The sinking of the SS El Faro, on October 1, 2015, was America’s worst maritime disaster in decades. El Faro was 790 feet long and hauling 25 million pounds of cargo from Jacksonville, Florida, to San Juan, Puerto Rico. About halfway through its voyage, the ship ran into Hurricane Joaquin’s 130 mile per hour winds and 40-foot waves. None of the ship’s 33 crew members survived.

El Faro slowly became a rich subject for writers. The National Transportation Safety Board’s investigation of the sinking turned up thousands of documents, and there were weeks of public hearings trying to figure out what went wrong. Most important, there were 26 hours of audio straight from El Faro’s bridge, preserved on a black box and retrieved from the wreckage nearly three miles underwater by a robot submarine.

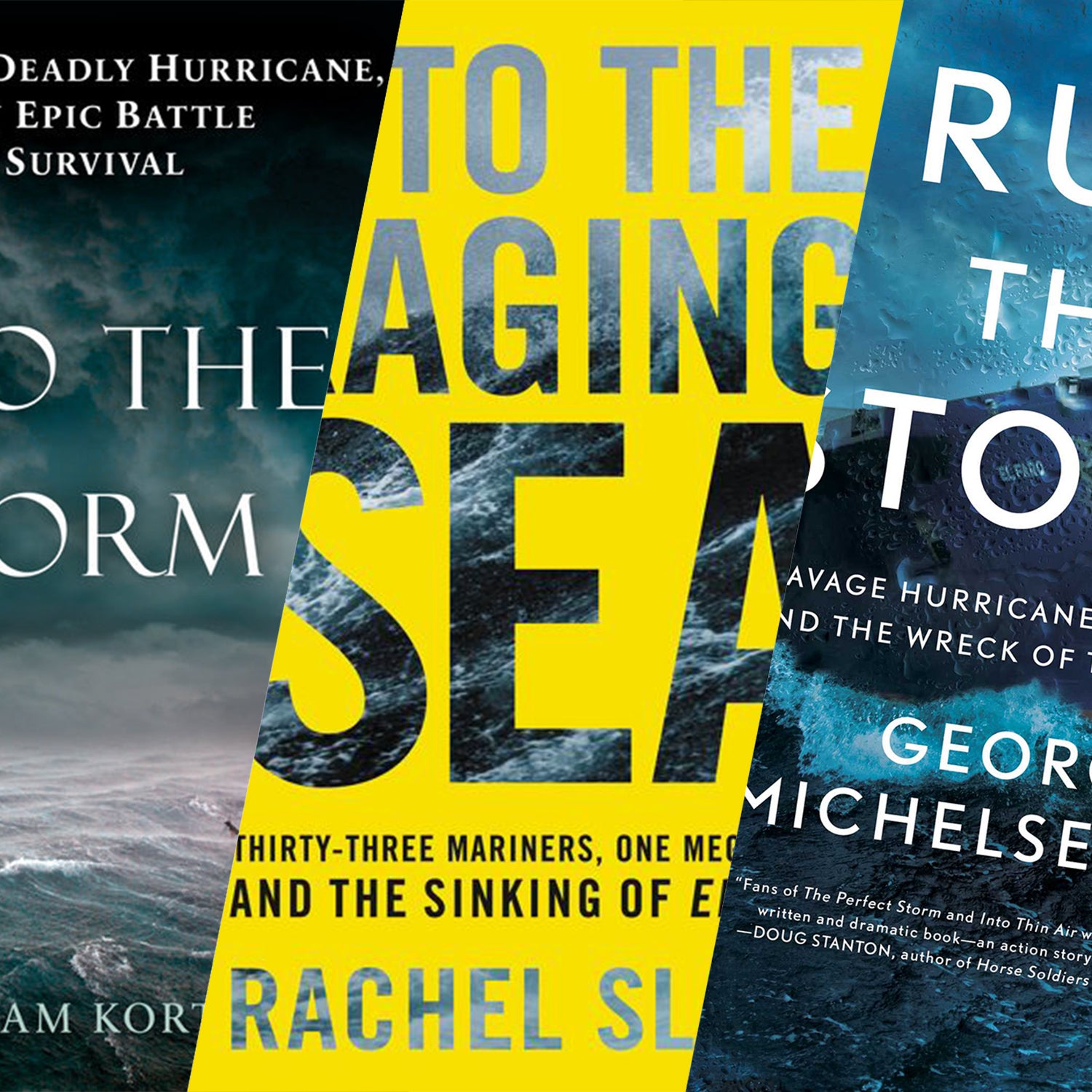

When El Faro’s two defining traits come together—the tragedy and the archive—they create an incredible true story of nautical disaster, of real human beings facing things the rest of us can’t imagine. So it makes sense that, this spring, New York publishers are releasing three different nonfiction books on the ship. The books’ titles make for a morbid Venn diagram of overlapping words: There’s Boston-based journalist Rachel Slade’s , Miami-based journalist Tristram Korten’s , and New York–based author George Michelsen Foy’s . Thankfully, all three avoid sensationalism and offer serious looks at the sinking, though one does emerge as the most insightful exploration of this unthinkable disaster.

When people think of them at all, most of us think of cargo ships like El Faro as indestructible. They are so big, so federally regulated, so fortified by modern technologies of navigation and weather forecasting. How could this happen in 21st-century America?

For a lot of reasons, it turns out—most of them small. When El Faro left Jacksonville on September 29, captain Michael Davidson knew about the coming storm. He had a good reputation in his industry. (“A by-the-book mariner,” William Langewiesche called him in a recent .) But Davidson also seemed to be angling for a promotion, and he didn’t want to annoy his bosses at TOTE Maritime Inc. by asking for more time and fuel. The bridge microphones caught him reassuring his crew: “You can’t run [from] every single weather pattern.” So the ship followed its normal route with only minor deviations, even as it moved closer and closer to the storm.

That storm kept growing stronger, eventually becoming a Category 4 hurricane. But a software glitch left El Faro’s officers with weather data that was hours old; the ship’s anemometer had broken weeks before, which meant they couldn’t tell how fast the winds were blowing. A few people on the bridge tried to convince Davidson to change course, but they didn’t try hard enough, or he didn’t listen hard enough—as in any workplace, it’s difficult to know the histories behind a decision. “I think he’s just trying to play it down because he realizes we shouldn’t have come this way,” said Danielle Randolph, the second mate, when the captain wasn’t on the bridge. “Saving face.”

The bridge audio abounds with moments like that, simultaneously humanizing and heartbreaking. When Davidson finally decided to ring TOTE’s emergency call center, he got stuck in the sort of loop you’d expect if you were calling about problems with your cable box. (What’s your best callback number? Can you explain the problem again?) Even near the end, El Faro’s crew seemed more shocked than terrified. When Randolph finally saw the storm on the horizon, all she said was, “There’s our weather.”

The end, when it came, came quickly. The waves and wind became too much even for a ship the size of El Faro. It began to list severely, taking on water until it lost its engines, until the cars in its hold were bobbing around themselves. The ship continued to tilt and started to sink; Davidson gave the order to abandon ship, but in the middle of a hurricane, lifeboats and immersion suits were useless. The air was so saturated with rain and spray that it would have been as impossible to breath above the water as below it.

All three books capture the tragedy and suspense of El Faro. The timing might make this seem like a ghoulish scramble, something the publishing industry has certainly managed before. (A deadly 1998 yacht race in Sydney, Australia, also produced .) But each El Faro volume finds a unique angle, even if their titles all sound the same. Slade spends the most time with the crew’s families and their persistent grief. Korten broadens the narrative to include the M/V Minouche, a smaller ship hit by Joaquin, and the Coast Guard’s attempts to rescue the crews of both.

Foy does the best job. He tells the story briskly and confidently while working in helpful asides: how cargo containers are fastened to a ship deck, how forecasts are determined, how huge ships stay upright (and how they don’t). Run the Storm is too dense in a few spots, especially in its footnotes, but it gracefully covers everything you’d want to know about El Faro’s sinking and the 33 lives that went with it.

Still, the most moving parts in all three books come from those recordings. Take the end of the tape, right before the audio cuts out—when Davidson and his helmsman, Frank Hamm, were the only ones left on the dramatically slanted bridge, with the ship’s alarms ringing in the background, with their voices rising into screams. All three authors have the good sense to basically quote it verbatim:

Hamm: “My feet are slipping. I’m going down.”

Davidson: “You’re not going down.”

Hamm: “I need a ladder.”

Davidson: “We don’t have a ladder. I don’t have a line.”

Hamm: “You’re gonna leave me.”

Davidson: “I’m not leaving you. Let’s go.”

Hamm: “I need someone to help me.”

Davidson: “I’m the only one here.”

Hamm: “I can’t. I can’t. I’m a goner.”

Davidson: “No, you’re not.”

Hamm: “Just help me.”

Davidson: “Frank, let’s go. It’s time to come this way.”

At the end of Moby-Dick, after Ahab and his ship have vanished, Melville describes the ocean enduring: “Then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled 5,000 years ago.” The sea still rolls, but one thing that’s changed is the technology that records it. This technology isn’t perfect—software still hiccups, anemometers still break—but El Faro’s black box has commemorated the crew in a way nothing else could. The lines remain so powerful because they are freighted with the knowledge that the speaker will soon be dead.