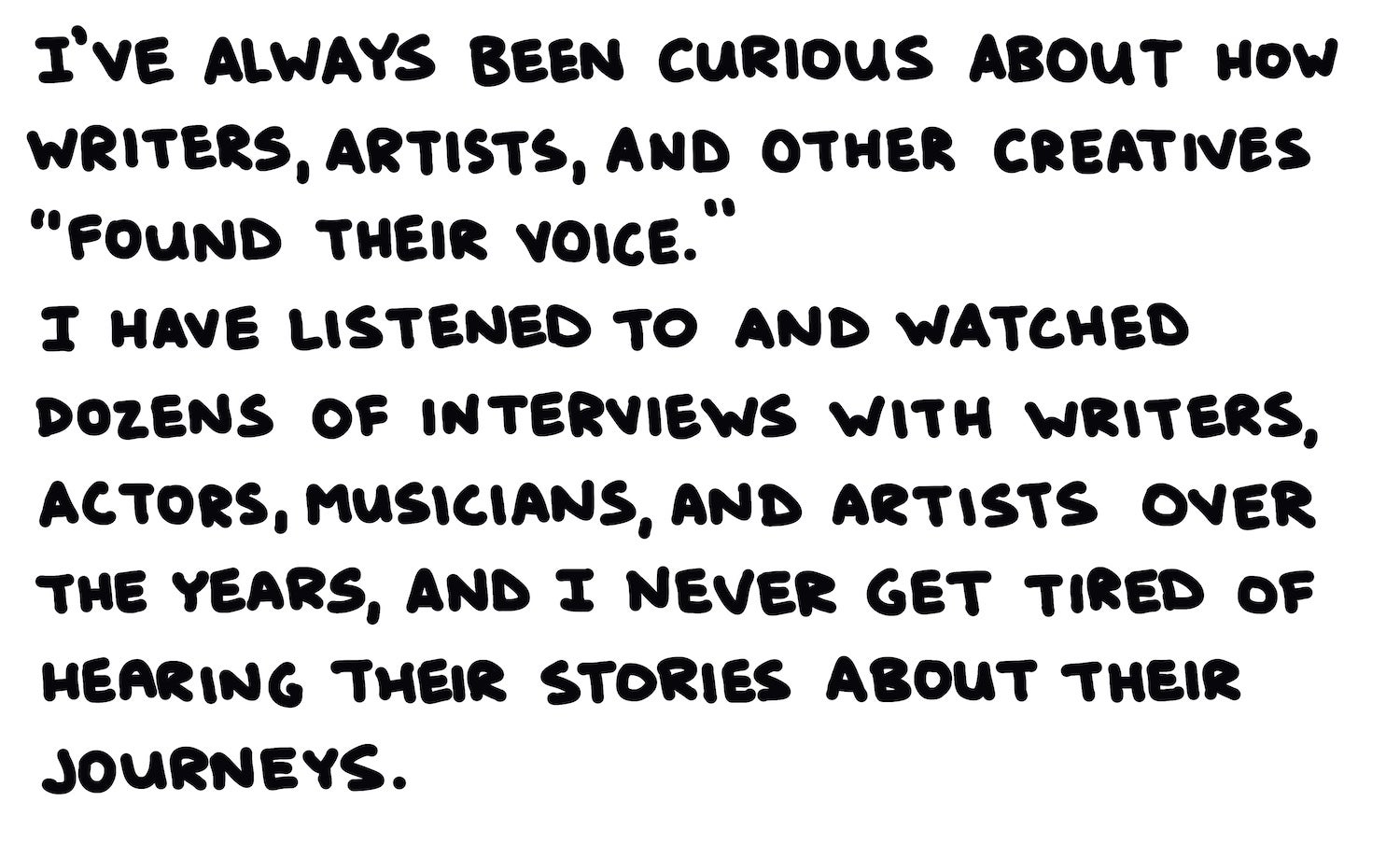

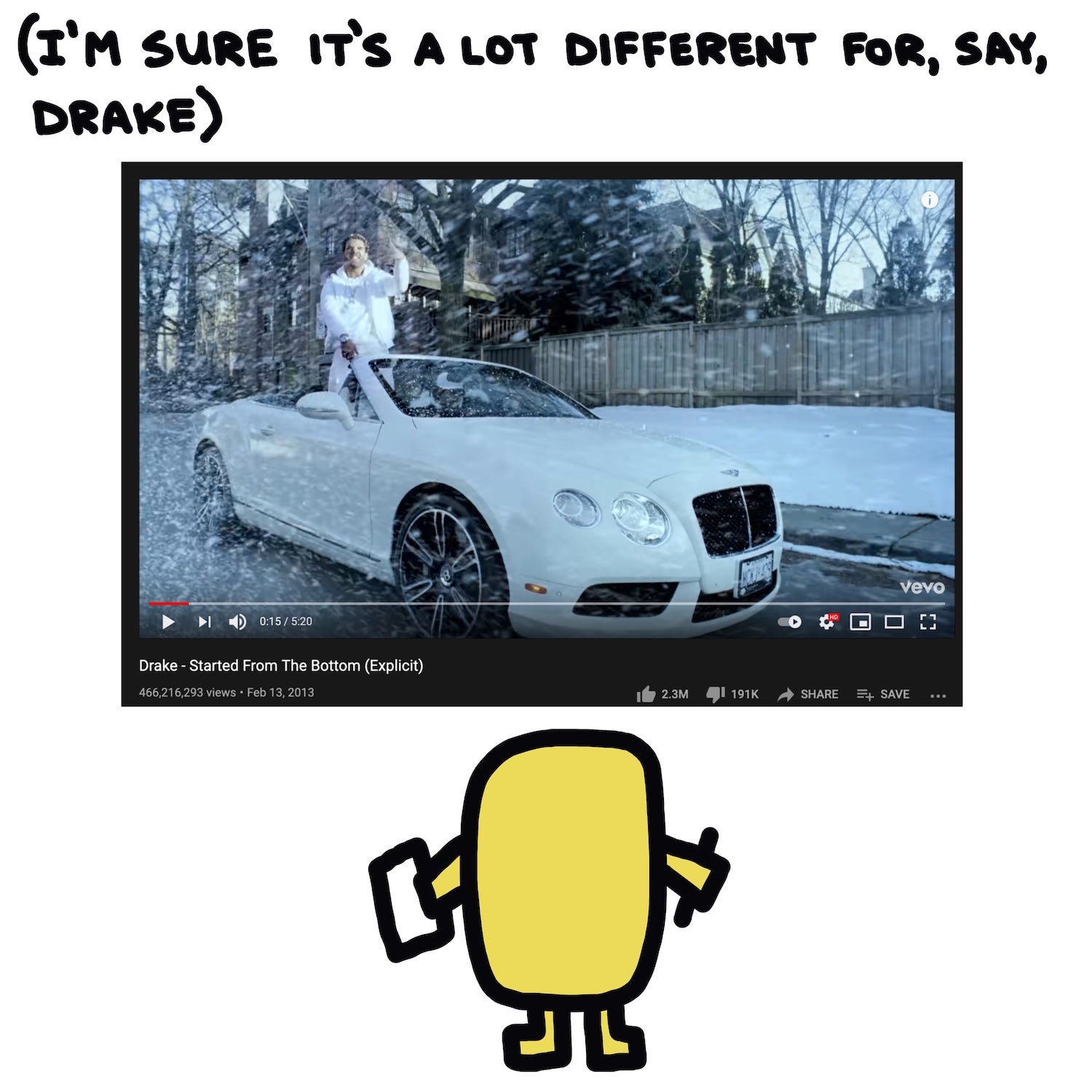

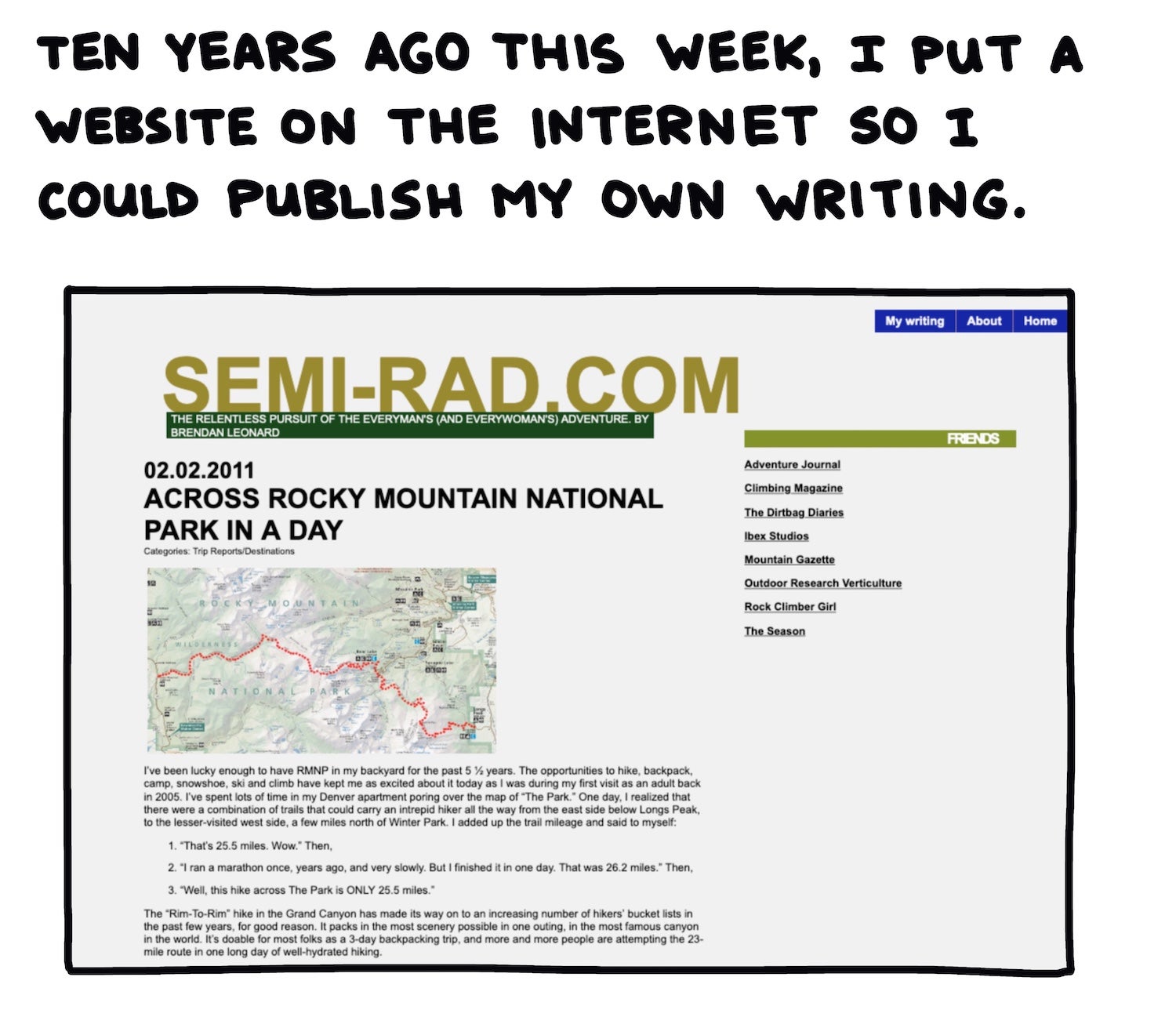

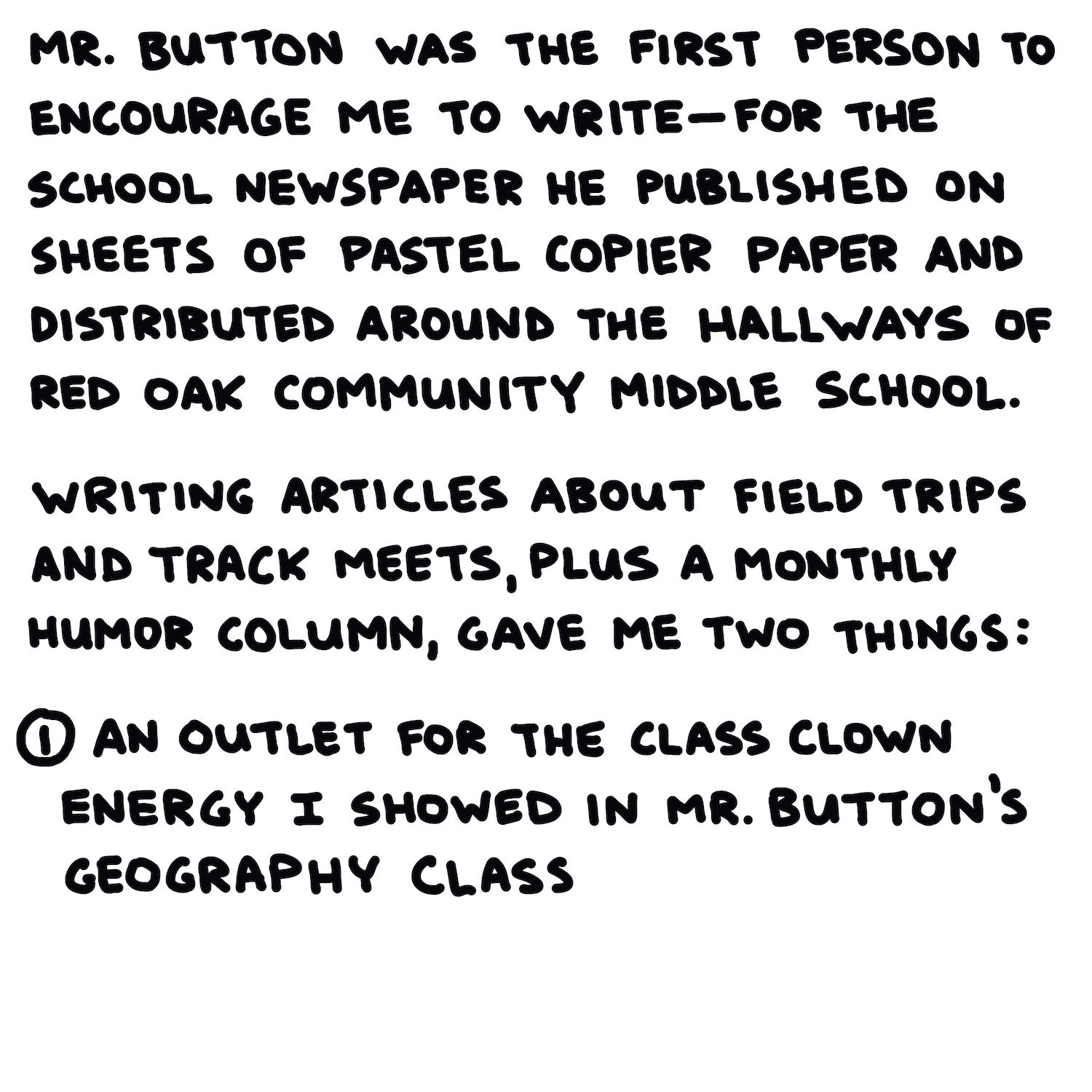

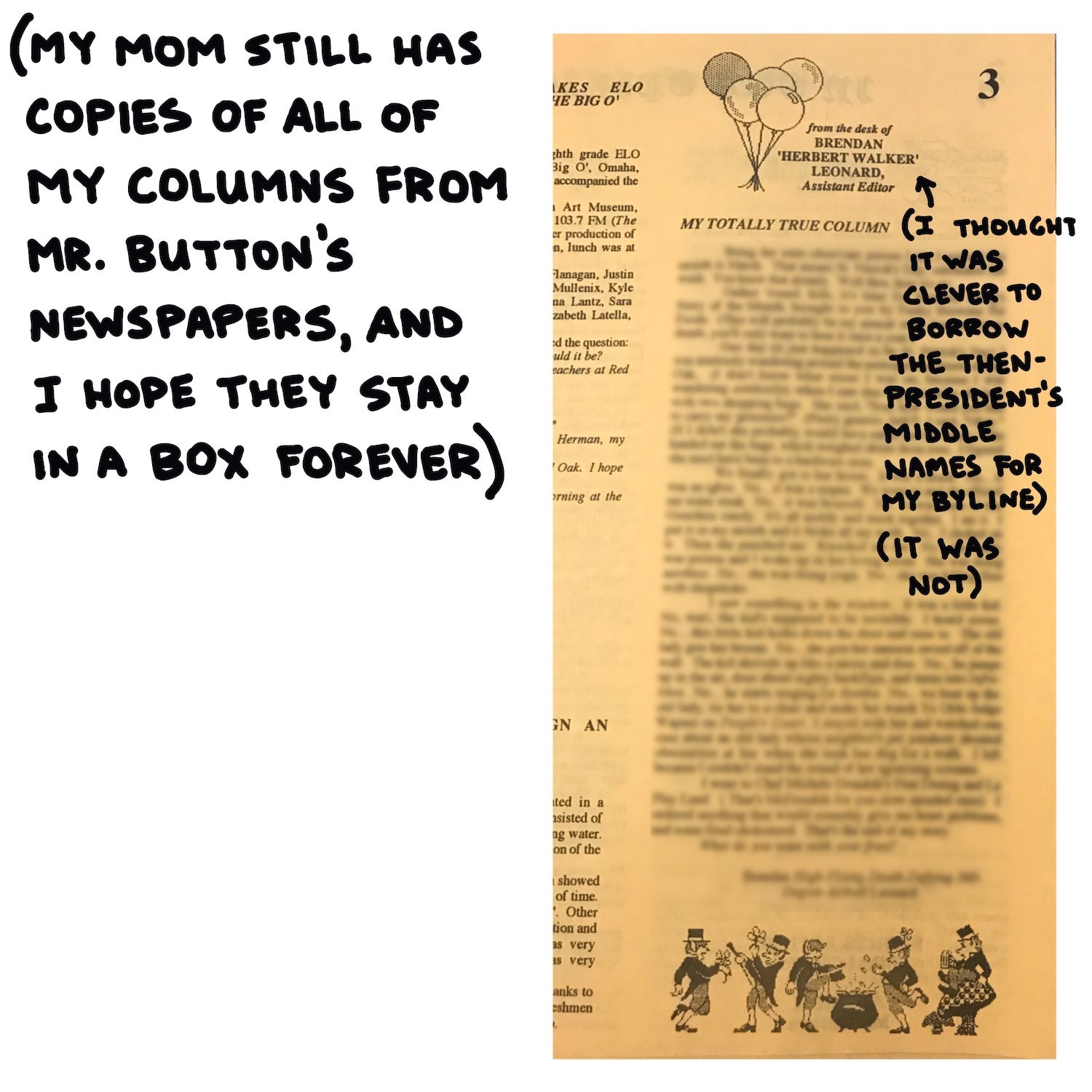

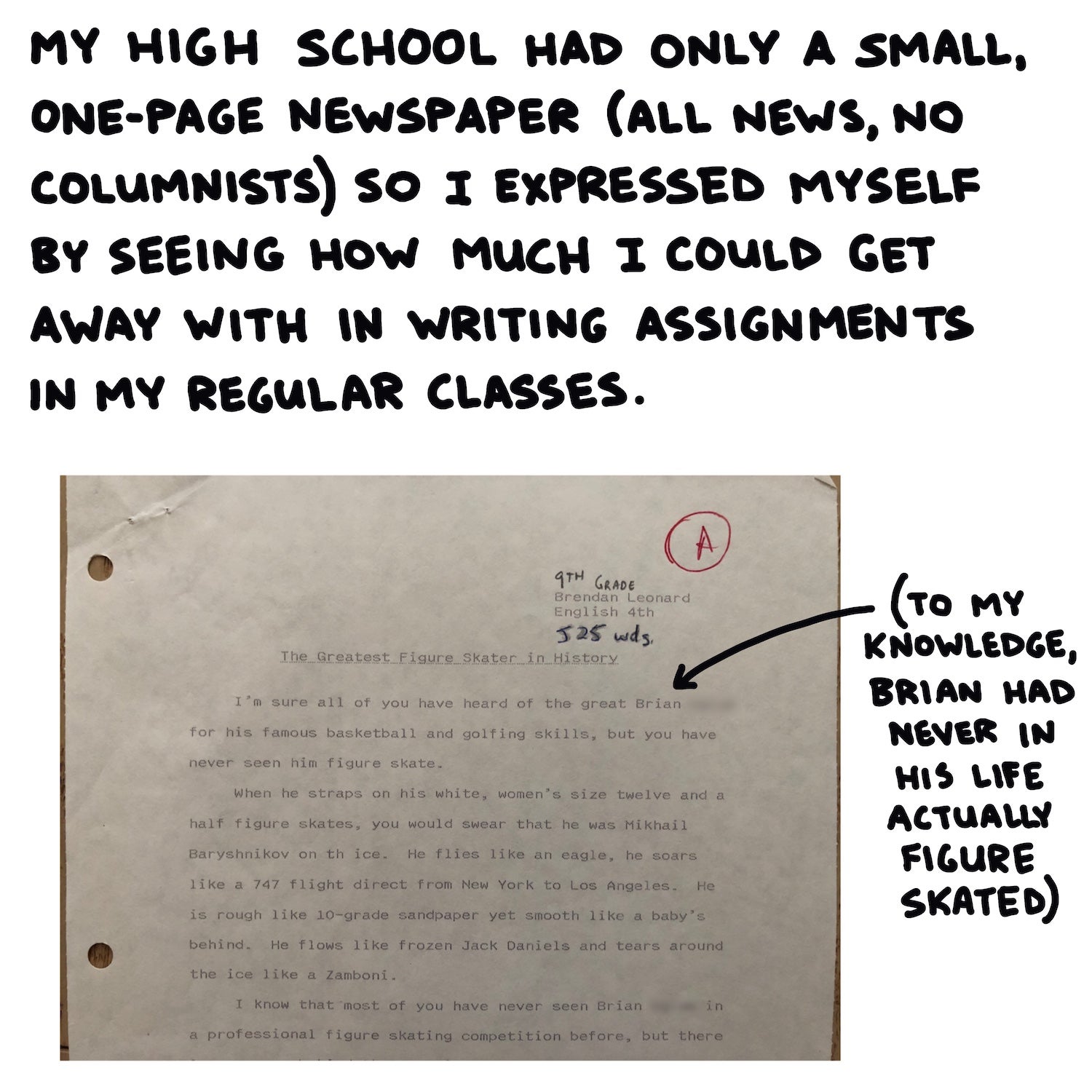

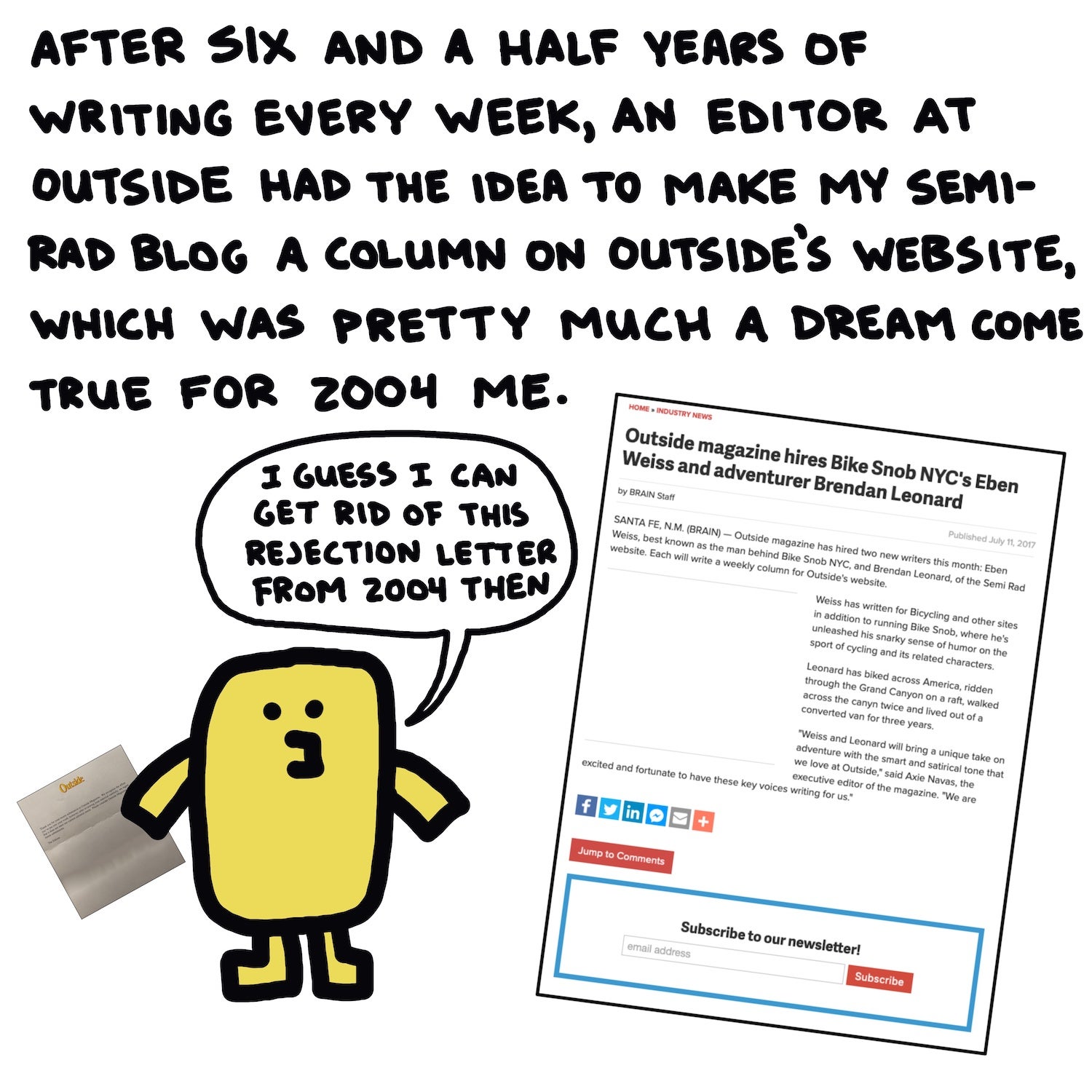

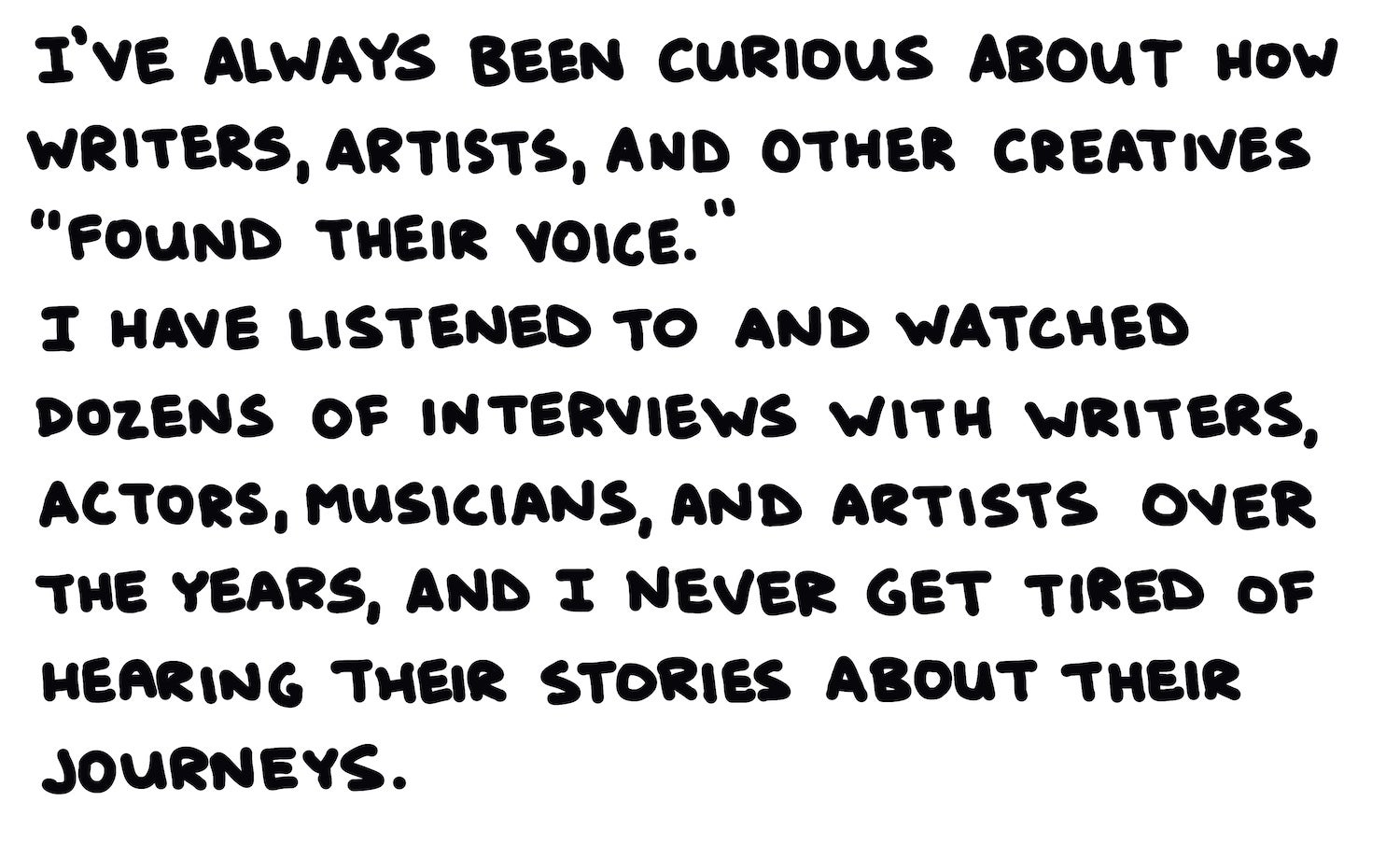

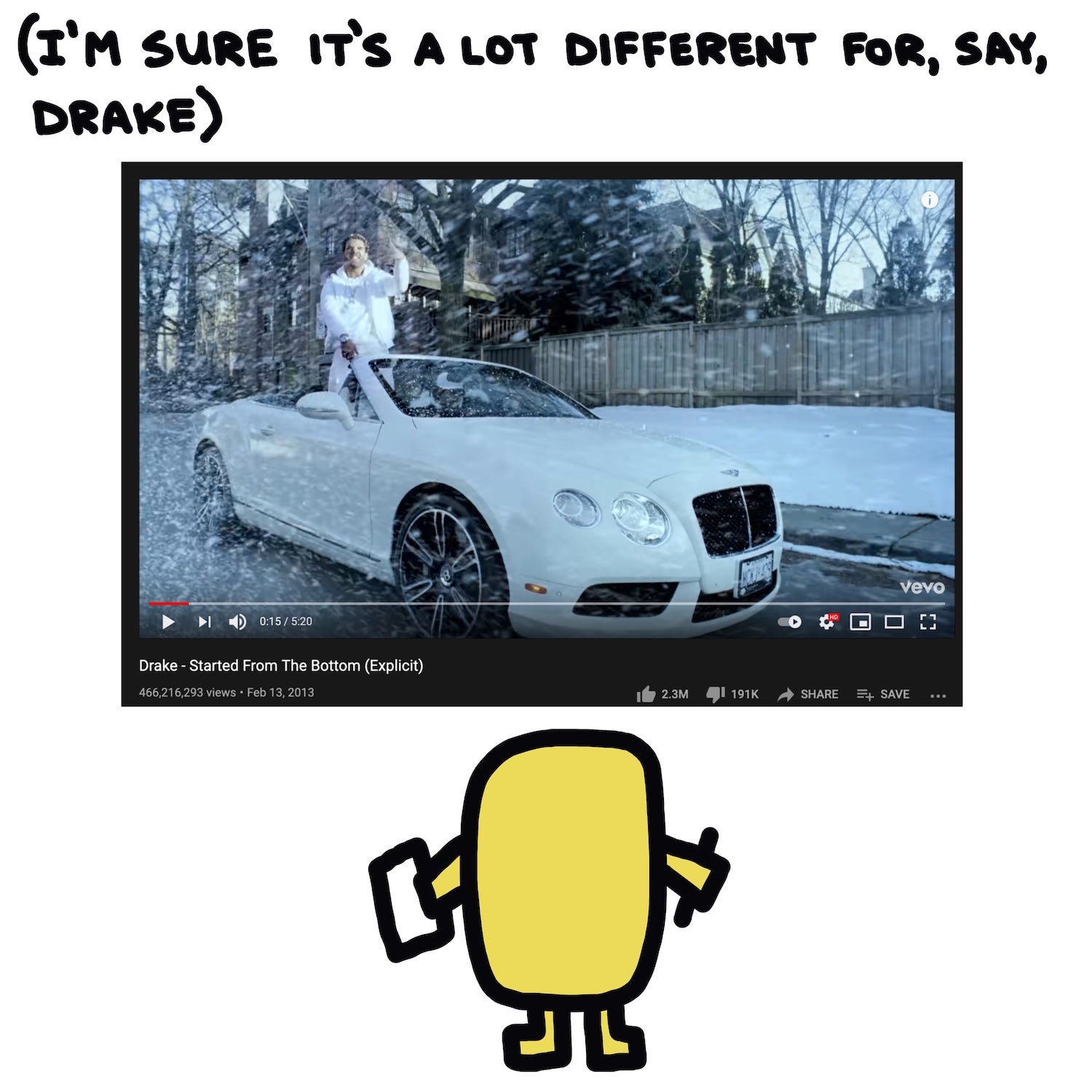

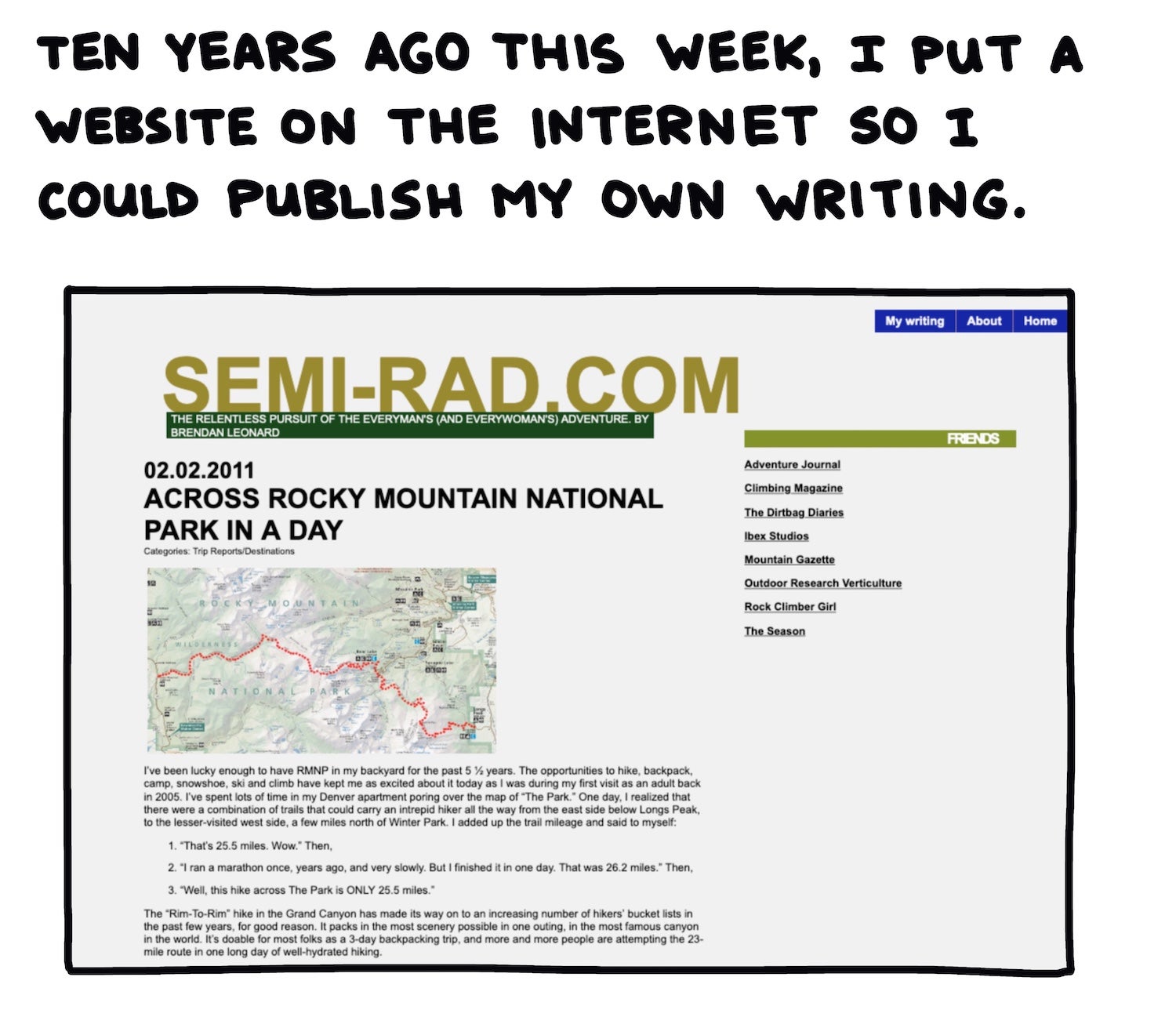

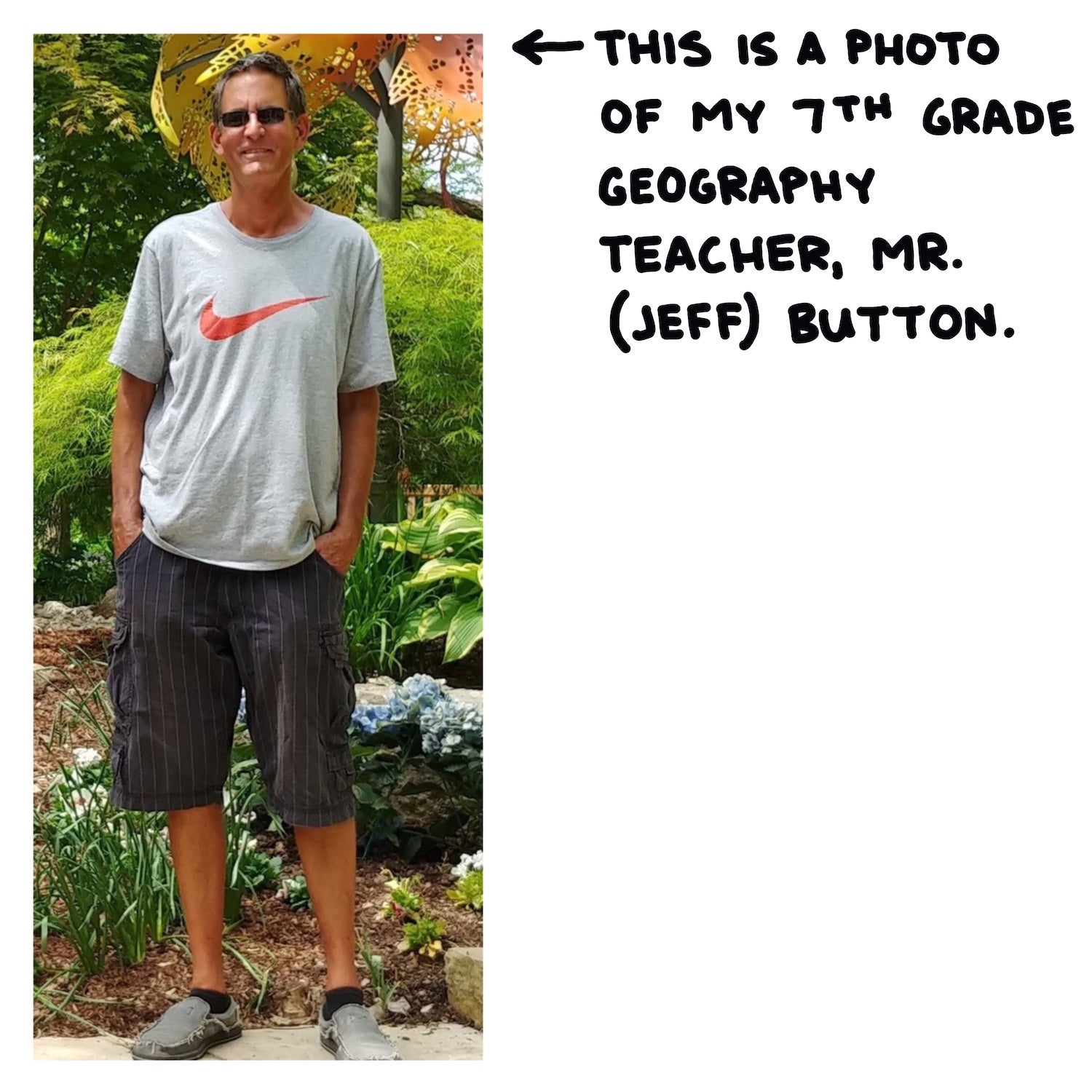

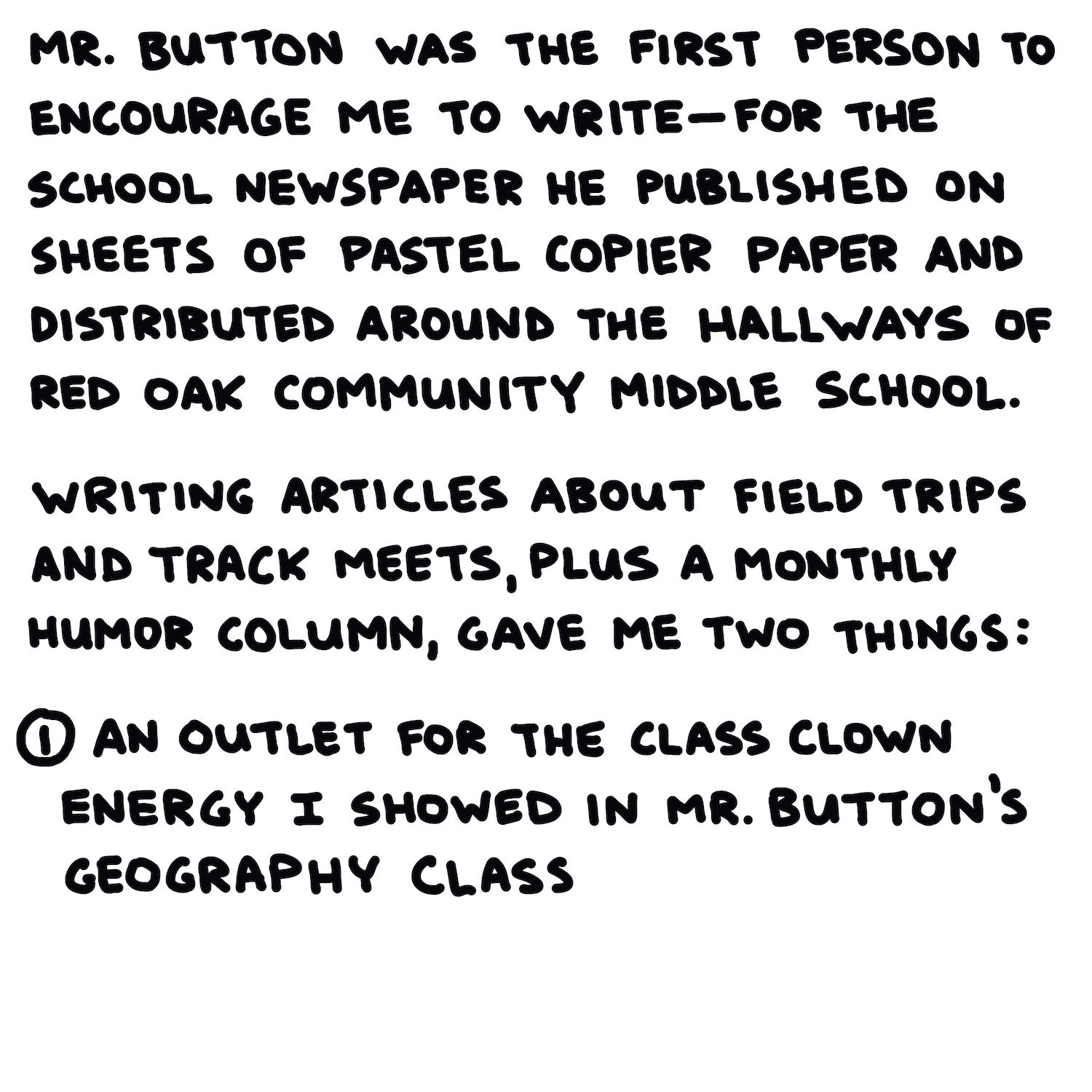

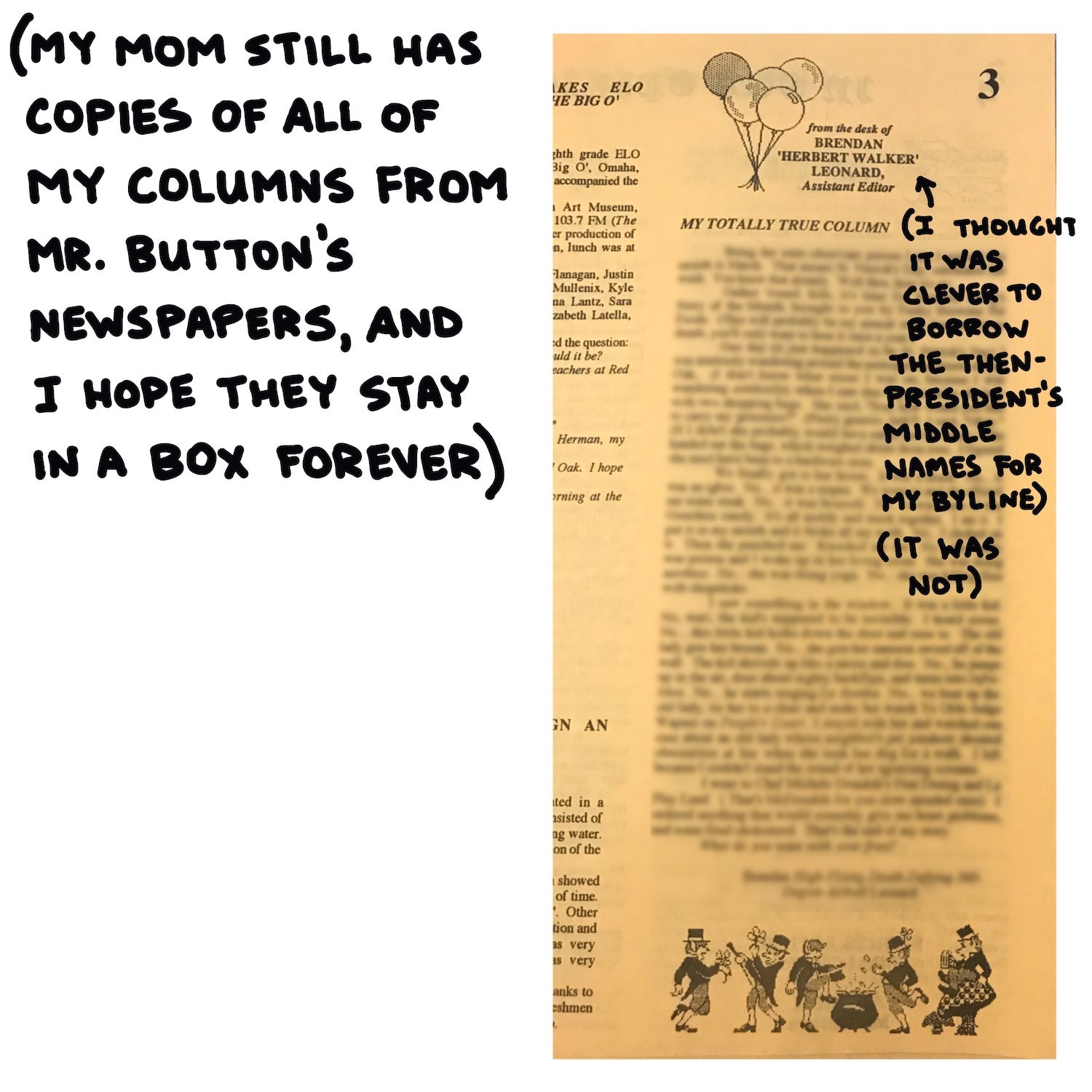

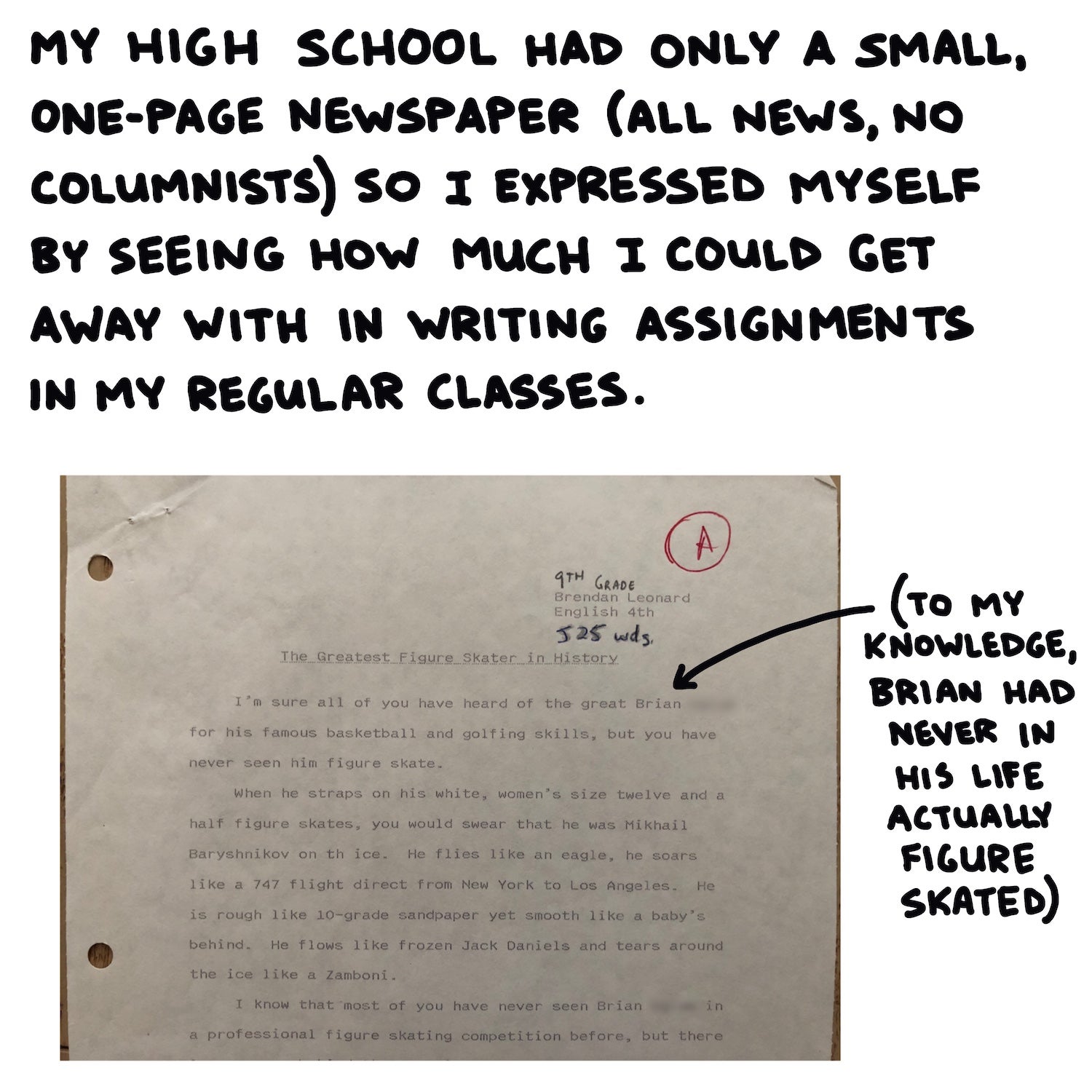

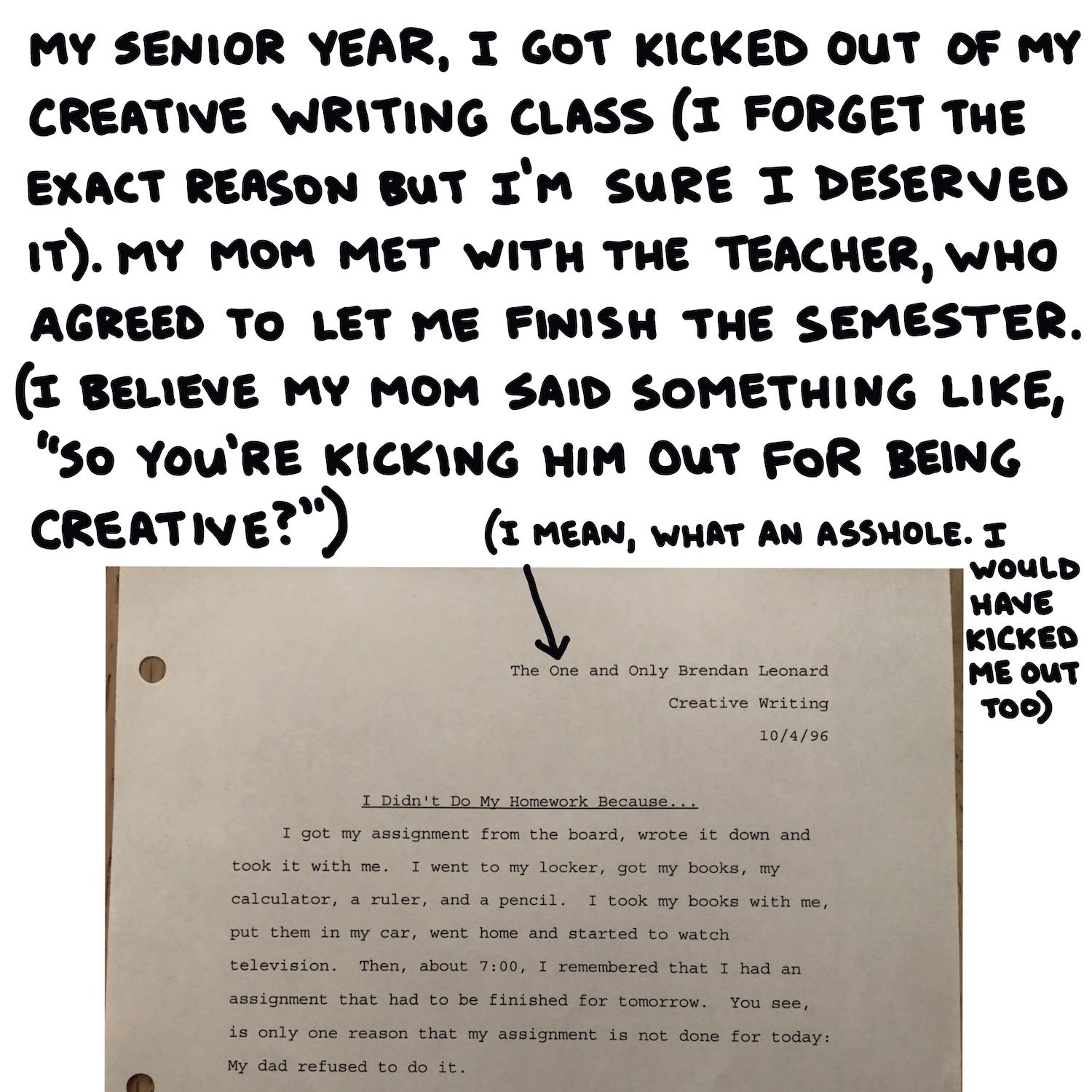

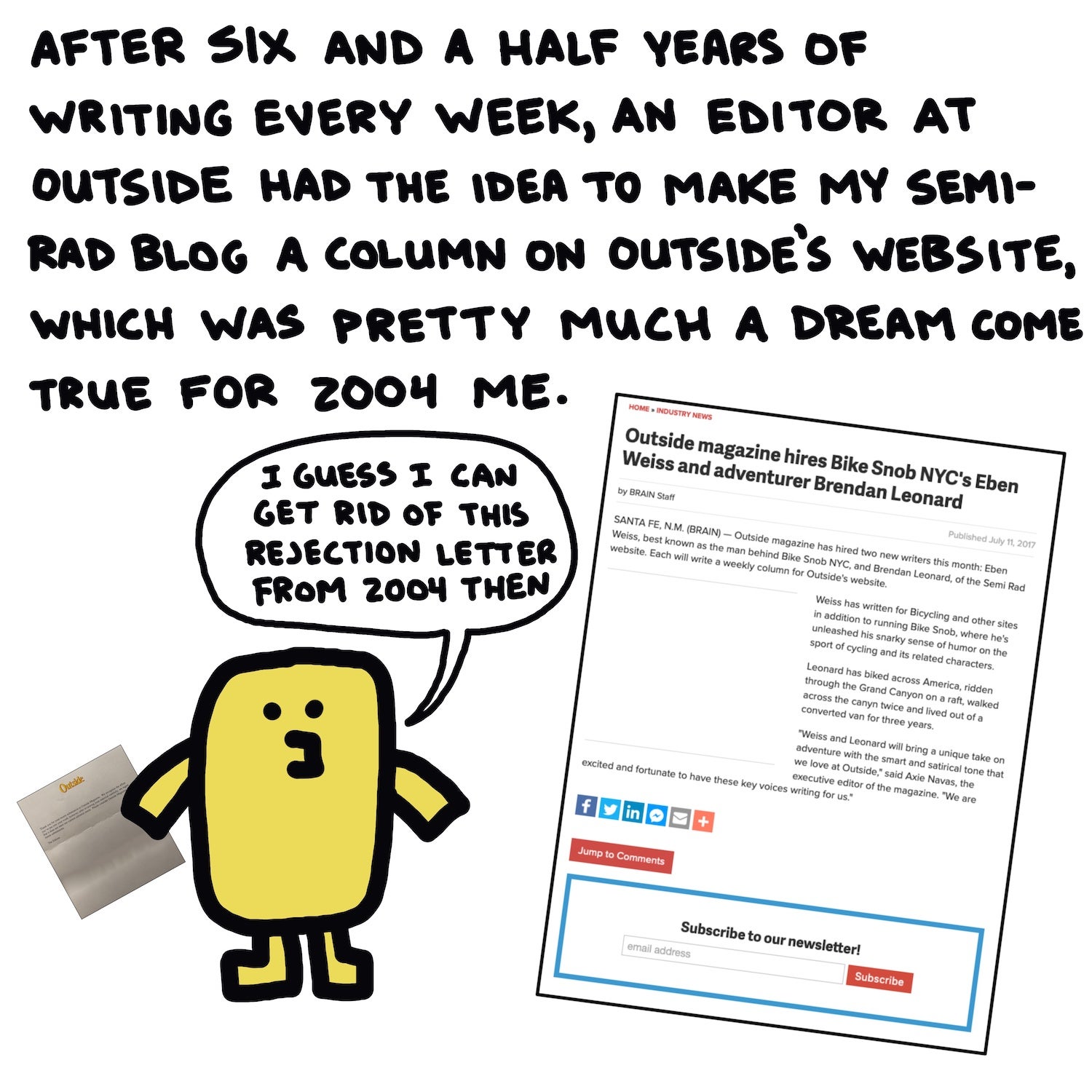

![(2) A creative extracurricular[1] activity, something that would resurface as a creative āside gigā in college and be a constant in my adult life. [1] when campaigning for āpresidentā in Mr. Buttonās class (just a class exercise, not āclass presidentā), I subjected the class to five minutes of campaign promises that I rapped over the instrumental of āO.P.P.,ā an awkward stunt that was probably an example of the type of thing that made Mr. Button think that I had enough time on my hands for some writing](https://cdn.outsideonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/04/finding_a_voice_10.jpg)

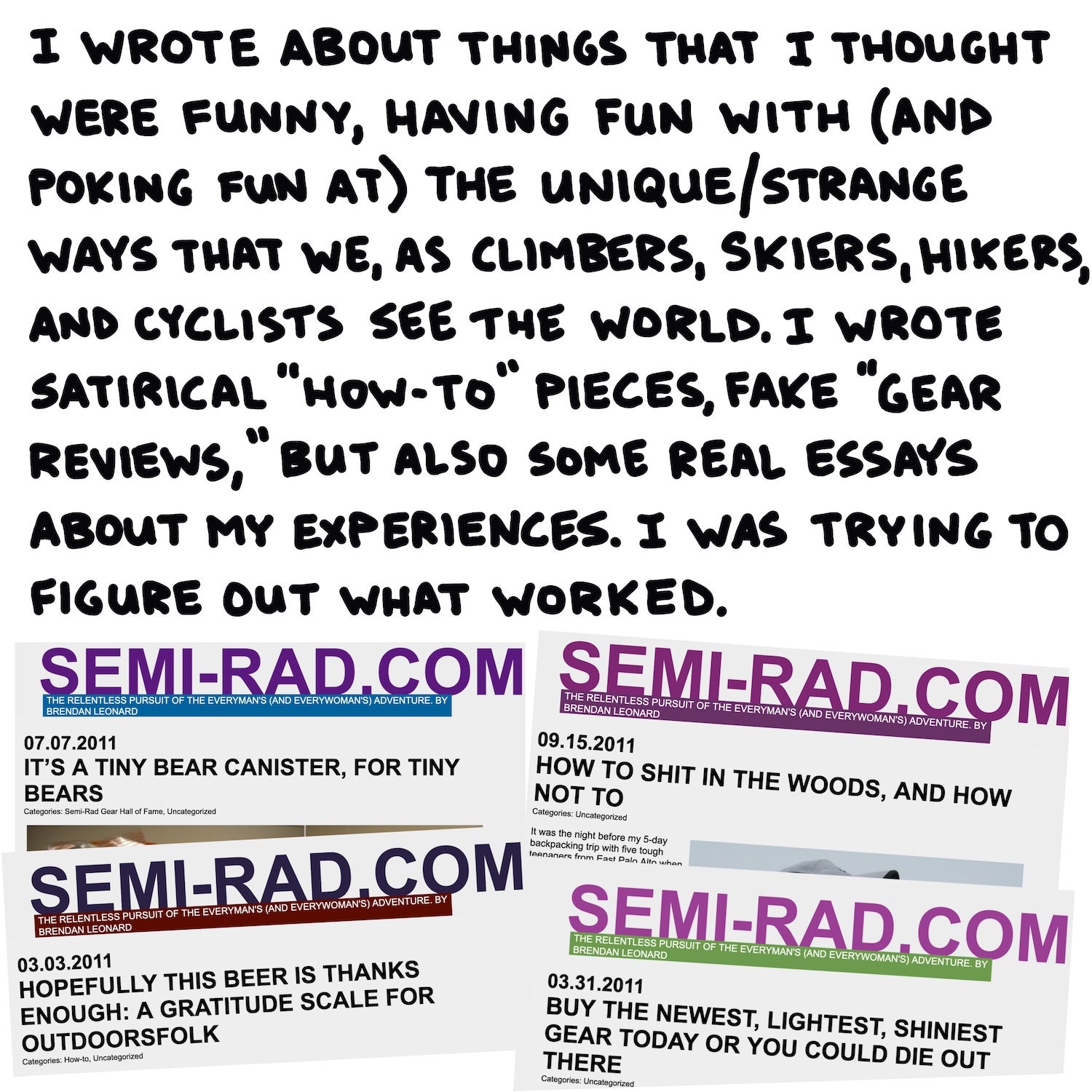

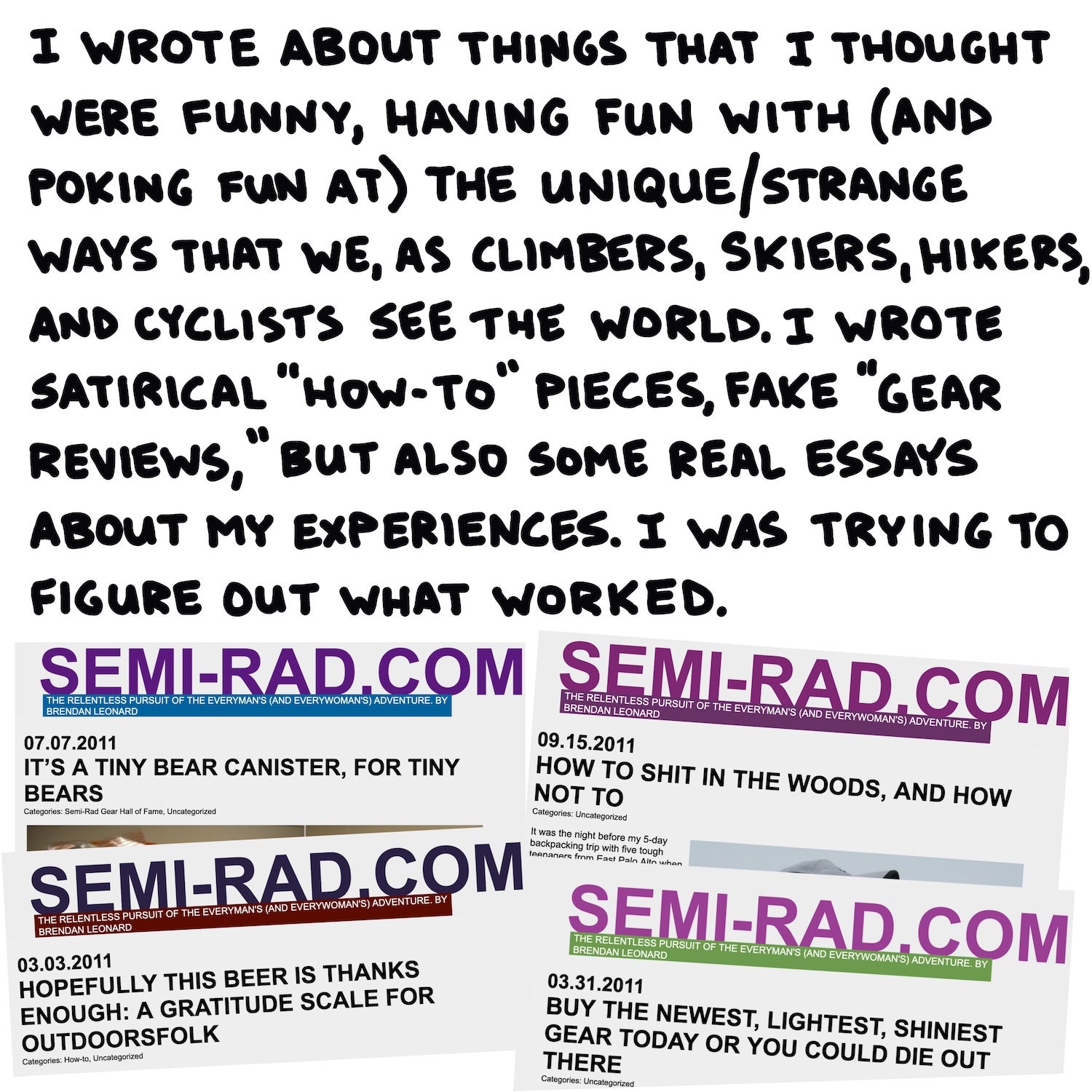

Brendan Leonardās new book,Ā , is now available for preorder.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

![(2) A creative extracurricular[1] activity, something that would resurface as a creative āside gigā in college and be a constant in my adult life. [1] when campaigning for āpresidentā in Mr. Buttonās class (just a class exercise, not āclass presidentā), I subjected the class to five minutes of campaign promises that I rapped over the instrumental of āO.P.P.,ā an awkward stunt that was probably an example of the type of thing that made Mr. Button think that I had enough time on my hands for some writing](https://cdn.outsideonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/04/finding_a_voice_10.jpg)

Brendan Leonardās new book,Ā , is now available for preorder.