Montezuma’s funerary mask. A cheating blue-blood fiancé. A meth-addicted grave robber. A country of primary colors and corruption. And a protagonist whose internal conflicts are in stark contrast to the face she shows the world.

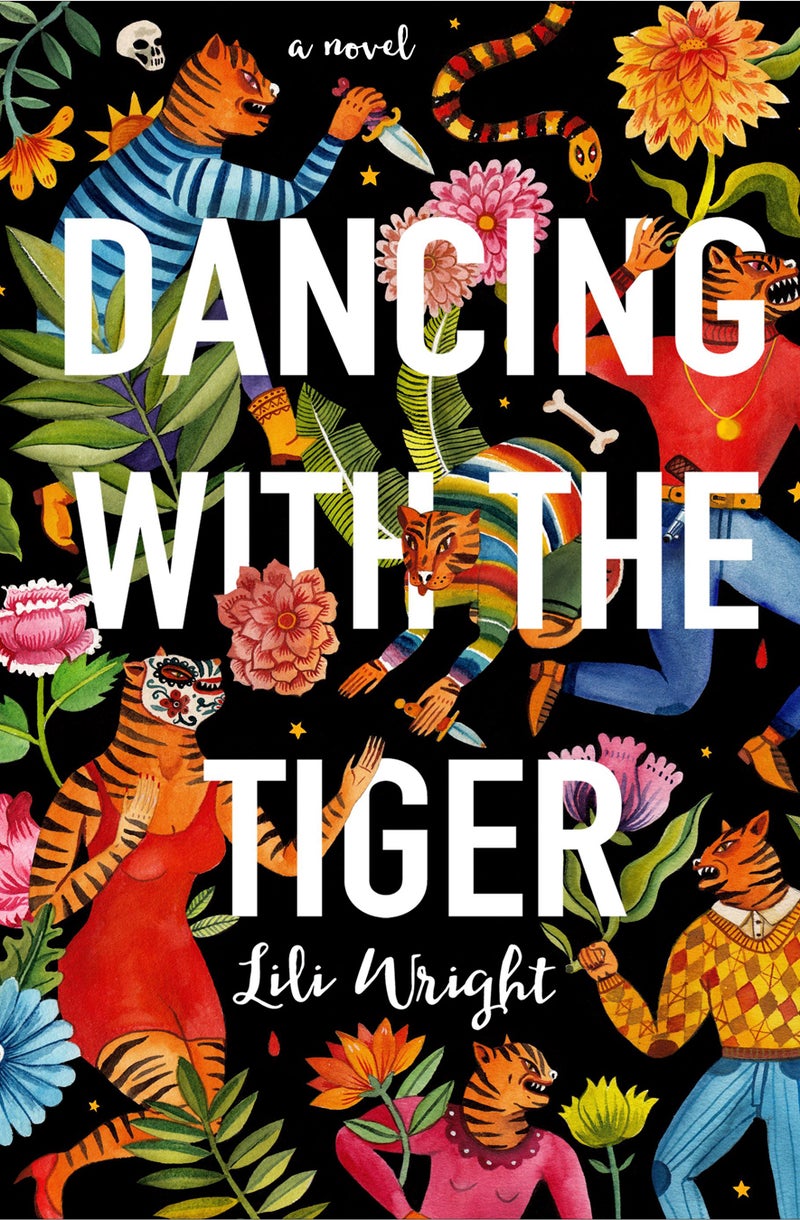

This is just the beginning of memoirist Lili Wright’s debut novel ($26, Marian Wood Books/Putnam). The fast-paced, 450-page literary thriller combines mystical realism with reporter-solid revelations about Mexico’s drug war and the issue of relic repatriation in the art world. Set largely in Oaxaca, Mexico, it’s an immersive exploration of place and cultural veneration of the sacred object.

The story has a shape-shifting, restless quality to it. It’s told from multiple points of view (“Ann,” “The Looter” “The Gardener;” “The Housekeeper”), and in short (often one-word) sentences. Wright’s scenes are constructed with care, full of sensory descriptors, blunt dialogue, and surprising verbs (“fidgeting a crossword;” “stabbing a walking stick;” “tobacco fingers twinkling”). Threaded through each is the Mexican backdrop, captured in high detail and arguably better developed than any of the characters.

In this way, Wright is similar to her character The Looter, whom we see in the prologue frantically cleaving the earth in search of the one-eyed Aztec mask around which the story will revolve. Wright, too, is obsessed with peeling back our layers of self-imposed protection, with exposing the details in the overlooked cracks of the world.

When we first meet the heroine, Anna Ramsey, she is leaving her art-dealer fiancé and her curated New York City life behind, bound for Mexico. She means to acquire the Aztec mask for her father, a disgraced, alcoholic art collector still mourning the death of Anna’s mother 20 years before. Anna, a fact-checker (an odd profession for a protagonist, but, one assumes, an insight into her character as a truth-seeker), is the nexus of the story. Around her, the other characters loom, fading in and out of focus, hidden and revealed in turn.

At times, however, it seems as though Wright is grasping for command over her considerable stable of characters, that their exploits are upending her control. As the momentum builds so does the violence, which becomes almost sensational, while the romance between Anna and Salvador feels canned. Toward the end, the mask changes hands like a hot potato, and Wright doesn’t orchestrate its trajectory enough to allow the reader to keep up. The plot, while ambitious, becomes increasingly chaotic as it progresses.

Given the intricacies of the storyline, Wright takes writing liberties that don’t always work in her favor: a grin is never just a grin, it is a “wolfy grin.” A sleeping man is curled “into a comma, a messy hunk of punctuation.” An addict’s insides are “a toilet of acid.” On one occasion, the air smelled of cinnamon and dust; on another, raw meat. At best, this over-writing is distracting. At worst, it will make the reader long for simple, unembellished narration.

However, out of the litany of lines that reach and fail, there is the occasional sentence good enough to redeem the rest. If readers stick with this book, it’ll be because of imagery like this: “He turned the corner. Threw the fucking cup against a wall. The juice dripped down the stucco, a new sun exploding.”