What Should Happen to Drivers Who Kill Cyclists?

The family of Lauren Davis desperately sought answers after she was fatally struck by a driver while biking to work in New York City in 2016. At every step, the criminal-justice system let them down, raising the question of what justice should look like for victims of traffic violence.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On April 16, 2016, Danielle Davis stepped off an overnight flight from San Diego to New York City with her mother, Lana. The morning before, Danielle’s older sister, Lauren, had been killed by a driver while riding her bike to her job at the Pratt Institute, an art and design school in Brooklyn. She had just turned 34. Lana had the address of a police station, the location of the crash site, and nothing else.

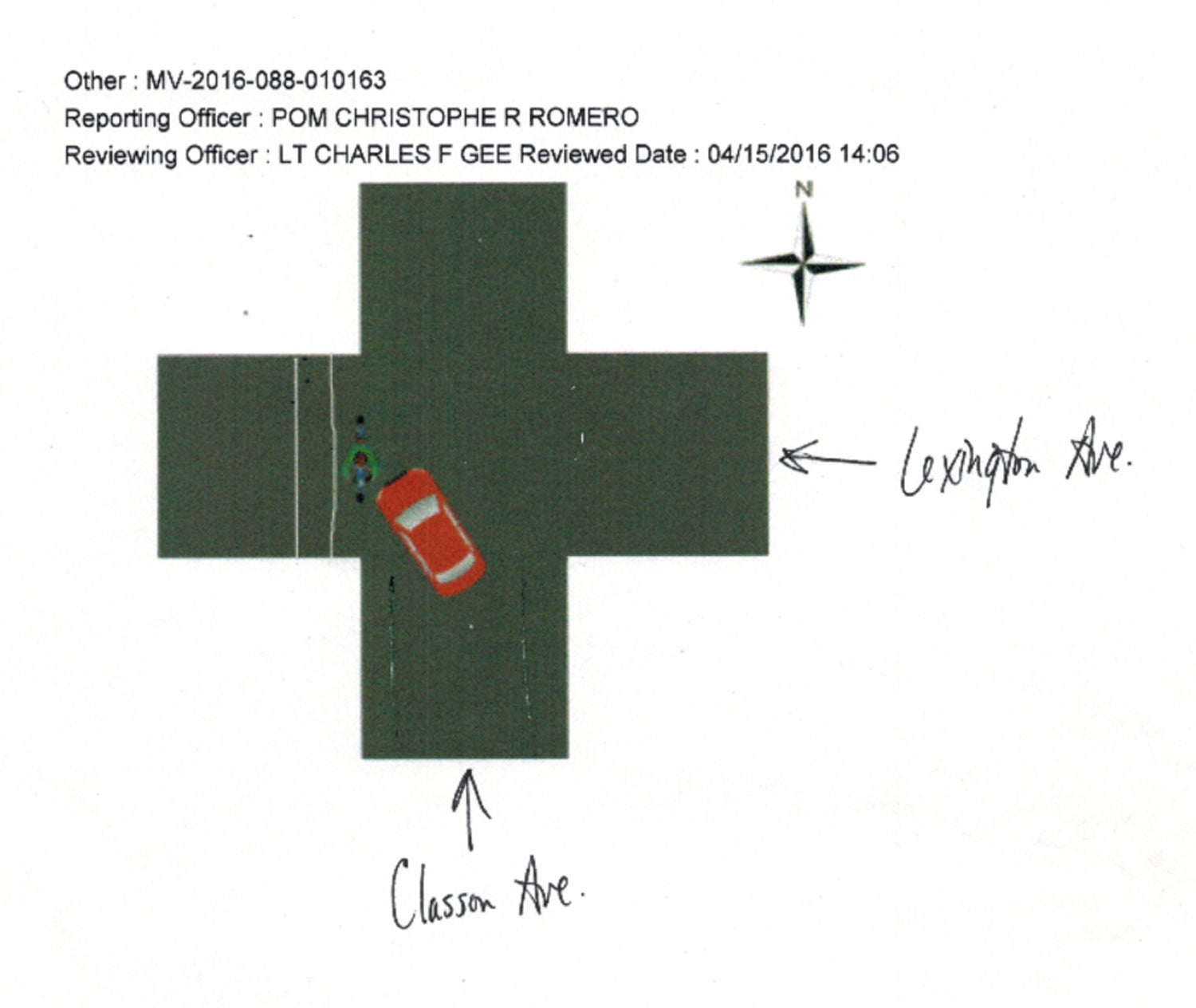

Danielle and Lana went to the site of the crash, on the corner of Classon Avenue and Lexington Avenue in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill neighborhood. A streak of Lauren’s blood was on the cement, next to a broken pair of sunglasses. “When you’re grieving, you’re just looking for signs that she’s still around, that this person has not completely disappeared,” Danielle says.

Later that morning, one of Lauren’s friends drove them to the New York City Police Department (NYPD)’s Collision Investigation Squad (CIS) headquarters in Brooklyn, where they met an officer named Christophe Paul, who was in charge of the case. “He told us that she was ‘salmoning’—biking against traffic—south, instead of north, to her place of work,” says Danielle. The NYPD , too.

In the notebook that Danielle kept at the time, she wrote, “The car bumps Lauren, she falls off the bike, they’re unsure how.” Paul handed them a copy of a crash report that said the same, but he told them the final copy he was writing could change if more information came to light during the investigation.

From the police station, Danielle and Lana went to the medical examiner’s office in Brooklyn to identify Lauren. In life, Danielle says, her sister had been the brave one. “She wouldn’t take no for an answer,” Danielle told me. She was “a self-described goth” and had spent the previous few months studying the way the Dutch masters symbolized death in their paintings. “Lauren really encouraged me to go outside and explore—to not feel afraid,” Danielle says. But now all of that was gone. Her face was smashed beyond recognition, her skin swollen and bruised. “She was an amazingly beautiful person,” Danielle says, “and the crash just tore all of that away from her. Not only her life, but whatever semblance of who she was. She wasn’t there.” They ultimately identified Lauren by a tattoo of an Egyptian ankh on her back instead.

Danielle, now 36, describes this day as a series of fragmented scenes, full of surreal decisions. “You want to know: What happened, where’s Lauren, why isn’t she alive? And suddenly you’re asked, ‘Which organs do you want to donate?’” She tried to make sense of the passing time by keeping fastidious notes. “I documented everything, every single day—what we did, where we went, what happened. I think it was just because I didn’t believe it myself.”

Back at Lauren’s apartment, Danielle and her mother agreed that there was a disconnect between what they’d seen at the medical examiner’s office and the detective’s account of the crash. “There was this one quote that made me really start to doubt him,” Danielle told me. “He said he doesn’t believe that she made contact with the car.” The medical examiner told them that Lauren had likely been run over—the car had left a smear of red paint across her helmet. (When asked about these initial discrepancies in Paul’s account of what happened, the NYPD responded, “When the NYPD’s Collision Investigation Squad responds to a collision, a preliminary investigation is conducted based on available evidence. However, the investigation is ongoing and is subject to change as additional evidence is gathered and documented over the coming weeks and months.”)

The next morning, Danielle and Lana decided to go back to the scene of the crash to set up a memorial and to see if they could figure out more about Lauren’s death on their own. “We were told that videos would disappear from local businesses within a week,” says Danielle. “So we had seven days to hunt down witnesses, videos, whatever evidence we could to help Officer Paul do his job.”

They staked out the corner where Lauren was hit, figuring they might meet someone who had seen the crash on their regular commute. Lana says she flagged down sanitation workers and anyone passing by who might have been nearby that morning. Danielle stood by the spray of blue and yellow flowers they placed on the sidewalk and solicited people as they walked past: “My sister was killed here on Friday, do you know anything?” Danielle describes herself as the more reserved of the two sisters, but stopping strangers on the street felt natural, she says. “It just felt like what Lauren would have done for me.”

A woman in scrubs told Lana that she’d been walking past on her way to work at a hospital and had held Lauren in the road after the crash. Others told them about being hit by drivers on nearby streets. “My mom and I were so desperate to find answers that, even though it was traumatic to hear, it felt like piecing together the puzzle,” Danielle says.

Three days later, they found what they were after. A woman in a red bike helmet rode past the memorial. “She looked at us from the other side of the street,” Danielle recalls. “And then she rolled up and asked us, ‘Is she OK?’”

They’d soon learn that the police did have it wrong. “Watching a person who’d been made a victim be erased, almost consumed by an institution that was supposed to serve and protect her, it felt like a betrayal,” Danielle says. “It just felt like humanity let us down that day.”