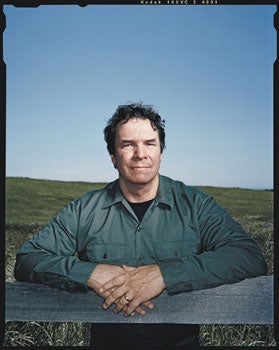

In November 2008, Greg Mortenson flew down to Santa Fe from his home in Boze┬şman, Montana, for a fundraiser that ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° had helped organize to benefit the Central Asia ┬şInstitute (CAI). The event took place in conjunction with our publication of ÔÇťNo Bachcheh Left Behind,ÔÇŁ a feature about Morten┬şson and CAI in that yearÔÇÖs December issue. I met him for the first time in the lobby of our offices, at around 11 in the morning on the day of the event. Mortenson had just finished a ┬şlocal radio interview, and ┬şafter we introduced ourselves, he gave an ┬şimpromptu presentation to our assembled staff about his recent school-building efforts in ┬şAfghanistan. After┬ş┬ş┬ş┬şward, I drove Mortenson to Santa Fe High School to speak to a group of students. I ┬şremember him scarfing down a sandwich in the back of my car, finishing just in time to hustle to our appointment.

His day was only starting. Mortenson spoke at two more local schools before dinner. I met him again at seven that evening at a large theater in downtown Santa Fe, where I intro┬şduced him to a sold-out crowd. He spoke for an hour, recounting his well-known story about getting lost after an attempt to climb K2 and wandering into the Pakistani village of Korphe, exhausted and alone. The locals had nursed him back to health, and in gratitude, he told the hushed crowd of nearly 1,000, he promised to return one day and build a school. The presentation ended with a standing ┬şovation, and Mortenson signed books in the lobby for another two hours. Most of the people in line had brought their own copies of Three Cups of Tea. When he was finished, only a few new editions had sold, which must have disappointed the owners of the ┬şlocal bookstore that had supplied the books for the signing. Sensing this, Mortenson bought the remaining copies. He asked that they be distributed to the local homeless shelter and nursing homes. Then, presumably, he went back to his hotel and went to bed.

All of that is true. All of it, that is, except for the details of MortensonÔÇÖs visit to ┬şKorphe and, perhaps, his motivation for buying those books. Ever since 60 Minutes aired its Mortenson expos├ę and Jon Krakauer published his exhaustive CAI takedown, ÔÇťThree Cups of Deceit,ÔÇŁ through Byliner.com, it seems like everything that took place on that day three years ago is in question. After all, those reports did more

than raise a few doubts about CAI and its founder. They bludgeoned Mortenson, documenting numerous false┬şhoods in Three Cups of Tea and outlining the disturbing use of CAI funds to promote his two bestselling books. The bookÔÇÖs fabrications were cited in a class action filed in May. The alleged misappropriation of funds, mean┬ş┬şwhile, is the subject of an ongoing inquiry of CAI by the Montana attorney generalÔÇÖs office.

The legal proceedings will take a long time to sort out. Until then, weÔÇÖre left with what appear to be two diametrically opposed narratives. We can continue to believe in the mission of CAI, excusing Mortenson as a charismatic visionary who, alas, is also a disorganized dreamer who was unequipped for CAIÔÇÖs meteoric rise. According to this narrative, he was brought down by a pair of mean-spirited journalists, one looking for TV ratings and the other for a big scoop to launch a new publishing venture. If we believe this version, the exhausting day I spent with Mortenson demonstrates his sincere and tireless effort to raise money for his cause and educate Americans about CAIÔÇÖs mission to build schools.

The other option: to believe that MortensonÔÇÖs entire body of work is a sham. He fabricated his visit to Korphe and embellished countless other details in Three Cups of TeaÔÇöabout his climbing r├ęsum├ę, about his kidnappingÔÇöbecause he knew the stories would help drive book sales. Those sales, in turn, created an ingenious feedback loop that bankrolled a perpetual donor-funded book tour that fed his ÔÇťinsatiable hunger for esteem,ÔÇŁ as Krakauer wrote. In this story, the day I spent with Mortenson was all about selling books and burnishing his image, not informing the public about the need for educating girls in the developing world. The fact that he bought the remaining copies of Three Cups of Tea at retail after the event is proof that he was manipulating bestseller lists and, assuming CAI paid for those copies, ┬şdiverting donations into his own pockets.

If it seems like IÔÇÖm distorting the two sides, visit our Facebook page or ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°online.com. Since we began covering this mess, weÔÇÖve received hundreds of comments, and nearly every one of them can be neatly placed into one of these two camps. So which is it? Is Mortenson a saint who must be protected from apostates or a sinner who must be brought to justice?

Given this magazineÔÇÖs long relationship with Mortenson, determining the answer hasnÔÇÖt been easy. Well before he was a philanthropic phenomenon, Mortenson served as an unofficial Central Asia fixer for ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° when we were reporting stories in the region heÔÇÖd come to know so well. In 2001, Mark Jenkins wrote a Hard Way column about MortensonÔÇÖs work, the first look at CAI in a national magazine and one of the first published accounts of his origin myth. Two years later, longtime ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° contributing editor Kevin Fedarko (the author of our 2008 Mortenson profile) wrote a story for Parade that put CAI on the map and yielded hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations. In other words, weÔÇÖre longtime believers in MortensonÔÇÖs mission. In 2009, I wrote a letter in this space about my plans to run a 50K to help raise money for CAI. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° readers donated more than $6,000.

All of these factors undoubtedly contributed to MortensonÔÇÖs decision to grant an exclusive interviewÔÇöapparently without telling his PR handlers or his lawyerÔÇöto ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° editorial director Alex Heard on the same weekend 60 Minutes dropped its bomb on CAI. And they most certainly ┬şcontributed to the impression many people hadÔÇöon both sides of the debateÔÇöthat ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° was defending Mortenson, no matter how probing our questions were. That opinion only hardened when we ran a follow-up story on our website about MortensonÔÇÖs K2 climbing partner Scott Darsney, who took issue with how heÔÇÖd been quoted in KrakauerÔÇÖs report.

The next day, we ran another story, ÔÇťCanÔÇÖt Get There from Here,ÔÇŁ which detailed our conclusion that MortensonÔÇÖs Korphe ┬şaccount was ÔÇťgeographically implausible.ÔÇŁ That was followed by a post examining CAIÔÇÖs donor newsletter, Journey of Hope, which had published a defense we found thin. ┬şGiven ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°ÔÇÖs long history with Krakauer, it was only natural that people now speculated that we were shilling for a contributor. Acting CAI director Anne Beyersdorfer forwarded us an e-mail from a supporter whoÔÇÖd written that she was canceling her subscription to ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° and implied that our close relationship with Krakauer was clouding our reporting.

The problem with that logic: we donÔÇÖt have a close relationship with Krakauer. While itÔÇÖs true that ÔÇťInto Thin AirÔÇŁ and ÔÇťInto the WildÔÇŁ are seminal pieces in the ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° canon, he hasnÔÇÖt written for the magazine in more than a decade. My only communication with him during the past five years has been through phone messages. I received the last one on the day we published the Darsney story. Krakauer was so incensed by the way we had edited Darsney's quote that he demanded his name be removed from our masthead.* (HeÔÇÖd been listed as an editor at large since 1998.) IÔÇÖve been a fan of KrakauerÔÇÖs writing since I was in college, but given how nasty he was to a colleague who was just doing his job ┬şreporting on Darsney, I was happy to grant his request. You wonÔÇÖt find his name on page 24.

So we seem to have found ourselves in that journalistic sweet spotÔÇöthe one where both sides hate our guts. Which is appropriate, since our instinct has been that the truth about Mortenson may lie in the middle ground between the two narratives. There is no doubt that he embellished and, at times, entirely fabricated parts of his creation myth. KrakauerÔÇÖs reporting on this is comprehensive, and Mortenson himself admitted to ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° that heÔÇÖd stretched the truth in Three Cups of Tea. How far? We still donÔÇÖt know. I was stung by MortensonÔÇÖs continued insistence in our interview that he had traveled to Korphe in 1993. IÔÇÖve been more troubled, however, by CAIÔÇÖs lack of transparency and the use of donations to advertise MortensonÔÇÖs books. These matters need to be fully addressed.

What IÔÇÖm not ready to buy is that Mortenson is a con artist who intentionally hoodwinked us all for profit. Krakauer quotes a former treasurer who says Mortenson used CAI as his ÔÇťpersonal ATM.ÔÇŁ And the class ┬şaction, which used ÔÇťThree Cups of ┬şDeceitÔÇŁ as its foundation, states that Mortenson made up his Korphe story as part of a grand plan to rook donors out of their money. (In 2006, after James FreyÔÇÖs memoir A Million Little Pieces was outed as a fabrication, his publisher, Random House, paid $2.4 million in legal fees and reimbursements to readers to settle a similar class action.) Intentionally or not, those accusations imply that Mortenson ┬şenriched himself with millionsÔÇöwe just need to follow the trail. The problem is, that trail leads us to these other things we know to be true. We know he still lives in a modest house in a middle-class neighborhood in Bozeman. We know he spent nearly a decade toiling in obscurity and scraping together tiny donations to build schools in Pakistan. We know he built dozens of those schools and that many of them, according to our own reporters who visited them on the ground, are a success. Mortenson is indeed a flawed individual with a troubling relationship with the truth, but the work he has done remains admirable and inspiring. And should he one day come clean about all the allegations, it would be tragic if he couldnÔÇÖt continue on with it.

Three Cups of Tea and “Three Cups of Deceit” both reveal something about their authors and the uncompromising beliefs that have fueled their incredible careers. One was written by a man who lied to promote a cause he believed in fervently, the other by a man who would stop at nothingÔÇöeven potentially wrecking an imperfect institution that nonetheless does noble workÔÇöto uncover the truth. I don't know how this battle will end, but here's hoping it leads to positive change rather than simple destruction.

* This sentence was changed from the following to more accurately reflect why Krakauer was angry about our reporting. “Krakauer was so incensed that we had dared to question his reporting that he demanded his name be removed from our masthead.” Click here to see the original Darsney piece and how we addressed Krakauer's complaint.