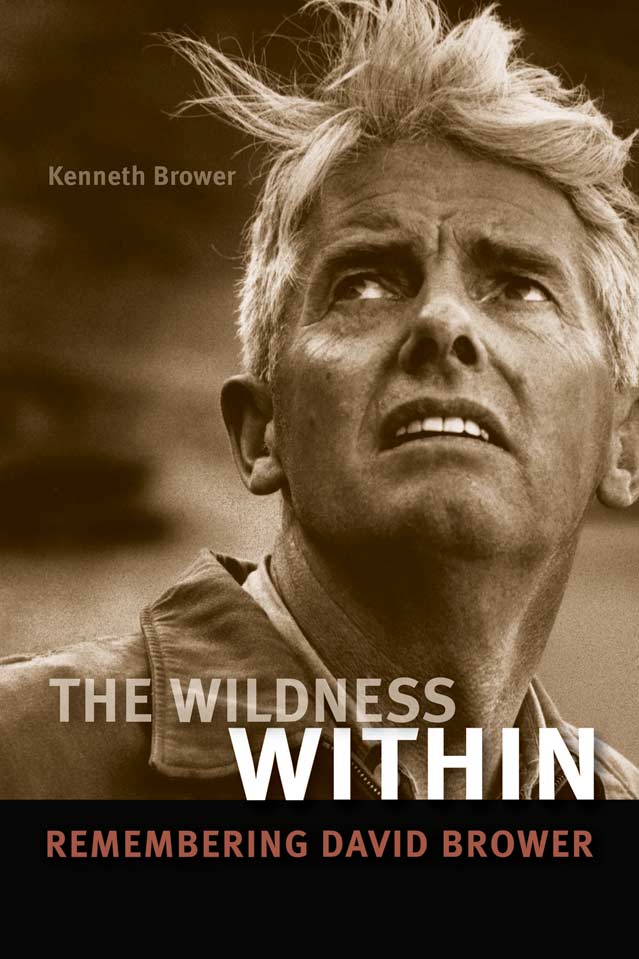

David Brower became the godfather of the modern environmental movement when he joined the Sierra Club in 1952 and grew it from a hiking fraternity to the most powerful conservation outfit in the U.S. before the board of directors booted him out two decades later. Some called him the second coming of John Muir. Others called him a selfish preservationist who hampered progress and profit. All agreed that he was an immovable force of nature to be reckoned with. In his time, Brower founded half a dozen conservation organizations and helped establish another half dozen national parks and seashores, made films, published books, bagged a slew of first ascents as an elite climber in , and was nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize. , published in May, is writer and environmentalist Kenneth Brower’s tribute to his father a century after his birth. The author talked to ���ϳԹ��� about his father’s legacy, the problem with environmentalism, and how to save the earth.

How did writing The Wildness Within shape your perspective of David Brower?

One of the things that came out of doing this book was how new this environmental movement is and how he was really in at the beginning of the modern movement. When he joined the as the executive director, he was only the second full-time employee. The first was secretary Virginia Ferguson. The result was that he had to do a little bit of everything, and he did a lot of things very well out of necessity. He was a filmmaker, he was a publisher of books, he was the editor of the Sierra Club Bulletin, he was a pamphleteer and lobbyist and a speaker. He did all those things pretty well, and I was impressed. I’d been there as a kid, but kids take these things for granted. Seeing it in a summary way was striking for me.

What was it like growing up with an environmental prophet for a father? Did you understand the importance of his work?

It grew on me slowly. I sort of knew he was important. But kids take what their parents do for granted. I just remember this episode where I was in the High Sierra with him, and a woman came to me on the way to the commissary in the mountains. She said, “Do you realize your father’s a great man?” She said it with a kind of irritation. And I didn’t realize that.

Was it natural for you to take on the faith of environmentalism?

It was. He was a very persuasive guy. He was always evangelizing for this movement. No audience was too small for him, even the kids at the dinner table. All our dinner table conversations turned to this subject. It was maddening in a way, but it was also exciting because it was a dinner table full of ideas and things that really were important. Everybody who came down the road, he drafted into the movement, including his own family.

You refer to your father’s campfire lectures as “The Sermon” and call environmentalism his religion. Who, for David Brower, is God, and who’s the Devil?

He wasn’t interested in evil or villains of his battles. He was never ad hominem with the personalities of his enemies. He confronted them on the issues. In fact, he grew very fond of some of his old enemies, like Floyd Dominy of the .

Who are the gods? He was very influenced by Howard Zahniser of the , who was as much as anyone his mentor. He was very good at finding the voices that supported his basic notion. Thoreau was there. was there, although he got tired of this Muir comparison. It was very common for the press to say he was the reincarnation of Muir, and he never expressed any enthusiasm for that.

Your father had a Theory of Everything approach to environmentalism. Can you explain what that means?

It arose out of those dinner table conversations. Within five minutes he would pirate any subject and see how it applied to environmentalism and conservation. It should have been very annoying because it implied a sort of narrowing of him. But the subject as he saw it was huge because everything funneled through it in his view of things. Almost anything that happens has implications for the health of the earth. So he became interested in nuclear and population and labor problems, immigration, and all kinds of things that in the ’50s were not considered proper subjects for environmentalism. But he continually broadened the focus. He pointed out again and again how much is tied up with this problem of saving the earth.

Do environmentalists still take that broad approach today?

It’s so easy to compartmentalize. There are people who do have the big view. Not enough with the kind of charisma he had. The movement, largely, has been corrupted by its own success. So many organizations are now run by MBAs as opposed to grassroots, fire-in-the-belly environmentalists, with lots of corporate types on the board. It was more simple and pure in the ’50s.

Your father believed in letting nature take its course. How important is that?

I was writing on that subject just an hour ago in another book I’m doing on the battle over the reservoir in Yosemite. There are various proposals on how to restore it. I’m very much in my father’s camp of hands-off [management]. Let’s see what the Tuolumne River does to restore Hetch Hetchy. Nature has had much more practice managing itself since the beginning of time. There are so many stories of how we’ve messed up in our hubris about how we can manage natural systems. It’s almost always a disaster. We’re seeing more and more hands-on, capital-intensive management of public lands, when I think nature does it better. This is one of the basic things we were taught as kids in those dinner table conversations.

What does modern environmentalism owe to David Brower?

I think there was a model of courage in the face of huge odds and huge forces arrayed against the movement. He was a man who didn’t compromise on his principles and did not hesitate to take on congressional forces and industrial forces that many people would have been hesitant to. There was a kind of bravery and hopefulness in the early years of this movement that still reverberates.

Publicly he had no qualms about engaging his opponents in environmental battles. Did he have any private turmoil, fear, or hopelessness about the fate of the earth?

In this conservation business, there are so many defeats, and they never knocked him off stride very much. I was always amazed at his resilience. Even getting kicked out of the Sierra Club, which he loved, only really delayed him for about a day. He was gardening and I asked him how he was doing. He said, “Not so good.” But by the end of the day he was okay and already started .

He may have had some private doubts, but he knew and often said that you can’t betray those, because then it’s all over. He really believed in the power of self-fulfilling prophecy. You have to make the good prophecies; the bad prophecies have a way of coming true.

He believed humor is as important to an environmentalist as it is to a stand-up comedian. Does that get better results than doomsday rhetoric?

He never was much of a doomsayer. The public gets so tired of that from environmentalists. Who wants to listen to the doom and gloom and apocalypse all the time? One of his one-liners was that the trouble with environmentalists and feminists is they don’t have any sense of humor. He always tried to keep it hopeful and funny if he could in “The Sermon.” You have to have an alternative for people. You have to show them an avenue to sanity.

Would David Brower be proud of how things have developed in the environmental movement today?

I think he would be unhappy about how much institutional inertia has developed in environmental organizations, how much emphasis there is on process instead of action. And he would not be happy with how things are going in the environment. One of his lines was, “All I’ve accomplished in my career is to slow the rate at which things get worse.” We have to come to terms with the fact that we are on a small planet, resources are finite, and we have to start living much lighter. It’s not happening. But he’d just roll up his sleeves and say we’ve got more to do. He’d be ready for the next round.