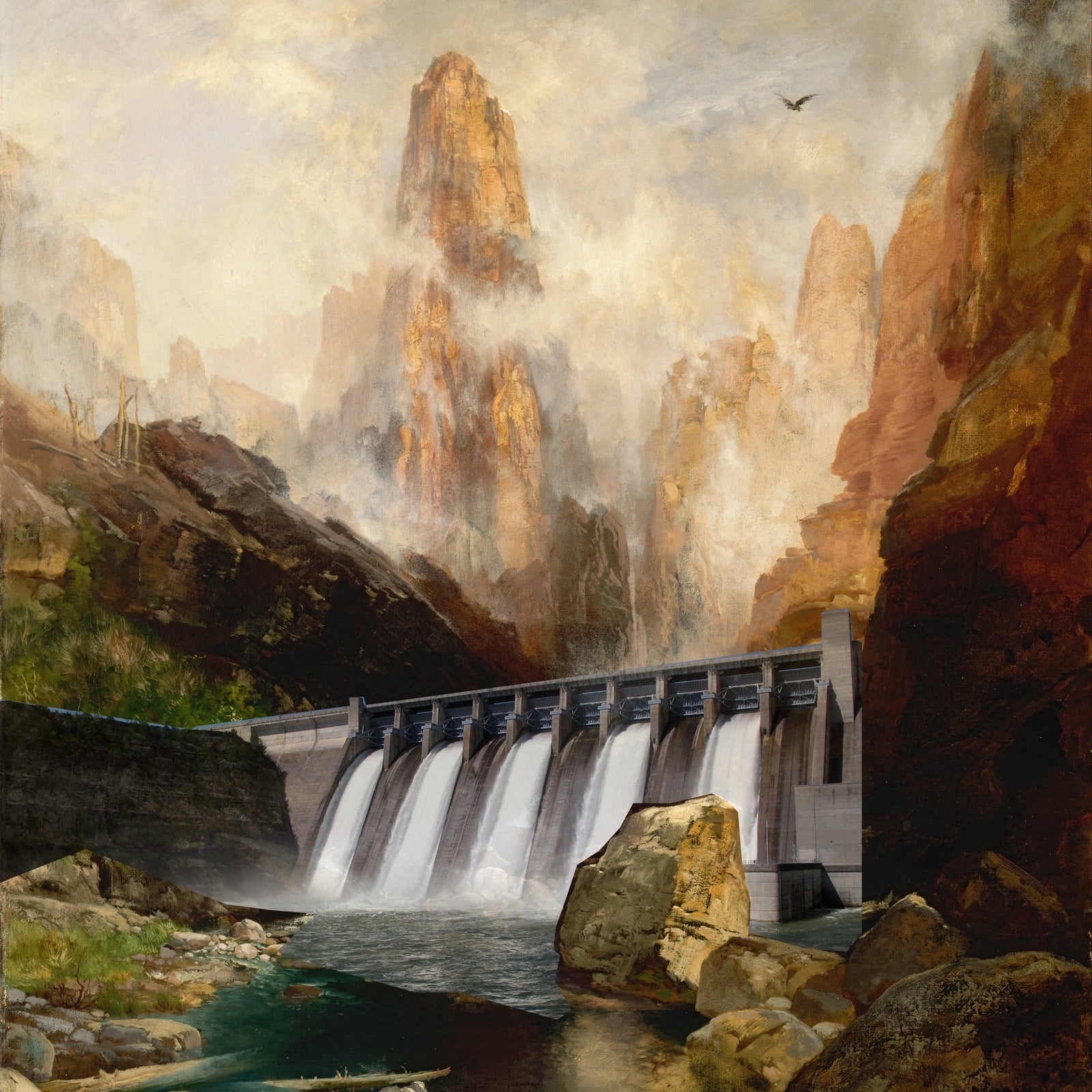

It takes a second to realize how disconcerting Will GurleyÔÇÖs painting of UtahÔÇÖs Kanab Canyon is, because itÔÇÖs so beautiful. The light hits towering spires╠řand then catches on a huge hydropower dam.

This painting is part of GurleyÔÇÖs series, in which he stylizes historic Hudson River School paintings, like Thomas MoranÔÇÖs dreamy canyons, and then twists them to show what those landscapes would look like through the lens of development,╠řlogged or sliced through by a highway. The╠řseries is part of a project he calls the╠ř,╠řwhich takes iconic American art about public lands, like those romantic╠řpaintings and the classic Works Progress Administration╠řnational-parks posters, and reimagines them to show what a human-chewed landscape would look like if we were to glorify it in the same way. He imagines YellowstoneÔÇÖs geysers converted into a water park and Zion pecked out into a series of apartment buildings. The paintings feel subversive, but they also donÔÇÖt feel that far off.

Gurley, who grew up climbing and mountaineering in Colorado, lives in Copenhagen now, where his day job is designing rides for the Tivoli Gardens amusement park. He recently closed a show for the National Parks Development project in Carbondale, Colorado, and now his New American Romantic series is available as a . He spoke to us about the line of preservation, how we commodify and glorify public lands, and the difference between being in nature and taking a picture of it.

On what feels important from far away: ÔÇťI created all this work over the past year from Copenhagen, so IÔÇÖm looking at the States from abroad╠řand thinking a lot about the American landscape. At the moment, these icons of America and our public lands feel like theyÔÇÖre really at risk. The national parks are landscapes that are dear to people, so I felt like it was appropriate to use them as my focus on attacks on nature. This project was also a way for me to reconnect with America╠řand Colorado. I grew up in Denver╠řand was a total outdoors guy, but as I got more and more involved with art and culture, I got sucked into the cities. I had this longing for the natural world, but now I was seeing them through kind of a tourist mentality.ÔÇŁ

On taking inspirationÔÇöand tweaking it: ÔÇťI have a passion for historical painting, especially landscapes. The representation of our landscape through history,╠řand how culture has looked at it, is really important. In a lot of the early paintings, the landscape has this storm that represents the uncontrollable aspects of nature, and a light beam across the landscape where humanity has touched it. ThereÔÇÖs a Manifest Destiny aspect╠řbut also beauty and awe of American wilderness. I really find that interesting. My paintings are supposed to be a critical stance against development of the outdoors, so I took that style and incorporated things like highway off-ramps that could easily happen.ÔÇŁ

On artists as conservationists: ÔÇťÔÇÖs most important paintings created ideas of protecting parks. He painted . They took this painting to Congress, because no one believed that it existed, but the painting was so convincing that Congress realized there was something to preserve. Artists helped make the national parks. They absorbed and reconfigured the narratives they decided to present about the American West.ÔÇŁ

On consuming nature: ÔÇťIÔÇÖm currently working on several paintings about views, and itÔÇÖs shocking╠řwhen I return to the States╠řhow much a view is an element of consumption. I was at Arches recently, and there were all these RVs and busses that arrived, people got out and took pictures, and then they left. People feel like theyÔÇÖre entitled to a view.ÔÇŁ

On how art can change your mind: ÔÇťI want people to approach it in an open way, so I make the work inviting, but then I have that hard-reality element within it. I have a small painting in my studio nowÔÇöitÔÇÖs a gorgeous ocean sunrise, with rocks out in the waterÔÇöbut when you get closer, you realize the water is bubbling up. The painting is called Slow Boil, and when you get near, the title reveals itself.ÔÇŁ

ÔÇťI donÔÇÖt mean to paint a grim picture of the world, but it is grim. Landscapes right now have a lot to be discussed, thereÔÇÖs a lot of sorrow. Books are one of the ways that IÔÇÖm communicating my work in the future. IÔÇÖm working on a childrenÔÇÖs book, or at least a book framed as a childrenÔÇÖs book, but with the harsh realities of humanity.ÔÇŁ

Other Climate Media WeÔÇÖre Checking Out This Month

ÔÇśThe Rosette,ÔÇÖ by Devon Galpin Clarke

What were you doing when you were 14? Probably not writing a graphic novel about species conservation and a shape-shifting hero fighting snow leopard extinction. WeÔÇÖre excited to keep our eyes on high-achieving world-schooled teen Devon Galpin ClarkeÔÇÖs book project, .

ÔÇśBroken GroundÔÇÖ

How many environmental disasters are slipping under the radar, especially when they happen in underserved, neglected areas? , a new podcast from the Southern Environmental Law Center, tries to find those cases. The first few episodes are about fatal coal-ash spills in the Southeast, and the details and scale of the problems are shocking.