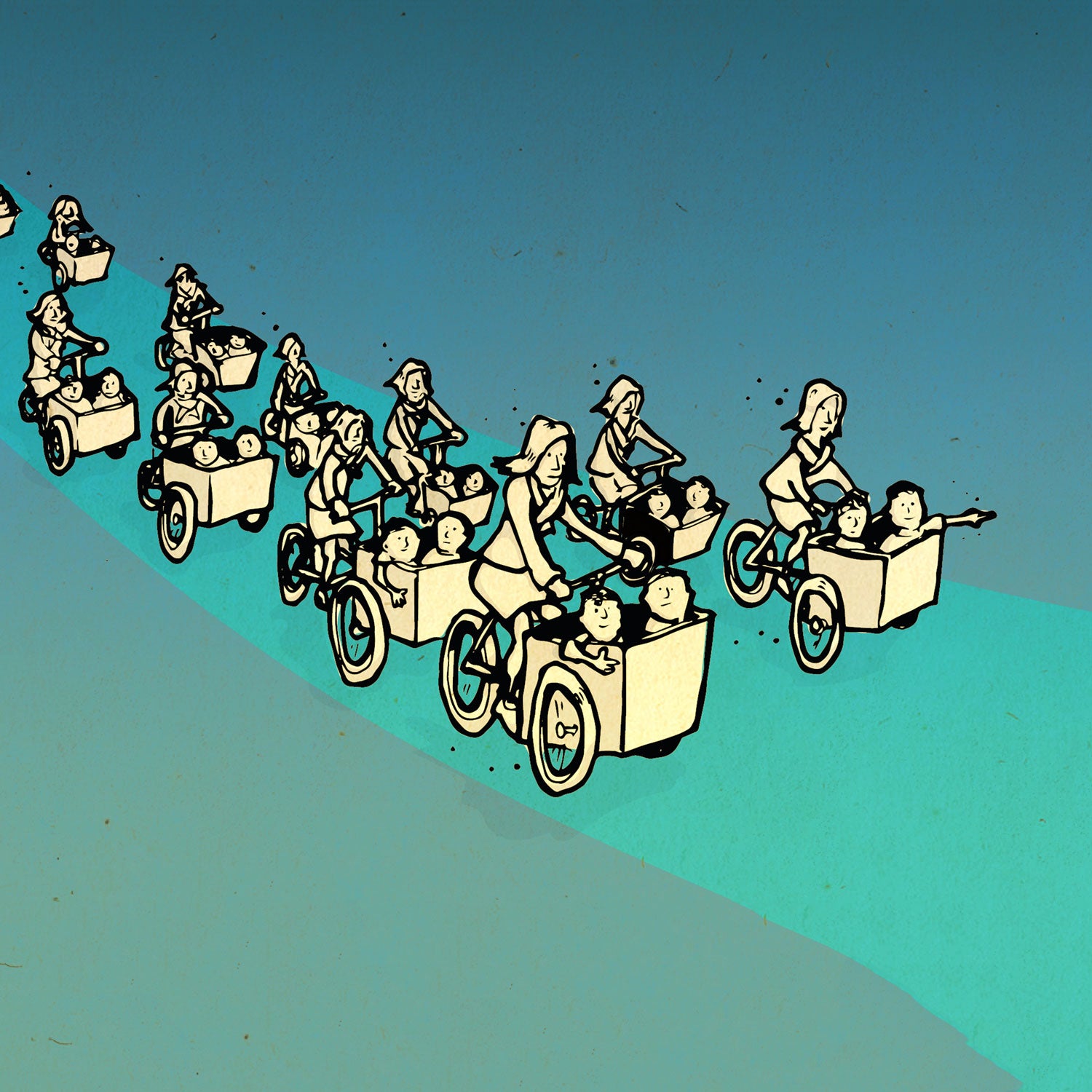

Nevertheless, not only do we think paying Craigslist car prices for an amazing bike is crazy, but we also consider doing so to be the exclusive domain of the privileged set. When it comes to most durable goods, we have little trouble understanding that you’ve generally got to spend more to get more, and that if you use something heavily and often you’ll inevitably amortize that higher up-front investment. This is why if you fish nobody’s going to begrudge you a good boat, and if you entertain a lot, nobody’s going to accuse you of being entitled because you sprang for some solid outdoor furniture and a quality barbecue grill. Yet spend a couple thousand on a cargo bicycle you can use to haul all that meat and beer from the store without having to pay for gas and insurance and suddenly you’re a monied elitist—unlike the decent workaday folk who spend ten times that for a Honda Accord.

Indeed, expensive utility bikes are especially offensive to the American sensibility. Even someone who hates bikes can understand wanting to own a flashy, expensive racer that’s built for speed. A cargo bike, however, is so unlike the bloated pickup trucks and SUVs we’ve come to conflate with practicality that it comes off as a bauble for the soft-handed set. Therefore, paying to own one comes off as a sign that you’re a self-indulgent person free from any real-world concerns.

You hear this all the time in anti-bike lane discourse: a small, vocal group who rail against the invading hordes of bicyclists who will steal the neighborhood from them. Generally this “community” paints the bicyclists as some form of spoiled “other” traipsing blithely through life, such as transplants, hipsters, or rich people, or often all three at once. (The exception to this is when the neighborhood is already wealthy, in which case they paint the bicyclists as reckless louts who will clobber senior citizens and destroy the local businesses.)

A cargo bike is so unlike the bloated pickup trucks and SUVs we’ve come to conflate with practicality that it comes off as a bauble for the soft-handed set.

This even happens in the world capital of bikes-as-transportation, the Netherlands—at least according to . Supposedly in Rotterdam the “bakfietsmoeder,” or cargo-bike mother, is a hated agent of gentrification and a harbinger of “urban change” and “affluence” who spirits her brood away from the unwashed working class in her designer box bike. Then there’s her male counterpart, the “bakfietspapa,” or cargo-bike dad; basically just a simpering wuss who does craven, un-manly things like working part-time and helping raise the children. As for the cargo bikes themselves, the article explains that they were once associated with poor laborers, but now they’re coveted by rich douchebags who use them to take their children to mamby-pamby schools and steal the city from the deserving, one boxload at a time.

Hey, I get it. Burning gas means you’re doing something important, and it’s easy to dismiss people on bikes as spoiled brats who don’t take life seriously enough. They move efficiently, unfettered by the traffic in which good hardworking people have the integrity to languish. Their brows are not furrowed by the stress and expense of car ownership and dependence. They are generally healthier and . Most egregiously of all, they seem…happy. And nothing arouses more suspicion than happiness.

But there’s also something more insidious in all of this cargo bike contempt. It’s not just disdain for bikes, or even for wealthy people on bikes. Ultimately it’s disdain for anything that doesn’t have balls, or at least the appearance of balls. Any male cyclist who’s been on the receiving end of harassment knows it’s always about impugning your masculinity. And, paradoxically, women on bikes have to deal with from people who think what they’re doing is too dangerous. Granted, the Netherlands doesn’t share our notion that the roads are the exclusive domain of the big-balled, but the sentiments expressed in that Atlantic article come off less as anti-bike than they do as anti-mom.

Gentrification certainly comes with a whole bakfiets full of issues, but it would be a real shame to let bikes—cargo and otherwise—become collateral damage in the debate surrounding it. Drivers kill pedestrians at in poorer neighborhoods. Such neighborhoods are also often underserved by transit, which means residents are subject to the crushing economic burden of car dependence, particularly predatory auto lending. Meanwhile bikes are relatively cheap, efficient, and practical, the concomitant infrastructure calms traffic and reduces injuries and fatalities, and the proliferation of bike share means that increasingly you’re no longer subject to the upfront cost of owning one. What a profound waste it is then for the closest thing you’ll ever find to a free lunch to get all bound up in the notion that it’s something for rich elitists, or that accommodating bikes somehow means surrendering a neighborhood, when if anything bikes help empower a neighborhood.

Ultimately, we all need to grow a pair. (Of wheels.)