This is the tenth year of my blog at , and since I started it, IÔÇÖve been fortunate to get to go on╠řsome pretty wonderful adventures. Throughout 2020, IÔÇÖll be writing about 12 of my favorites, one per month. This is the second in the series.

As we looked over our menus, we began to sense that the Waffle House staff was nearing a complete meltdown. It was evening, day 39 of our 49-day bicycle ride across America, March 15, 2010.╠řTony and I had pushed our bikes and trailers into a hotel room a block away, showered, and walked to the nearest restaurant, which was a Waffle House. We were tired and ready to eat. Almost six weeks into our trip, our bodies had basically turned into machines that pedaled fully loaded bicycles all day, burning 4,000 to 8,000 calories. WeÔÇÖd taken only three rest days so far╠řand would only take one more the remainder of the 3,000-mile trip, so our daily average was 66.67 miles. The day we arrived in Bayou La Batre, Alabama, we had pedaled 105 miles╠řfrom Rogers Lake, Mississippi. It was my first-ever century ride, and although Waffle House might not be many peopleÔÇÖs first choice after a ride like that, I was more than fine with it.

My back was to the open kitchen, so I could only eavesdrop, but Tony could see everything. From what we gathered, a rather large carryout order had come in, and the cook had totally fucked it up, causing delays with╠řnot only the large carryout order╠řbut all the orders for customers sitting in the dining area as well. Not to mention that the staff, arguing among╠řthemselves in full view, were╠řenough to convince even the most diehard Waffle House fan to eat elsewhere that night. Despite pleas from the waitstaff to call a manager in to help, the cook adamantly refused, making things awkward for everyone within earshotÔÇöwhich is to say the entire restaurant. It was the kind of thing that nowadays someone would record on a smartphone and post to Twitter in hopes that it would go viral. Since I couldnÔÇÖt see, Tony narrated for me, as we tried to calculate how much food to order to replace 105 milesÔÇÖ worth of calories.

ÔÇťThis is total mayhem.ÔÇŁ

ÔÇťThe cook just threw something.ÔÇŁ

ÔÇťOK, now the younger waitress is in the back crying.ÔÇŁ

Were we not touring cyclists, we might have╠řdecided to leave. But we just wanted to eat and go to bed so we could get up early and pedal 60-some miles the next day, and our dining options in such a small town were pretty limited, and further limited by the fact that, if we wanted to go to a different restaurant, weÔÇÖd have to walk to wherever it was. And,╠řyou know, you sort of have to ask yourself: If I want to go see America, is America things like the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon, and the Hollywood sign? Or is it a Waffle House in a small town, hoping that the staff doesnÔÇÖt mutiny╠řso we can get some hash browns? ThatÔÇÖs a rhetorical question, but IÔÇÖd argue for the Waffle House. ItÔÇÖs open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, a completely different scene at 2 A.M. than at 7:30 A.M., affordable to anyone who can scrounge up five bucks, and thus an option to people of all income levels but mostly patronized by those of us not in the 1╠řpercent. It╠řhas potential for brief moments of public theater, but it mostly just chugs╠řalong, making eggs and waffles. I mean, I love the Grand Canyon, but I think you can learn more about America at a diner.╠ř

We eventually were able to place our order, our food eventually came to the table, we eventually ate everything, and the Waffle House was still standing the next morning when we returned for breakfast, like nothing had happened. We ate pretty much the same thing as the night before, and a local sitting at the counter chatted us up, reminding us that part of Forrest Gump was set here, in Bayou La Batre, Benjamin Buford ÔÇťBubbaÔÇŁ BlueÔÇÖs hometown, where Forrest buys a boat to start the Bubba Gump Shrimp Company.

Tony and I went to high school in a town not much bigger than Bayou La Batre, and we spent many Friday and Saturday nights working together in a restaurant, washing dishes and busing tables. Tony shot up to six╠řfeet╠řten╠řinches╠řmidway through high school, and everyone expected him to play basketball, but he had other ideas. He topped out at seven feet tall, went to college, and became a chiropractor in Chicago╠řand an entrepreneur.

When he asked me in 2009 if IÔÇÖd like to bicycle across the country with him the next year, I said of course I would. He said heÔÇÖd pay for it, which was an ideal situation for me, since I was making $26,000 a year working at a nonprofit. IÔÇÖd been riding my steel road bike to and from work╠řin Denver for three and a half years, while trying to become an adventure writer╠řin my spare time. In Chicago, Tony had been getting into triathlons and road rides. The last time weÔÇÖd ridden our bikes any distance together was the last time I did RAGBRAI, the bike ride across Iowa, in 2000, and that was more of a party than a bike tour for us, to be honest.

Having not spent much time together in the previous╠řeight years, but hoping we could make it across the country on bikes and remain friends, we dipped our tires in the Pacific at Ocean Beach in San Diego on February 5, 2010, pushed our rides to the pavement, and started pedaling. Our final intended destination was Saint╠řAugustine, Florida, the opposite end of the ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Cycling AssociationÔÇÖs Southern Tier routeÔÇöthe flattest, shortest route across the country. Our first day, we climbed out of San Diego, managing 34.5 miles to Alpine, California.

Before I left for the trip, my wise friend Mick gave me two pieces of advice about long bike tours: ÔÇťYouÔÇÖre going to have some high highs and some low lows out thereÔÇŁ and ÔÇťDonÔÇÖt try to muscle through anythingÔÇöjust keep spinning.ÔÇŁ And my friend Maynard half-joked: ÔÇťI hope you like riding eight miles per hour into a headwind.ÔÇŁ All those things would ring true over╠řthe span of about 24 hours╠řmuch later down the road.

I didnÔÇÖt have any grand ideas about the trip, besides maybe being able to write about it for a magazine article or╠řeven a book.╠řI knew bicycling across America wasnÔÇÖt the most unique thing, but maybe something would happen that would sustain a narrative. I bought a URL╠řand created╠řa blog to keep our friends and families updated on our progress╠řand to help raise money for the nonprofit I worked for. I packed a $250 Asus laptop to try to keep the blog current╠řand added Wi-Fi service to my Verizon plan╠řso I could turn my flip phone into a hot spot when we werenÔÇÖt staying in a hotel with that capability.

I updated the blog every day, downloading photos from our digital cameras, writing a few sentences about our progress and╠řsometimes a quote from a conversation with a stranger. Most days, though, in the ÔÇťno shit, there I wasÔÇŁ sense of adventure writing, nothing really happened. What did happen is we plugged away, every day. We got up, ate as much food as we could stomach, got dressed, filled our water bottles, wheeled our bikes out to the road, swung a leg over the saddle, and started pedaling. WeÔÇÖd ride together for a few minutes, then╠řTony would get warmed up╠řand start to pull away, riding a half-mile, or a mile, or two miles ahead of me the entire day, stopping every couple hours to check in╠řor╠řstop at a caf├ę╠řto eat lunch╠řor pop into a convenience store to buy cans of Coke, Snickers bars, and whatever other calories looked good. Somewhere between 40 and 105 miles, weÔÇÖd╠řknock off for the day, find a hotel, shower, and eat at a restaurant. Tony wasnÔÇÖt that excited to camp, although weÔÇÖd brought camping gear (including a tent that could fit a seven-foot-tall person). I protested at first, saying I thought it would be ÔÇťmore legitÔÇŁ if we camped more. Tony said, ÔÇťRiding your bike across America is legit,ÔÇŁ and I could not argue with that point.

We rode across the bottom of California, occasionally looking at╠řthe U.S.-Mexico border fence to our right. We rode into Phoenix from the northwest╠řand out its╠řsoutheast side, almost 60 miles of pedaling to get across the entire urban spread, and we pedaled through the desert, away from angry dogs (I eventually developed a technique of explosively yelling at them, which stopped them in their tracks, surprisedÔÇöexcept for the rottweilers) and into New Mexico, where we hit the highest elevation of the trip, 8,228-foot Emory Pass, on day 15. We started to meet other cyclists on the same route, either headed in the same direction or the opposite way, and realized there was really no ÔÇťtypicalÔÇŁ cross-country rider: some were pedaling 50 or more miles a day, unsupported and stealth camping, while others were riding solo 20 or 30 miles a day, with a friend driving a minivan somewhere behind them. Some had a schedule, some were taking their time.

On day 20, we adjusted our route to take a less hilly path, avoiding the Davis Mountains in West Texas and heading to the town of Marfa on U.S. Route 90. My memory of the day is the flattest, straightest road IÔÇÖve ever ridden on, with a few barely noticeable adjustments to the left, a slight uphill grade the entire way, and wide-open ranchland along both sides of the pavement. In the morning, we caught up with a couple named Bruce and Dana, a pair of retired teachers from Tacoma, Washington, and rode with them a good part of the day. The chip-seal road was so rough that we tried to keep our wheels on the painted white line on the side of it, because it was that much smoother. Tony said he watched his bike computer slow from 14 to 9╠řmiles per hour╠řseveral times when he rolled off the white line. In 75 miles of riding that day, the only town weÔÇÖd pass╠řthrough on our map was Valentine, Texas, population 184, with no businesses to speak of aside from╠řthe post office. A few miles before Valentine, however, is the art installation , a fake Prada store in the middle of nowhere.╠řI was riding with Bruce and Dana, and Tony was ahead of us somewhere. We stopped, took some photos, and pedaled on, catching Tony in Valentine a few miles later. He hadnÔÇÖt stopped at the Prada store, because he hadnÔÇÖt even noticed it on the side of the road as he rolled pastÔÇöwhich is either almost unbelievable, because the ride was so straight-ahead monotonous, or completely expected, because the ride was so straight-ahead monotonous.

A few days later, I got the high highs and low lows Mick had promised. I did a lot of things to pass the time out there, pedaling six to eight hours a day, all the time in my own head while Tony rode a ways ahead. Tony had a little speaker on his bike to play music while he rode, but I didnÔÇÖt want to listen to music because I thought it would ruin my favorite tunes╠řfor me, spending all day listening to the same playlists╠řfor 300-plus╠řhours total by the end of the trip. So I chose silence, talking to cows as I passed, making up lyrics to songs, sometimes talking to myself a bit. I didnÔÇÖt have a bike computer or smartphone map, so I just pedaled, watching the horizon for signs of the next town. It was fantastically boring, and a decade later, when I spend all my waking hours checking my phone every few minutes, I look back on it with incredible nostalgia. I suppose we always look at the past as a simpler time,╠řno matter what, because we remember the images in our minds and the general tone of a memory╠řbut forget all the other things we were thinking about at the time. But it really did seem simple: wake up, eat, pedal, eat, pedal, eat, go to sleep, repeat until you hit an ocean.

On day 23, a few miles outside Langtry, TexasÔÇöunincorporated, population 12, home to a museum and almost nothing elseÔÇöI was pedaling by myself as the wind picked up, right in my face. I had read somewhere on the internet that you could camp in Langtry, but if you didnÔÇÖt arrive by 5 P.M., the water was shut off. So I was a little anxious to get there as the wind started pushing into my face, and then I began to get worried, because I had almost no water to drink, let alone to cook our food with when we camped that night. Then I got a flat tire. And the wind picked up some more. Then I got another flat tire. I got very frustrated╠řand then just kind of lost it for a few seconds. I screamed at the top of my lungs for a couple of minutes╠řwhile pedaling by myself╠řinto the wind, alone on a highway, cranking my metaphorical steam valve wide open, and then, catching my breath, closing it again. Low, low: check.╠ř

When I arrived in Langtry, the rumor about water turned out to be false. I bought and ate a few╠řice cream sandwiches at the corner store. We set up the tent, had╠řdinner, crashed, and during the night, the wind picked up to a steady 30 miles per hour, coming from the east. The next morning, we headed out╠řwith a handful of candy bars from the museum store to sustain us to Del Rio, 55 miles away. We pedaled, looking like two cartoon characters leaning into the wind, in granny gear on the uphills╠řand granny gear on the downhills, too. I just laughed╠řand kept spinning. The wind wouldnÔÇÖt let up╠řor even change direction. If weÔÇÖd had╠řmore food with us, we might have stopped for the night, but we didnÔÇÖt, so our only hope was to reach Del Rio. We pedaled for 11 hours, stopping once at a small bar to grab some bags of potato chips and a few candy bars. We averaged five╠řmiles per hour the entire way, the wind never relenting until our last five miles into town╠řin the dark. Pedaling eight╠řmiles per hour into a headwind, as Maynard had said, would have been a dream.

We rolled our bikes into a hotel room in Del Rio, ordered three large pizzas from DominoÔÇÖs, ate them, and went to bed. Later that year, Tony would finish his first Ironman Triathlon, and when I texted him to congratulate him, he texted back that it wasnÔÇÖt nearly as bad as ÔÇťthat day in Texas with the headwind.ÔÇŁ

One of the things I believe many people will tell you about a long trip, whether itÔÇÖs thru-hiking a long-distance trail, backpacking a hostel circuit for a month and a half, or pedaling a bicycle for weeks at a time, is that itÔÇÖs as much about the people you meet as it is about the places you see. You meet people on a bike tour because you are on a bike, and the bicycle is a conversation starter. People see you as somewhere between a little crazy and a complete idiot╠řbecause youÔÇÖve chosen╠řto travel by bicycle in the 21st century╠řbut also, because of the bicycle, they╠řfind you probably harmless enough that you wonÔÇÖt mind a little chitchat. If they see you and your fully loaded bicycle outside a restaurant, convenience store, or hotel somewhere, they will ask you some, if not all, of these four questions:

- Where are you headed?

- Where did you start?

- How many miles do you ride every day?

- What do you eat?

At some point in the conversation, youÔÇÖll get a chance to ask them, ÔÇťAre you from around here?ÔÇŁ and in that way, you get to meet a few people. Which is something that happens way less when youÔÇÖre traveling inside a gas-powered, climate-controlled vehicle, in my experience. On my bike, I had brief conversations with Walmart greeters, waitstaff, ferry employees, convenience-store clerks, and fellow restaurant patrons, and it helped new, strange places feel welcoming, wherever we were.

The thing I started to feel as we racked up the miles, and that we both agreed on years later, is that we were going a little too fast╠řand that maybe it would have been nice to have taken a little more time and do a little more exploring╠řand talking to people. At the time, though, TonyÔÇÖs business was young, and he was definitely motivated to get back to work and try╠řto keep things moving forward from the road with spotty cell service. And I was just grateful to have two months off work (even unpaid), something that hasnÔÇÖt happened since and may not happen again in my life. As we made our way across Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and finally╠řFlorida, we ran into more and more people bicycling the Southern Tier╠řand even one lady, Robin, riding the Southern Tier as just one leg of a giant rectangle around the perimeter of the United States, ensuring sheÔÇÖd still be pedaling her bike after IÔÇÖd been back in the office for six months.╠ř

We had friends join us for sections, including our pal Nick╠řfrom high school, who rode the last 210 miles with us from Tallahassee to Saint Augustine, slipping in as seamlessly as if heÔÇÖd ridden the previous 2,800 miles. As we got closer to the end, I started to think about what weÔÇÖd done╠řand how I framed it in my life. I couldnÔÇÖt really nail it down. It felt like a big adventure, but in the Yvon Chouinard╠řsense of ÔÇťwhen everything goes wrong, thatÔÇÖs when adventure startsÔÇŁ never really happened;╠řweÔÇÖd made it through pretty unscathed and according to plan, aside from a bunch of flat tires and a couple of worn-out bike chains. It went really wellÔÇöbasically the opposite of a book like Into Thin Air, when everything did go wrong, to the point where it became a disaster and a bunch of people died. In 49 days together, we didnÔÇÖt even have enough disagreements to fill half an episode of The╠řReal Housewives of New Jersey.

In the ten years since Tony and I started pedaling east from San Diego, IÔÇÖve been lucky to spend lots of time in the outdoors, doing a bunch of different things that fall under the idea of adventure. Be it backpacking, rock climbing, mountaineering, backcountry skiing, trail running, kayaking, whitewater rafting, or bikepacking, I think about all of it as travel╠řand trying╠řto understand something through a mode of travel. Because whether itÔÇÖs a boulder problem or a 2,200-mile thru-hike, you define it as╠řmoving╠řfrom one place to another by human-powered means, crimping through a 12-foot-tall V11╠řor walking three╠řmiles per hour for 250 miles, from starting line to finish line or put-in to take-out. On our bike ride across America, I realized that traveling by bicycle is just about my favorite way to see a place: slow enough to take in scenery╠řbut with the ability to coast, carrying everything I need with me╠řbut not on my back, and burning enough calories to eat a large pizza every evening if I want to.

IÔÇÖve since become friends with a couple of people who also bicycled across the U.S.╠řbut arenÔÇÖt from here, one Chinese and the other English. I sometimes wonder how different their trips were from mine, how different their perspective was on it, and if any of us (or anyone really) can say theyÔÇÖve actually ÔÇťseen America,ÔÇŁ because America is a story╠řor an idea, and itÔÇÖs much different now than when I pedaled across it in 2010. I guess all I know is that if you want to put in the effort, and you want to feel like youÔÇÖve seen it, I donÔÇÖt know a better way than on a two-wheeled machine that runs on Snickers bars and diner coffee. I canÔÇÖt say exactly where you should go to look for America; I can just say IÔÇÖd look somewhere besides the internet.

I never did try to write a book about our trip. I did manage a couple of magazine articles╠řand a few blogs about bike touring, and I left our blog up on the internet for a decade before I finally made it private. But as the ten-year mark approached, I wanted to do something to thank Tony for the trip. So I started copying and pasting all the text from all those blogs, and tracking down all the photos, and cringing at some of my writing (and fashion choices) at the time.

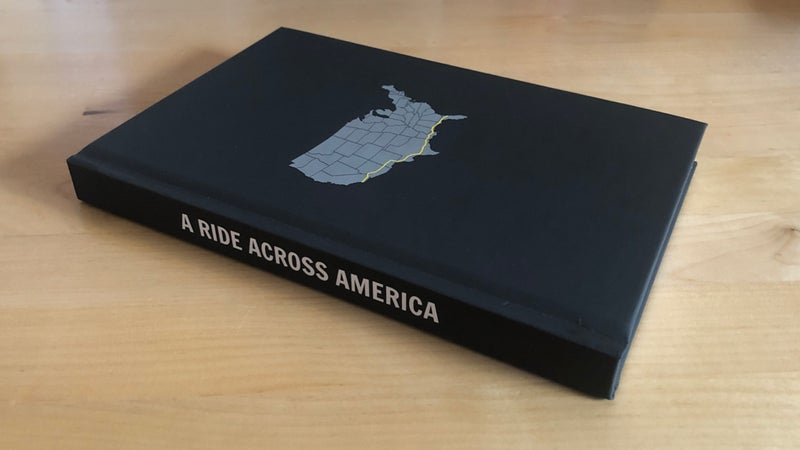

I spent probably 25 or 30 hours formatting everything╠řinto a hardcover book. I printed a total of three copiesÔÇöone for Tony, one for me, and one for my parents (my dad had printed╠řand kept all the blog posts in a file this whole time). The photography isnÔÇÖt amazing, and IÔÇÖm not particularly proud of the writing, but itÔÇÖs a book.

I finished it and had it ready to ship to Tony a few days late for the tenth╠řanniversary of the start of our trip, and I composed╠řa few sentences on a card to stick in the package. I canÔÇÖt remember the exact words I wrote, except for two things: ÔÇťThanksÔÇŁ and ÔÇťstill one of the biggest and best adventures of my life.ÔÇŁ