Editor’s note: While Roman Dial’s son’s full name was Cody Roman Dial, he also went by Roman.��In the below text, Roman��refers to Cody Roman, not his father.��

While Roman was exploring the cultures, mountains, and jungles of Central America, I was finishing up home projects and making short day trips and planning a long pack-rafting trip in the nearby Talkeetna Mountains in Alaska. I enjoyed hearing about Roman’s trips via email, but looked forward to having him home. When he’d written that he’d been bitten by a dog in Nicaragua and worried it had rabies, I’d even thought to ask him if maybe it was time to come back. But I didn’t.

It had been gratifying to me as his father to see him out on his own. He would return world-wise and confident with a broader view of life. His Spanish would be excellent. His view on economics��and the role of the United States in Latin America would be better informed. It was also clear that his adventures had grown naturally from his upbringing: our family trips to Australia, Borneo, Alaska’s wilderness, and elsewhere. I wanted to hear his stories, perspectives, and insights firsthand.

On July 14, home from a Talkeetna Mountains pack-rafting trip with my friend Gordy Vernon, I scanned Roman’s last email from Costa Rica:��“OK, I found what seems to be the best map yet.”��Unpacking and catching up, I read no further. But buried in the thread—unseen for another week—was his email that said he was “planning on doing 4 days in the jungle and a day to walk out.” We’d been emailing about “super-secret”��topo maps of Central America. The two threaded emails seemed part of that conversation. I didn’t read past “the best map yet.” If I had, then I would have known he planned to be out from his Corcovado trip the very next day.

July 15 was his out date.

The summer of 2014 was sunny in Anchorage and my wife��Peggy and I kept busy. We worked on house projects until peak salmon season, then drove to the Kenai Peninsula to dip-net fish for our freezer. We camped on the beach where the milky-blue Kenai River slides into the glacier-gray Cook Inlet and the sea breeze keeps July’s mosquitoes at bay. Beneath a clear sky and sunshine, we enjoyed the views of mountains rising above fishing boats plowing back to port, their holds full of freshly caught sockeye��salmon. The reds were running strong and people lined up shoulder to shoulder, standing in the river, their long-handled nets straining against the current as they excitedly pulled in fish when they felt a gentle bump in their net. We saw friends and filled our coolers with shiny sockeyes.

Still, it nagged at us that we hadn’t yet heard from Roman. I checked my phone for new emails as often as the spotty coverage on the Kenai allowed. Nothing. It had been six months since I’d seen him. He hadn’t told me exactly when he would be back from Latin America, but I hoped to have him home soon. I missed him.

Peggy and I returned from fishing on July 18, cleaned the 20��salmon we’d caught, and set to work finishing a siding project on our house. Days crept by. Still no word. We weren’t alarmed, just a bit surprised. Hardly a fortnight would pass since Veracruz (a��city in Mexico where he had traveled earlier in the year)��when we wouldn’t hear something from Roman. On July 21—12��days after he had last written—I sent a gentle reminder: “Let me know when you get out.” His email linked to the one starting with “the best map yet” sat unread in my inbox.

On July 23, Peggy and I wandered between fasteners and paint at Lowes, wondering aloud to each other why we had heard nothing from Roman. Two weeks had passed. The longest stretch he’d gone without contacting us after Veracruz had been ten days, during his trips across El Petén and La Moskitia, wild regions in Guatemala and Honduras, respectively, where he had traveled in between Veracruz and��Costa Rica. We were worried now.

“I need to look at his last email again,” I told Peggy. “I didn’t really read it carefully and I’m not sure what he wrote. It seems like it was just about maps.”

Then and there in Lowes Home Improvement, Peggy felt nauseous. We left empty-handed to drive straight home and read his emails carefully. I opened the July 9 thread where the words��“heading in off-trail tomorrow . . . 4 days in the jungle and a day to walk out” spilled across my screen. My face went numb.��

Oh��no! He’s way overdue—fuck!

I should have been paying closer attention!

Shock washed over me. Then guilt. Guilt over the fact that I hadn’t read his email thoroughly, that I hadn’t given him the attention he deserved. That, maybe, like Peggy pointed out in nearly every argument, I spent too much time on my own trips, on my own interests.

“Peggy. This email says he should have been done, like”—I struggled with the arithmetic—“like, ten days ago! Something’s wrong!” I turned to her. Her forehead tightened, cheeks slack. She saw my terror; it increased her own.

We jumped into action. She slid me a notebook and pen across the table, then got on the phone and called our daughter��Jazz. I set to work on the computer, my hands shaking. Fighting panic and rising nausea, I Googled Corcovado National Park guides, looking for someone to help us.

My Spanish too poor to call, I shot off an email to Osa Corcovado Tours.

My name is Roman Dial and my son, Cody Roman Dial, age 27, is missing in Corcovado National Park. He is about 177 cm tall (5 feet 10 inches), with blue eyes, brown hair and glasses. He weighs about 63 kg (140 lbs). He should have a blue two-person tent.

He has been traveling for several months in Central America and doing treks in the jungle, always without a guide.

He emailed us on 9 July and said that he was heading into Corcovado National Park on 10 July for five days alone. He should have returned ten days ago, and he always reports back to us. But we have heard nothing and now are worried.

He wrote that he would be hiking off-trail to the east of the Los Patos to��Sirena Trail. He said he’d be walking about 5 km a day for 20 km off trail, following the Rio Conte up, then crossing the mountains over to the Rio Claro and follow��that to the coast.

Again he said he would be gone for 5 days and that was almost 14 days ago. Can you please advise me what I can do or how we might look for him? I do not speak Spanish, but perhaps I could call someone and speak on the phone? Attached is a photo from two years ago.

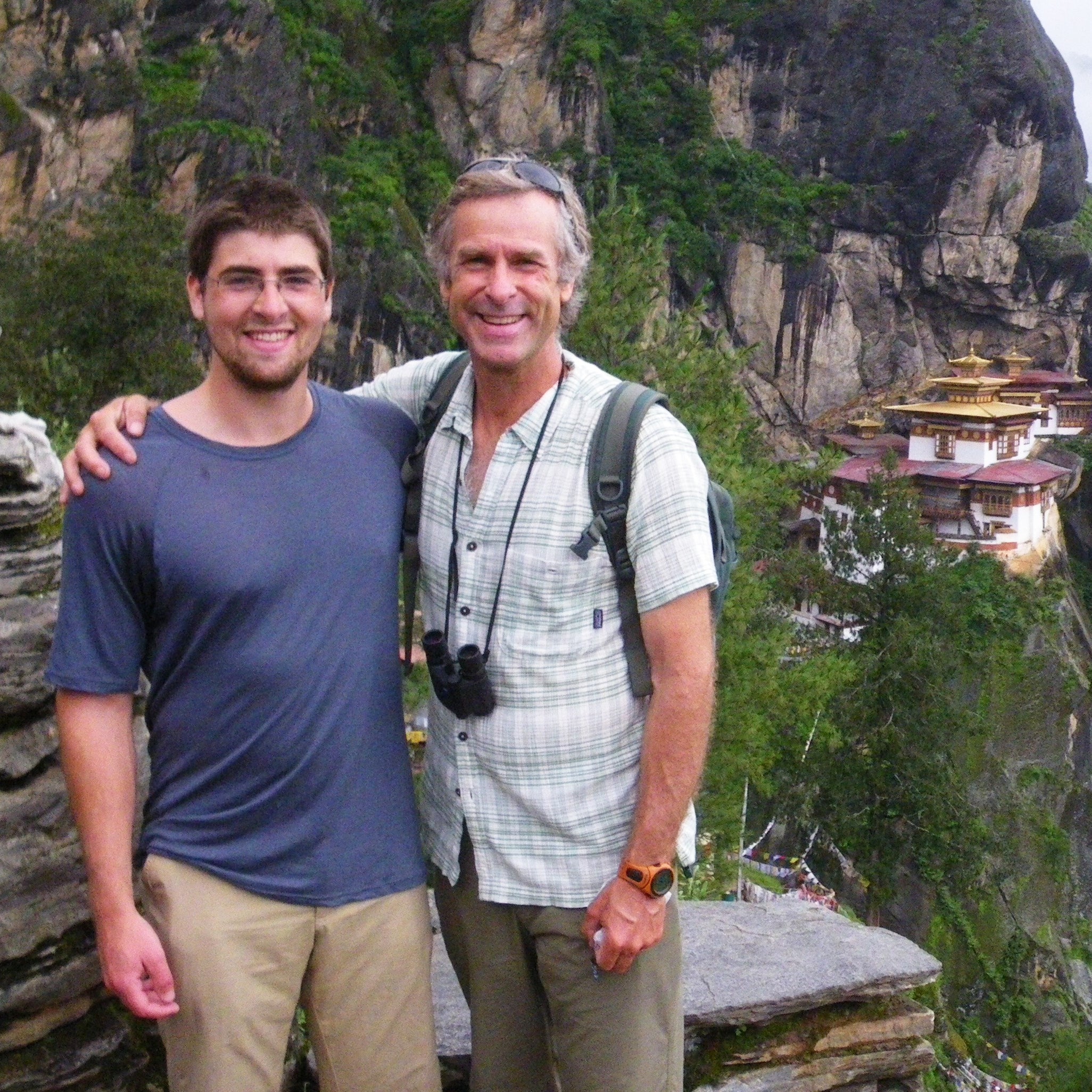

The first picture of Roman I found was from Bhutan. Smiling at the camera, he’s a little pudgy, with a bit of beard, short hair, and wire-rimmed glasses, wearing a blue shirt. My arm is around him, hand on his shoulder. I attached the photo and “the best map yet”��and hit send.

I bought an airplane ticket to leave the next day for Costa Rica. I could not stay in Alaska. I would not leave the search up to others. He was my son. My responsibility was to him. Part of the Alaskan creed is that we take care of our own. I had been on enough rescues to know our system worked. Roman had sent me his plans and a map because he knew that if something happened to him, I would come get him.

I had introduced him to the tropics, to wilderness, to world travel. No one knew better what Roman might do. But I needed experienced, reliable help we could trust. I called Gordy. A world traveler himself, he once lost six fingertips when he quit his own attempt at the summit of Mount Everest to rescue another climber on the mountain. He had also lost his father and two siblings in a tragic airplane accident.

Gordy went silent for a minute when I told him the news. He’d been on the Grand Canyon trip with Roman and me. He appreciated Roman’s toughness, wit, and modesty.

Gordy’s voice was slow and measured, fighting back emotion. “Nah, Roman, my Spanish just isn’t good enough for something like that. You’ll be better off with Thai.” Thai Verzone, his Wilderness Classic partner and protégé, had been both a Latin American studies major in college and a mountain guide in Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia. He speaks Spanish fluently.

Gordy went on. “You know, what I would do is get hold of Roman’s bank records. Those might say a lot about where he was, and where he was going.” This advice from a close friend helped. Peggy would try over the coming days, but it took years in the end to get the records.

I called Thai. “Thai‚ Roman’s missing in Costa Rica.”��

“W��?”

“Yeah, he wrote he’d be gone on a five-day trip in Corcovado, but he’s like ten days overdue!”

“Oh shit—ten days!”

“Listen, can you go down there with me? I need you. I’m leaving tomorrow and could really use your Spanish and jungle skills.”

Thai’s wife, Ana, had just had their baby, Maia, three months before. Thai helped Ana at home and worked at the hospital.

Peggy knew how useful Thai would be with language, wilderness, and people. She quickly volunteered: “I can watch Maia for Ana while Thai goes with you.”

I relayed this to Thai. “Peggy says she can help Ana with Maia if you can come.”

A recording said, “Push two for life and death.” I pushed two.

“Let me check with Ana and the clinic, but I’m pretty sure I can do it. How long will we go for?” Thai had his own life.

“If you could come down for ten days, that’d be great. Thai, I really need your help.”

Panic inched up my gorge. I choked it down. Calmness thinks clearly.��

I was terrified that Roman, lost and broken in the jungle, waited for me to come get him. Hadn’t he given me very explicit directions and a map, after all?��

I called the U.S. embassy in San José, worried it might be closed. A recording said, “Push two for life and death.”

I pushed two. A voice answered and said something about a duty officer, then gave me a Mr. Zagursky’s email. I scribbled it in my notebook, then emailed the photo, map, and information to him. I found an email address for the Puerto Jiménez police and sent them the same content, adding Gordy’s suggestion to access Roman’s bank records. I told them all that I was coming down.

My body crawled with anxiety and a sense of panic held barely at bay. I wanted to be down there right now. Every minute counted. While the tropics might seem hot and idyllic, the rains are cold and the chance of rapid infection is real.

I called my boss at work: “Roman’s missing.”

Her response was immediate, empathetic. “Oh, Roman,” she said genuinely, “I am so sorry.” As if he were already dead, that I’d already lost him.

Hurt and angry, I told her, “I’m going down to find him and am not sure when I’ll be back.” What I meant was that he wasn’t dead, that she didn’t need to be sorry because I would bring him home alive.

That evening��I packed jungle gear. Shoes and shirts and pants and a pack. Compass and headlamp. Stove and a cook pot. Dehydrated food. Bug-net tent and tarp. Sleeping pad and sheet. We would have to move fast. Bring only necessities.

My feelings of shock ebbed, exposing a reef of guilt. He’d written that he’d be out on the 15th. I was home then. I should have read his email.��

I should have given him 24��hours, then called Costa Rica on the 16th��to say he was 24��hours overdue, then flown there on the 17th. I could have done that.��

But I didn’t. A full week had passed since I could have flown down. It was impossible not to see him suffering, waiting, wondering, Dad, where are you? I told you where I went. I said I’d be out in five days. Dad, come get me!

Hoping for the best, I emailed him: “i am coming down to look for you.”��The subject read “email please!”

My flight left for Atlanta at 8:30 at night on Thursday, July 24. All day I switched from phone to computer, scrambling to put things together. My brain struggled to function as if nothing were wrong while my heart wrested to take control and panic. Peggy, too, called and emailed friends and family, sounding the alarm. Within 24��hours, friends set up a fund and deposited money for our search.

The Tico Times, a Costa Rican English-language newspaper, . People reached out to help. Then��Facebook kicked in. Someone posted on an Osa-specific page about a sighting. I messaged him and he wrote back:

I am 90% sure that I saw your son based on his picture—did he have a tan safari type outfit (shorts and shirt matching and a hat)? I remember seeing him walking alone along the road and I took him for one of the many volunteers who are always in that area and who never want a ride. I made eye contact with him and he nodded. He was looking into the woods at something that caught his attention. If you want you can call. Hopefully he is simply walking through some tough terrain out in the park and working his way back.

I ached for it to be true. But it couldn’t be Roman dressed in safari garb, turning down a ride on a road. I knew that it wasn’t. Together we had spent too many months over too many years in too many countries on too many continents for that to be the son I raised.

He was in trouble. I knew.

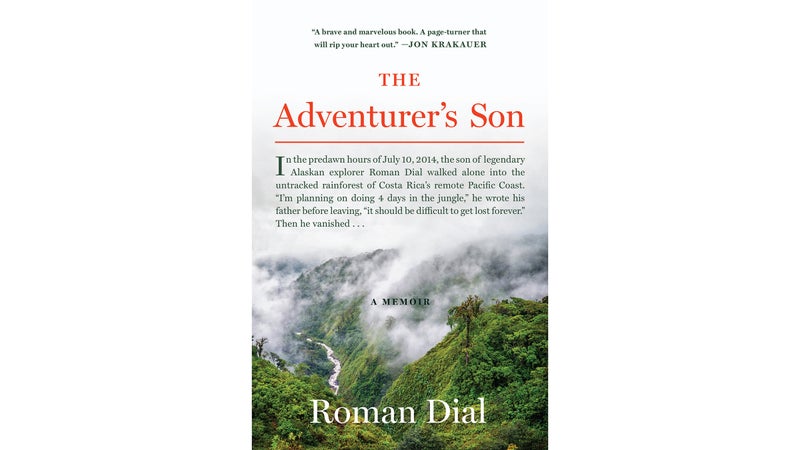

From the forthcoming book . Copyright © 2020 by Roman Dial. To be published on February 18, 2020, by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Find�����ϳԹ���’s past��coverage of Cody Roman Dial’s 2014��disappearance here��and��here.