The podcast Ěýstarts with a murder. In 1999, angry about his wife’s roving eye, Patrick Dwayne Murphy, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, stabbed George Jacobs, another Creek, and left him to die on the side of the road.

The murder isn’t the complicated part—Murphy quickly confessed—but exactly where it happened is. Trying to avoid the death penalty, Murphy’s public defender, Lisa McCalmont, argued that the murder took place in Indian country, on the tribe’sĚýreservation, soĚýthe state didn’t even have jurisdiction to prosecute. The state argued that the reservation no longer exists, because it had already been broken up through allotment, a process of giving Native Americans U.S. citizenship if they signed individual land titles to separate where they lived from their tribe. In 2017, the TenthĚýCircuit Court ruled, saying that the reservation did exist, so the state couldn’t prosecute Murphy, but Oklahoma appealed. Now the case, Carpenter v. Murphy, is before the U.S.ĚýSupreme Court, which is supposed to issue a decision by the end of June. And that’s where things get really messy.

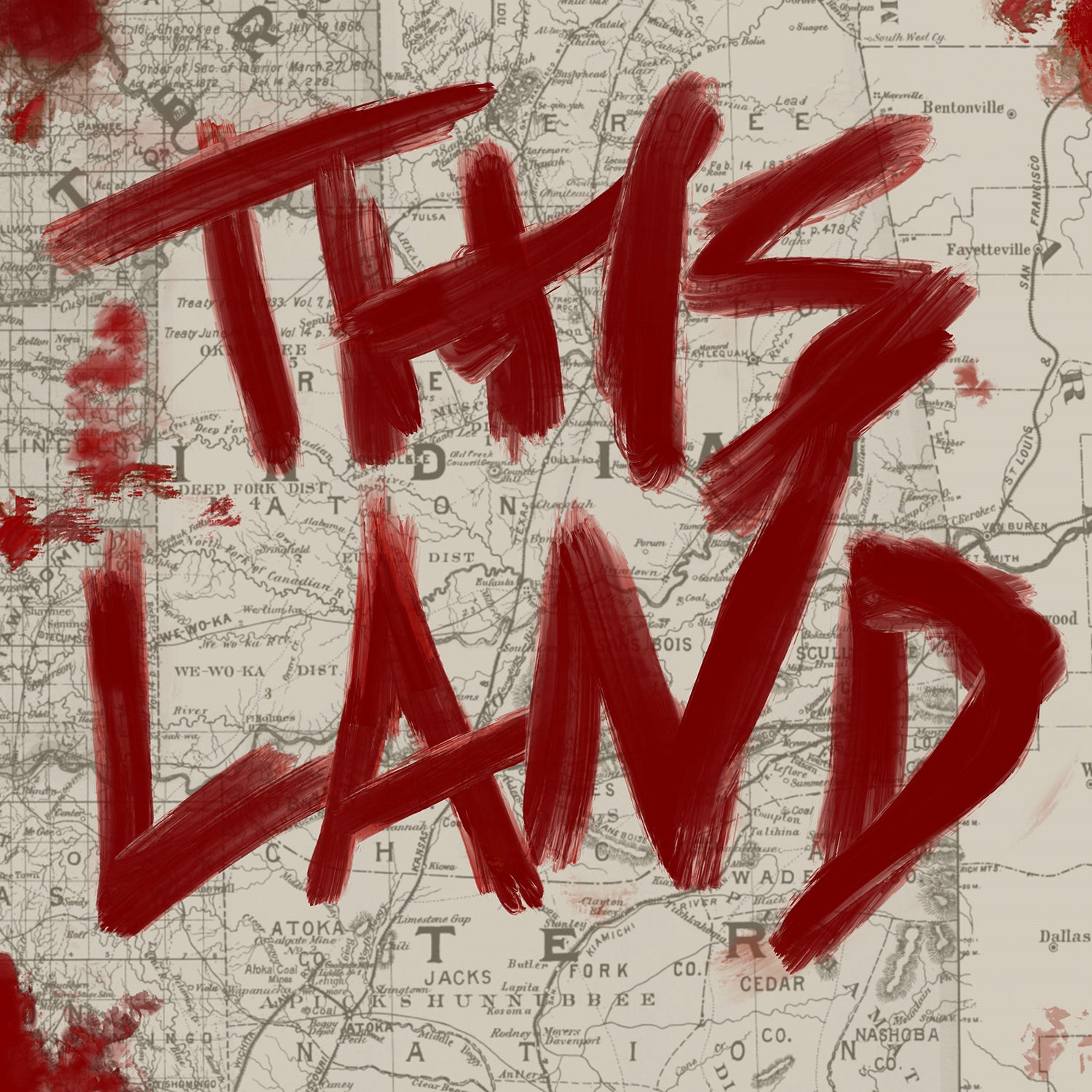

The case gets into a much deeper question about the tenacity of tribal land rights and who owns the land in Oklahoma, which encompasses 19 million acres of five tribal reservations, about half the state. If the decision goes in favor of the tribe, it could be the largest restoration of tribal land in U.S. history. In This Land,Ěýhost Rebecca Nagle, a journalist who covers tribal politics, digs into current policy and the backdoor ways that industries have been chipping at tribal sovereignty for decades. It’s a story that reveals a bigger picture of how tribes have been treated for all of U.S. history.

Nagle is an enrolled member of the Cherokee tribe—one of the five tribes in Oklahoma—and her ancestors, John and Major Ridge, signed the 1835 Treaty of New Echota that removed the Cherokee to a reservation in present-day Oklahoma in exchange for their ancestral land in the Southeast. She toldĚýşÚÁĎłÔąĎÍřĚýłŮłó˛ąłŮĚýthey thought the treaty was their best chance for survival, because of the ways tribes were being eradicated as white people claimed their land, even though many other tribal members were opposed. John Ridge was murdered by members of the tribe for signing the treaty, which ultimately wasn’t upheld. It cracked when Oklahoma became a state and the reservation was broken up through allotment, which is part of the state’s argument in Carpenter v. Murphy—that Indian country no longer exists.

Nagle says she’s worried that if Oklahoma wins this case it will set a dangerous precedent for how tribal sovereignty is upheld. The track record isn’t good. In the past 40 years, 117 cases about tribal law have gone in front of the Supreme Court, and only 12 have been ruled in favor of tribes. That’s the core of this podcast: to show how tribes have been marginalized and disrespected. Laws have bent to chip away at their rights when it’s convenient for states, the federal government, or lobbying interests like oil and gas. “Our sovereignty is boxed in through the creation of reservations,” she says, “but the U.S. doesn’t even respect that box.”

ThroughĚýa mix of interviews and narrative on the podcast, she interviews folks about the murder, steps back to look at case law and history, and digs into her own experience. “I am not telling the story of my family and my tribe to ask the Supreme Court to change the law. I tell this story to ask that the law be followed,” Nagle wrote in aĚý about the case’s initial oral argument, which spurred This Land.

Nagle says it’s hard to predict the Supreme Court case’s outcome. She says it’s likely the court will be split, which will uphold the sanctity of the reservationĚýbut doesn’t move the needle. Carpenter v. Murphy is part of a class of cases that cuts down tribes’ rights, like the recent Brackeen v. Zinke case, which challenges the Indian Child Welfare Act. “No tribe in the U.S. hasn’t had a piece of their sovereignty taken away because the government decided it could,” she says. “But it’s really about the types of arguments that people are using that are really dangerous. I want listeners to have enough information to know what they should be paying attention to.”