I looked at the menu at a booth in Morg’s, a diner in Waterloo, Iowa, on a cold morning in January, sure of one thing: the joke I was going to lob at my friend Dave near the end of breakfast. I was not sure the joke would actually be funny, but I was definitely going to say it.��

Dave and I get together almost every time I’m back in Iowa visiting my parents. He was my last roommate while living in the state, before I left to move west��in 2002, a shift of geography that rerouted my life completely. We’ve stayed in touch since then, some years the thread of communication��thinner than others��but still there. Most of the time, when I come back, one or both of us has to drive more than an hour to make a meeting happen, just like this time.��

Dave walked in, sat down, and said, “I think the last time we were here, I had just bailed you out of jail, a few blocks from here.” I said I was 100 percent sure that was correct, and I don’t remember if I even ate anything that morning in March 2002��or just sat across from him and smoked Camel Lights, which you could do indoors in Iowa then. The night in jail followed what would be my last night ever drinking alcohol, which is a separate, long story. In my fuzzy memory, I’d called Dave from the jail phone��and told him I was stuck there until I could raise $3,000 in bail. I’m certain I called him instead of my parents because I had disappointed them enough over the past few years, and Dave would be less disappointed in me��but hopefully still understand.��

Dave showed up at a bail-bond place with the title to his car and $300 I might or might not be able to pay him back at the time, and I got to go home that morning instead of sitting in jail with a headache and the gut-punched feeling of what recovering addicts call rock bottom.��But first��we went to Morg’s for breakfast. Dave paid the bill, and before he headed to his shift waiting tables at a restaurant, he dropped me off back at the house we shared with our friend Nick. Over the next few months, and then years, my appreciation for what Dave did for me began to multiply.��

The simplest way to explain it is: at��that time in my life, I was an irresponsible person who was good at getting in trouble. I asked Dave for help, and he made a bet on me: his car. In order for him to keep his car, I had to change. Which was a big gamble at the time. As has since been pointed out to me, there’s a time and a place to cut someone off with tough love��instead of potentially enabling them to wreak further havoc. I don’t know exactly what Dave was thinking then, but I’m glad he bet on me that one last time.��

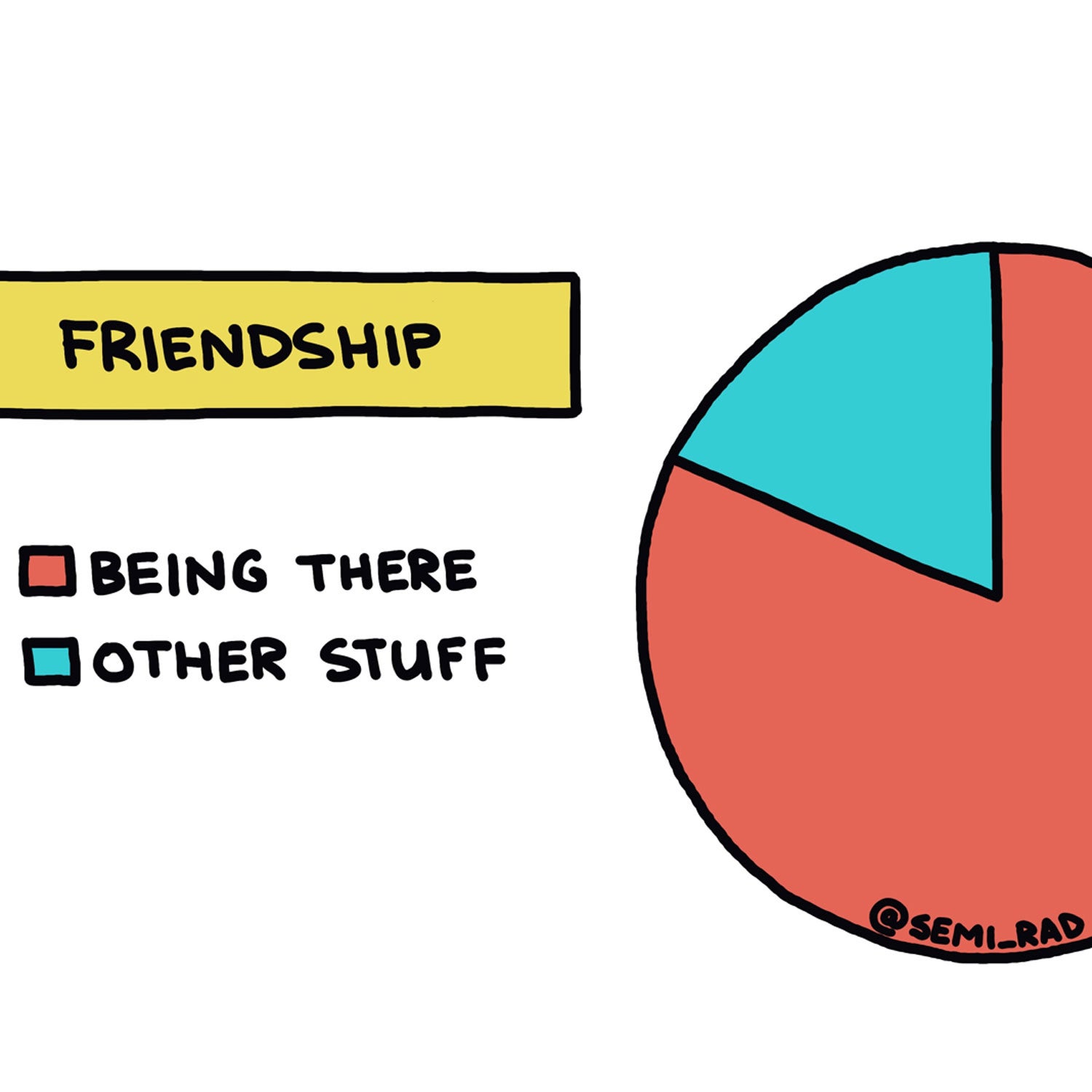

Over the years since, I started to see Dave’s gamble as a symbol, or more accurately, the defining act of what constitutes friendship: showing up. I would argue it’s the most important element of a friendship. If your friend needs a groomsman or a bridesmaid, help moving a couch, someone to talk to about something difficult they’re going through, a ride home from the airport, you show up for them.��

A few months after Dave bailed me out, I moved to Montana��and eventually Colorado. Every year��I tried to remember to text Dave and say, “Thanks for bailing me out in March 2002,” just so he knew I never forgot it��and still appreciated it. The more I got into the mountains, the more I valued the people who showed up, whether it was on the belaying end of a climbing rope, a promise to switch their beacon to search mode and dig like a motherfucker in the event of an avalanche, or just arrive ready at the trailhead at the time we agreed upon, even if it was four��in the morning.��

Dave and I both eventually found our way to a common sport:��trail running. I casually mentioned getting together for��a week in Rocky Mountain National Park last��summer.��I was working on a guidebook and thought that��maybe he could come out for a few days and join me for some hiking and trail running. He decided to join me for ten days, and to my great joy, we got Dave up his first fourteener, Longs Peak, which is no walk in the park when you’re coming from the flatlands and you’ve��spent almost zero time navigating talus and��scrambling��in thin air 13,500 feet higher than the house you live in.��

The more I got into the mountains, the more I valued the people who showed up.

When I was back in Iowa over the holidays, when Dave texted about getting together, I suggested Morg’s. As we sat in the booth catching up, I tried to remember what it had looked like in 2002, the last time we were there together. I thought maybe it had been more dimly lit, but I wasn’t sure. I remembered the pancakes, which almost hung off the edges of large plates. The server dropped off the check, and I snatched it from the table before Dave could even get a finger on it. He made the face you make when your friend insists on buying breakfast, and then I said a line I had been thinking about for days, or maybe 17-plus years:

“I’ll get it. You got it last time.”��

We both laughed, more than was actually appropriate for the quality of the joke, and then I went on to say something like, “Come on, you bailed me out of jail, risked losing your car, changed the course of my life, taught me one of the most important lessons about friendship, etc., etc., etc., so the least I can do is pay for your breakfast,”��which is, I believe, an advanced-level sarcastic-midwesterner way of saying to another midwesterner, genuinely but packaged inside a joke,��thanks for being there for me.

Brendan Leonard’s new book,��Bears Don’t Care About Your Problems: More Funny Shit in the Woods from , is��