“Dreamland” sits high on a rocky outcrop in the middle of the Juneau Icefield, not far from the border between Alaska and British Columbia. It’s a corrugated metal box—a two-stall outhouse with a little wooden flag that you can prop up while using the facilities—and it has a view more than worthy of its name.

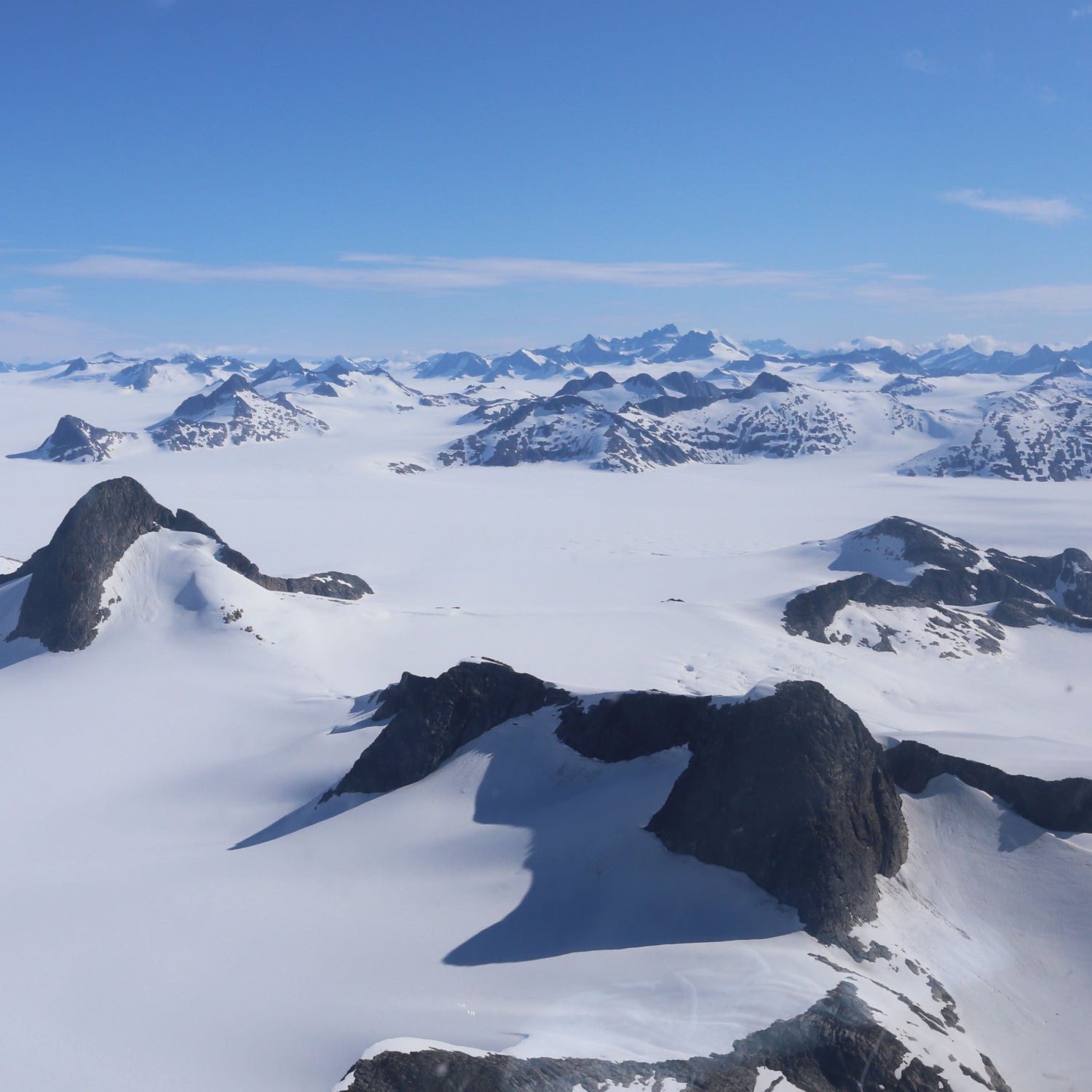

Through the weather-beaten windows, the lucky occupant can behold the vast, white expanse of Taku Glacier. The ice flows relentlessly downhill like a colossal river, but here, the glacier looks more like an ocean, lapping against the shins of distant peaks and filling the chasm that would otherwise yawn before them. Dreamland and the other buildings that make up Camp 10 rise above its frozen shores, perched on an island of granite.

I came to know Taku well as a student in the Juneau Icefield Research Program in 2005. I spent much of that summer digging snow pits all over the upper reaches of the glacier, which sprawls across nearly 300 square miles of ice-sharpened mountains. In the span of a few months, our team of a half-dozen college kids moved hundreds of tons of wet, heavy snow, sometimes excavating holes more than 15 feet deep.

The goal—aside from getting a good workout—was to document the past winter’s accumulation. When weighed against the glacier’s annual ice loss, it would tell scientists whether Taku was growing or shrinking. And for decades, Taku’s ample snowfall allowed it to keep advancing in spite of climate change. Many described it as “defiant.” I found it comforting.

Climate change is too often marginalized as a problem afflicting only far-flung, frozen corners of the planet. It’s . But I happen to love cold places, with their infinite textures of ice, the chiaroscuro of snow on rock, and the grandeur of desolation. As warming mercilessly assailed them, I clung to the knowledge that the glacier I knew best remained the exception.

Taku wasn’t just holding out. It was gaining ground.

Taku Glacier is named after the T’aaḵú Ḵwáan people, whose name in Tlingit means “flood of geese.” The phrase likely refers to a time, memorialized in oral history and geologic evidence, when the glacier was even larger than it is now and dammed the Taku River, forming a great lake that attracted waterfowl.

The lake last drained in the 1700s, when Taku Glacier started to retreat. But in the late 1800s, a strange thing happened. While other glaciers in the region continued to shrink, Taku stopped in its tracks and began advancing again. For much of the following century, the most pressing question about Taku was: How big would it get?

By the 1900s, the glacier had become a major tourist attraction. Cruise ships would anchor close to the terminus—a towering cliff of ice—and blow their horns to make icebergs shatter into the sea. And by the 1980s, Taku had grown enough to prompt new concerns about another ice dam, which would disrupt valuable salmon fisheries and cut off access to promising mining prospects.

But Roman Motyka, a geophysicist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, knew that Taku was on borrowed time. Southeast Alaska has warmed dramatically over the last several decades, driving nearly every other glacier into retreat and making Taku even more of an outlier. “Climate was eventually going to catch up,” Motyka says.

Taku endured so long because it has several advantages, including its geometry. A large fraction of its surface area sits at elevations high enough for snow to survive the summer. And historically, abundant snowfall more than compensated for whatever ice melted down low, buffering the glacier against rising temperatures.

Glaciers that empty into the ocean also march to a different beat than glaciers based entirely on land. So-called tidewater glaciers like Taku often bulldoze a mound of sediment ahead of them as they grind down a fjord. When perched on this mound, called a moraine, tidewater glaciers flow more slowly and calve fewer icebergs, which allows them to advance even in unfavorable climates. In effect, these moraines serve as anchors in times of change.

Despite these defenses, climate change has finally come for Taku. In 2013, the glacier , and sometime between 2015 and 2018—no one knows exactly when—it began to retreat. Scientists that they now expect Taku to start receding up its fjord, perhaps very quickly. Once a glacier backs off its moraine and becomes free floating, it can collapse catastrophically. The Columbia Glacier in Alaska’s Prince William Sound has lost .

Chris McNeil, a geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage, remembers the day he realized that Taku’s retreat had begun. He was sitting in his office, skimming satellite images of the glacier, when he spotted a patch of water between Taku’s snout and its terminal moraine. “The term ‘blows your hair back’ kind of comes to mind,” he says. “It just kind of took us all by surprise.” (Like me, McNeil became smitten with Taku as a student on the icefield in 2009.)

Mauri Pelto, a glaciologist at Nichols College who has studied Taku for decades, put it more bluntly. “Of the 250 glaciers I have personally worked on it is the last one to retreat,” Pelto wrote . “That makes the score climate change 250, alpine glaciers 0.”

When I read the news, I can’t say I was shocked. But a new sadness—a cold emptiness—bled across my memories of Taku. I’m a trained geologist and a journalist who writes about climate change, and I know what warming does to glaciers. I knew Taku owed its “defiance” to physics, not willpower. But I hoped it might prevail all the same.

It’s an example of an increasingly familiar kind of cognitive dissonance: I understand that the world is changing, but I do not believe that this riotous meadow, this palatial forest—this beloved glacier—will change. I accept the story of climate change, but I resist the devastating details. The natural places that have defined my life serve as my anchors. If I lose them, what’s to stop me too from collapsing?

In 2017, I returned to the Juneau Icefield Research Program to teach science communication. As the helicopter thundered toward Camp 10, I imagined traversing Taku’s sun-cupped sea and admiring its splendor—preferably from the peace and quiet of Dreamland. It would be a few more years before anyone knew that Taku had already begun to retreat, and I did not suspect it. When I arrived, the glacier still looked immense and invincible.

No one knows what will happen now. One possibility is that Taku will go the way of the Columbia Glacier. If that happens, it could wither in my lifetime. Collapsing tidewater glaciers often recede until they hit shallow water. And like many, Taku carved out its fjord as it advanced, digging its own grave.

In such a scenario, McNeil says, the ice could disappear as far upstream as Camp 10, which currently sits more than 15 miles from the terminus. The ice there is more than half a mile deep (Taku is among the thickest mountain glaciers in the world) and I struggle to imagine it gone. “It would be comparable to standing on top of El Cap and looking down at the bottom of Yosemite Valley,” McNeil says. Dreamland would sit not on a frozen shore, but on the brink of an abyss.

However, there’s also a possibility that Taku will retreat more gradually. Its terminal moraine—low and wide, dotted with lupine and horsetail—blocks warm seawater from melting the ice from below, McNeil explains. As long as the moraine survives, it will remain a bulwark, potentially stretching Taku’s retreat over centuries instead of decades. Perhaps not all glaciers behave like Columbia. Perhaps Taku will continue to fill the windows of Dreamland for generations to come.

Motyka, for his part, still holds out hope that the terminus is just shifting around like he’s seen it do before, and that the glacier isn’t really retreating at all. “It probably is,” he admits, “but 10 percent of me is saying, ‘well, we’ll see what happens.’”

Every place, every community, every person affected by warming faces a similar reckoning. Change is coming, but how much? What will we lose? What will be left? Uncertainty hounds us, impervious to hope.

The future depends largely on what we do next. Scientists agree that acting quickly to halt climate change will limit its damage. But our fate also hinges on factors outside our control: how sensitive is the climate system to human disruption? What tipping points lie ahead—and have we unknowingly crossed some already? Has collapse begun, or will the bulwarks hold?

At Taku, McNeil and his fellow scientists are keen to document what unfolds as a force of nature reverses course. I take this as a lesson, telling myself that observation is also a way of living with change. The future remains inscrutable and largely unwritten. But if love is paying attention, then our job is to keep watch. Even when it breaks our hearts.