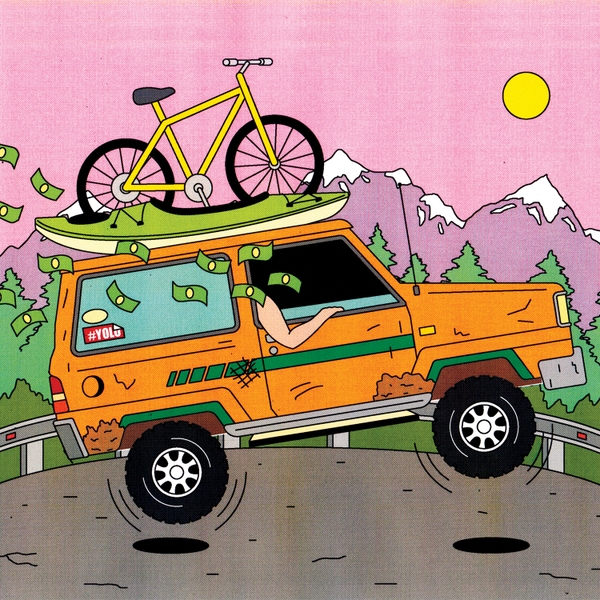

Young, Dumb, and Broke: Why Outdoorsy Types Suck at Money

It’s not just the gear purchases—it’s how we think about the future. Here’s the ���ϳԹ��� guide to getting your financial $hit together, no selling out required.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

When I was in my twenties, I did something very bad. I made about $290,000 disappear.

What that number represents is the majority of the six-figure salary and bonuses, after taxes, that I earned over the five years I worked in financial services. When I say that I made it disappear, I don’t mean that I lost it day-trading shares of Pets.com. I frittered it away, gradually, methodically, paycheck by paycheck. I was living in San Francisco, and the details are fuzzy (in no small part because I was often drunk during those years), but I can tell you that there were $60 rounds of drinks purchased without a second thought and $25 cab rides to the bars. There were $1,500 ski-season cabin shares in Lake Tahoe and a $150-a-month membership at Equinox. There were multiple Starbucks lattes per day and $18 organic steak salads eaten at my desk. But these are just the flashes through the fog, clues to an unpleasant memory I’ve blocked out. Because when I think too hard about the truth, it hurts my head: I have no idea where all my money went.

I did eventually learn to curtail the spending. When I was 27, I quit my job to travel and ski-bum, and by that point I had managed to save a small sum that could float me for a year. I called it my fuck-you money, because if I was ever in a situation I didn’t like—stuck in a job or with a boyfriend I wanted to leave—I could say fuck you and go. Living in ski towns is how I learned the dirtbag lifestyle, and to my surprise I took to it naturally and with enthusiasm. My savings sat untouched, and I survived off the wages I made operating chairlifts in Queenstown, New Zealand, and serving barbecue in Aspen, Colorado. I ate peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for breakfast and free staff meals for lunch. I stopped drinking for a while, snowboarded every day, and spent almost nothing. I was happy.

Embrace Your Inner Dirtbag

Personal-finance guru Mr. Money Mustache breaks down how ���ϳԹ��� readers can stop wasting our hard-earned cash on expensive gear and trips and start putting it toward real freedom: the financial kindWhen I went back to work, I chose outdoor journalism, placing myself at the intersection of two industries that would never make me rich. I lived frugally; my first job paid $42,000 a year. But as my salary grew, I ratcheted up my lifestyle to meet it. I never lived that extravagantly again, nor did I save much. My spending habits were an incongruent mishmash. I’d camp instead of pay for a hotel, and I wore the same puffy jacket forever, patching holes with duct tape. Yet I rarely thought twice about eating out or buying a new mountain bike every year.

My parents tried to talk to me about investing, but I’d roll my eyes and groan like a child. I didn’t want to be rich; I wanted to be happy. Talking about index funds felt beneath the enlightened alternative lifestyle I aspired to. I wasn’t interested in buying a house either, because a down payment would eat up all the fuck-you money, and then I wouldn’t be able to quit my job to travel or freelance or ski again. So the money sat in a savings account for years, losing roughly 3 percent of its purchasing power annually. By the time I was 34, the single most valuable asset I owned was my carbon mountain bike. Fuck me.